Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Friday, 21 April 2023 00:20 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

As Minister of Finance, Mangala was among the few in Sri Lanka who took the fiscal deficit seriously, acted on it, and was maligned for his efforts

Raghuram Rajan became famous for predicting the 2007-08 crisis and its causes two years earlier. He warned of a looming “catastrophic meltdown” in financial markets thanks to “housing prices that are at elevated levels around the globe. While the techniques and instruments to absorb fluctuations have improved, there is uncertainty about how they will perform in a serious downturn.”

Raghuram Rajan became famous for predicting the 2007-08 crisis and its causes two years earlier. He warned of a looming “catastrophic meltdown” in financial markets thanks to “housing prices that are at elevated levels around the globe. While the techniques and instruments to absorb fluctuations have improved, there is uncertainty about how they will perform in a serious downturn.”

Who was our Raghuram Rajan? I always mention Indrajit Coomaraswamy’s carefully worded and oft repeated cautions. But he was not alone, and he did not use terms such as bankruptcy, which Central Bank Governors cannot use. Mangala Samaraweera, then Minister of Finance, was a lot more colourful in his response to the election manifesto of Gotabaya Rajapaksa. He called a press conference and sent out this memorable tweet in October 2019:

“Gota’s tax plan wants to set #SriLanka on an Express Train to bankruptcy, default and a Greek style debt-crisis. VAT change alone equivalent to Health, Defence or Pensions budgets. #LKA certainly doesn’t need advice from a PR agency conjured ‘business community’.”

This alone justifies a look back at Mangala’s performance as Finance Minister, in the context of the crisis that came as predicted, and the steps being taken to recover and prevent recurrence.

Fiscal deficit

It’s said that there’s an alternative meaning to the acronym IMF: “It’s Mostly Fiscal.” As Minister of Finance, Mangala was among the few in Sri Lanka who took the fiscal deficit seriously, acted on it, and was maligned for his efforts.

There are two ways to narrow fiscal deficits: Increase revenue; decrease expenditures. Or do both, ideally.

The Government has four sources of revenue: taxes; non-tax revenue (charges for various services such as passports, visits to wildlife sanctuaries, etc.); grants; and loans. Grants are few and far between. In all of 2022, Government received Rs. 10 billion in grants (0.48% of total revenues that year). Non-tax revenues were Rs. 232 billion in 2022, after many charges were increased in mid-2022. That was just 12.5% of the total. So, tax revenue is what matters.

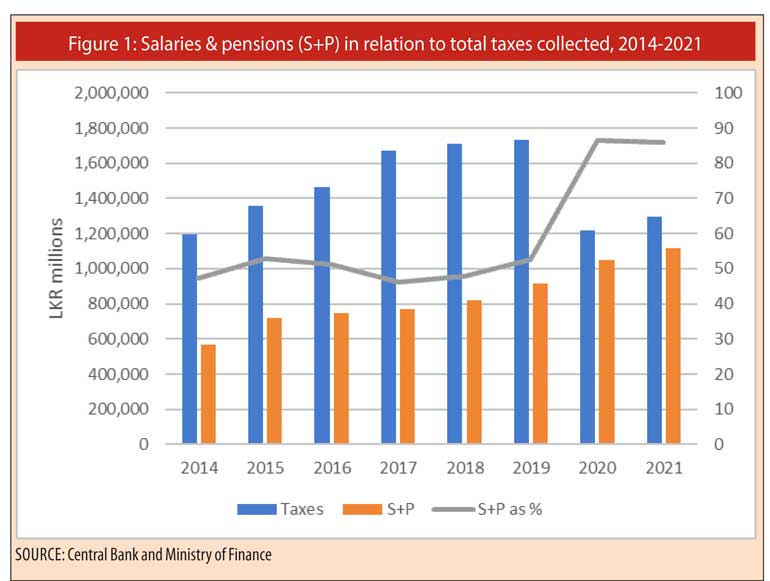

On the expenditure side, the State spends on many things. But by focusing on the biggest items of salaries and pensions, which would cause conniptions if unpaid, we can get a sense of how much is available for other things such as funding state hospitals, welfare benefits. If there isn’t enough, government must borrow. As we now know, bad consequences such as galloping inflation and bankruptcy follow when borrowing is excessive.

2021, salaries and pensions ate up 86% of total tax revenues. In those two years, all other government expenditures had to be covered by the less than Rs. 200 billion in tax revenues that remained, a similar sum from non-tax revenues, grants, and borrowings. In 2017, by comparison, Rs. 900 billion of tax revenues remained after paying salaries and pensions.

Disbursements for salaries and pensions increased in single digits throughout, except for a 26% jump in 2015, a 15% increase in 2020, and an 11% increase in 2019. They spike in years with presidential elections, followed by general elections. In such years, the party that wins the presidency gives away public funds to buy votes in the general election. For example, in 2015, all state employees were granted Rs. 10,000/month allowance, and Mahapola payments were increased.

The biggest sinner was the finance minister of the minority UNF Cabinet formed in 2015, Ravi Karunanayake. In the gap between Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s November 2019 victory and the general election, the usual happened. The salaries and pensions bill spiked by 15%. In addition, taxes were slashed. Viyath Maga luminaries such as Nalaka Godahewa wanted high growth at any cost, and blamed Mangala’s tax reforms for slowing growth. The unprecedented reduction in tax revenues from Rs. 1,735 billion in 2019 to Rs. 1,217 billion in 2020 was a result. It led to ratings being lowered, which then triggered the crisis.

Mangala was not blameless on the expenditure side, as can be seen from the 11% increase in what was spent on salaries and pensions in 2019, a presidential election year. And it must be noted that he also contributed to the mindless expansion of those in state employment over the years.

What he deserves praise for is higher tax revenues in 2017-19. Like the present Government, Mangala sought to achieve a primary surplus through a revenue-based fiscal consolidation. The internal dynamics of the government that existed in 2017-19 permitted little else. He did not come near the primary surplus target of 2.3% given in the IMF program. The IMF team is talking about Mangala’s consecutive surpluses in the quotation below.

“Historically, Sri Lanka has only had a primary surplus on three occasions, and never for more than two years; and fiscal consolidation efforts in Sri Lanka’s past IMF-supported programs were quickly reversed after the program. The size of the programmed fiscal adjustment is unprecedented for Sri Lanka, but necessary given that it started with one of the lowest revenue-to-GDP ratios in the world after previous fiscal reforms were undone. For example, large real cuts to public sector wages and public pension payments amid high inflation in 2022 could prompt a backlash against the program from current and retired civil servants.”

Current account deficit

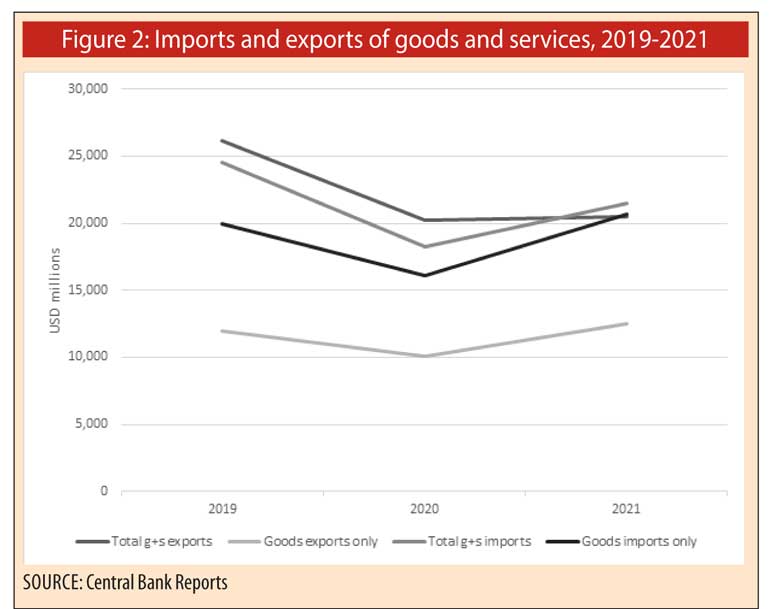

The underlying disease that was aggravated by the Viyath Maga tax cuts of 2019 and sent the patient into the ICU was known: the twin deficits that Sri Lanka suffered from throughout the post-independence period. The fiscal deficit was the one that Mangala tackled head on. The second deficit is the current account deficit, which is caused by importing more than what we export year after year. Most people talk only about the export and import of goods, but we should talk about both goods and services as are shown in Figure 2.

In 2019, the year before the return of the Rajapaksas, the $ 19.9 billion spent on merchandise (goods) imports could not be covered by what was earned from the export of goods, $ 11.9 billion. But with earnings from service exports (including worker remittances resulting from Mode 4 Service Exports), goods and services imports could be covered. In 2020, goods exports declined to $ 10 billion because of lockdowns and resulting damage to supply chains. The decline in service exports, in tourism in particular, was even worse. But because imports declined sharply, things were still manageable. By 2021, total goods and services exports were inadequate to cover even goods imports. Everyone knows how that played out in the second half of 2021 and 2022.

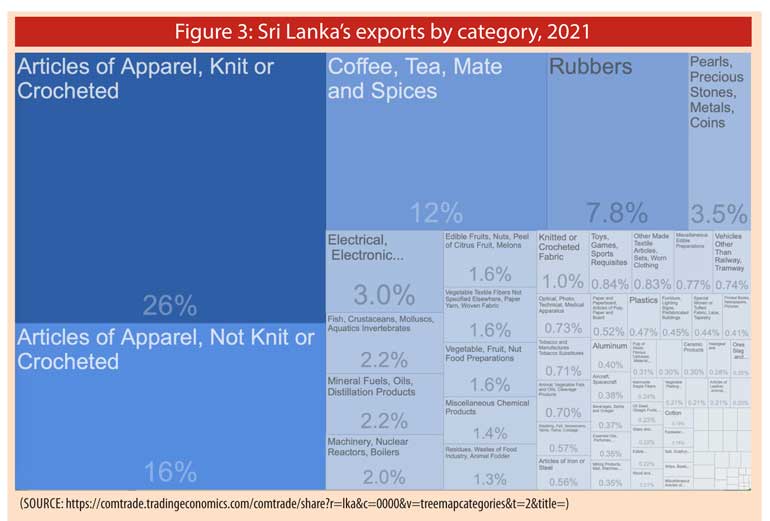

Very clearly, we must increase exports, not only of goods but also of services. Our goods exports are not diversified, not high value, and go to a limited number of countries.

Just three items, apparel, tea, and rubber products, make up 63% of all export earnings. We must diversify not only what we export but also the markets. The primary export destinations are the United States and Europe. We must reduce that reliance and sell more to Asia.

Mangala is unlikely to have had a big impact on promoting goods exports, as Minister of Finance (getting GSP+ back was a major achievement, but that was as Minister of Foreign Affairs). On the services side, Enterprise Sri Lanka tried to help small-scale suppliers of tourism services, by actions such as facilitating the issuance of wine and beer licenses. The key actor in export promotion is the Export Development Board (EDB), which was not under the Ministry of Finance. It is implementing a national export strategy under the guidance of exporters (much can be improved in the EDB’s performance). He could have phased out para tariffs that make it difficult for Sri Lankan firms to participate in global production networks. This has been announced, again, in the 2023 Budget Speech.

Eliminating the fiscal deficit is a necessary condition for recovering from the crisis and preventing a relapse. But it is not sufficient. For that, a whole-of-government approach to making the economy more efficient by opening the economy to domestic and international competition is required. Removing protectionist barriers, improving the ease of doing business, helping enterprises to gain market access through partnership with foreign investors and through trade agreements are some of these measures.

Outside electoral politics

When Mangala declined to run in the 2020 general election, he said he was done with electoral politics. But not with politics. The period from that announcement to his demise in 2021 was devoted to the development of a youth-centric movement, anchored on his belief that the next phase of Sri Lankan politics was going to be defined by the young and powered by social media. As he predicted the crisis, he also predicted the Aragalaya that toppled the people and the policies responsible for the crisis.

Despite his somewhat unusual predictive abilities, Mangala was no deity. He made his share of mistakes. There is no reason to ask “what would Mangala do.” Only MPs can serve in the Cabinet. So, there is little value in speculating what portfolio he could have served in, etc. That would be contrary to his stated position that what is required now is a new kind of politics.

The remedial actions included in the IMF program and beyond it are those that were defeated in the past when proposed. There is a freeze on state employment and moves to end non-contributory pensions in 2002. That government lost the subsequent election. Efforts to restructure SOEs and enter into trade agreements have repeatedly failed. But these are now underway. Serious labour law reforms have never been tried. But even that is on the cards now.

Patron-client culture and years of propaganda inculcating false patriotism have combined to stymie reform. But now, as seen from the lack of public support for trade unions fighting to safeguard their privileges, conditions have changed. If effective execution of reforms by those within government is combined with coordinated and powerful messaging by those outside government, reforms may have a chance. This appears to be the course of action that logically arises from what can be inferred from Mangala’s vision of a new kind of politics.