Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Monday, 13 January 2020 08:58 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Prof. Ajantha Dharmasiri

I was very pleased to deliver my first-ever convocation address at the recently concluded convocation of the Wayamba University of Sri Lanka. In today’s column I have produced the entire text of my speech.

Honourable Chancellor, Vice Chancellor, distinguished academics, respected invitees, my dear graduands, it gives me immense pleasure to be with you all on this solemn and significant occasion. I consider convocation as a commencement in consolidating competence and confidence. A new journey has just begun. Hence, at the outset, let me congratulate all graduands who have gathered here, for their gallant path ahead.

I intend to share a few thoughts on management, as a learner. I believe in lifelong learning and encourage all of you to continue to be learners.

Overview

Any management textbook will give the definition of modern management as “a set of activities, including planning and decision-making, organising, leading and controlling directed at an organisation’s human, financial, physical and information resources, with the aim of achieving organisational goals in an efficient and effective manner”.

In a crude sense, management can be broken into three parts - man, age and ment. It essentially speaks about people, times and actions. As Mintzberg (1971) advocated, successful management involves interpersonal, informational and decisional roles.

Any organisation can be viewed as a system, comprising inputs, throughputs and outputs. Hence, management can also be defined as human action, including design, to facilitate the production of useful outcomes from a system. This view opens the opportunity to ‘manage’ oneself, a prerequisite to attempting to manage others.

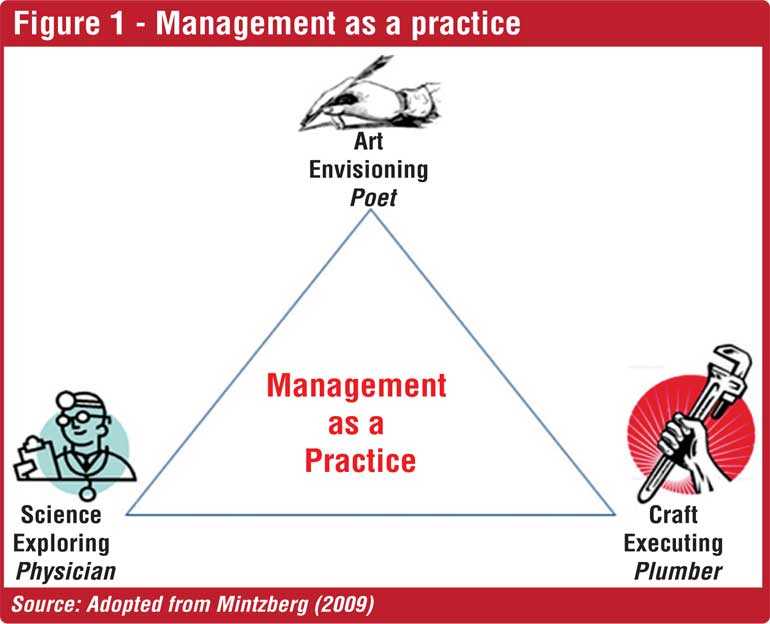

In a typical workplace, managers have a vital role to play. Mintzberg (2009) highlighted management as a practice involving art, science and craft. I attempted to reflect more on this and to elaborate further. Figure 1 contains the details.

It is interesting to identify a manager as a poet, physician and a plumber, to use three simple metaphors. He or she has to engage in envisioning, exploring and executing. As a poet, a manager shall create a vision for the future, in displaying his or her leadership qualities. As a physician, he or she can analyse, diagnose, resolve and do many other tasks in exploring a scenario. As a plumber, he or she can attend to operational issues that need immediate attention, in fixing things and in executing.

How can we produce managers as those playing triple roles as poets, physicians and plumbers? This is where management development comes to the forefront. It is not merely an academic activity nor practical skill building. It requires a holistic approach in enhancing the knowledge, skills and attitude of managers. The graduands gathered here have to be geared to this glaring reality.

Mindset at the forefront

I see having the right mindset as the prime need for such an endeavour. As the first stanza of the revered Buddhist text the Dhammapada states: “Mano pubbaagma dhamma, mano seta manomaya”. This essentially means that the mind is the forerunner for all things.

While its supremacy has always been undisputedly accepted, just what exactly the mind is has been a perennial question. Philosophers strived to describe it while psychologists struggled to define it. As one relatively simpler definition states, the mind is the human consciousness that originates in the brain and is manifested especially in thought, perception, emotion, will, memory and imagination (www.phychologytoday.com). Psychologists such as Sigmund Freud and William James have developed influential theories about the nature of the human mind. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the field of cognitive science emerged and developed many varied approaches to the description of the mind and its related phenomena.

In Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of personality, the conscious mind consists of everything inside of our awareness (www.boundless.com). This is the aspect of our mental processing that we can think and talk about in a rational way. The conscious mind includes such things as the sensations, perceptions, memories, feelings and fantasies inside of our current awareness.

Mind and the brain

Though the vital connection between mind and brain is obvious, how they are really linked is yet to be comprehensively understood.

“Because our consciousness notices everything, it observes and pays attention to us. It is aware of our thoughts, our dreams, our behaviours and our desires. It ‘observes’ everything into physical form,” said Joe Dispenza (2007), who is a neuroscientist with a biochemistry background.

In his book, ‘Evolve Your Brain: The Science of Changing Your Mind’, he connects the subjects of thought and consciousness with the brain, the mind and the body. The book explores ‘the biology of change’. That is, when we truly change our mind, there is physical evidence of change in the brain.

As we are aware, the brain is the most complex organ in the human body. The way New Scientist magazine describes it, it produces our every thought, action, memory, feeling and experience of the world. This jelly-like mass of tissue, weighing around 1.4 kilograms, contains a staggering one hundred billion nerve cells or neurons. The brain is suspended in cerebrospinal fluid, effectively floating in liquid that acts as both a cushion to physical impact and a barrier to infections.

The complexity of the connectivity between these cells is mindboggling. Each neuron can make contact with thousands or even tens of thousands of others, via tiny structures called synapses. Our brains form a million new connections for every second of our lives. The pattern and strength of the connections is constantly changing and no two brains are alike.

In neuroscience, we have three brains that allow us to go from thinking to doing to being. The ‘thinking brain’ is the neocortex, the ‘doing brain’ is the limbic brain and the ‘being brain’ is the cerebellum.

“Every time we learn something new, we forge a new synaptic connection in our thinking brain,” says Dispenza (2007).

The neocortex is that corrugated brain that sits on the outside, allowing us to gain information from our environment. So when we begin to learn new things, we add a new stitch to circuits that represent the three-dimensional tapestry in our grey matter.

As he further explains: “Now it’s not enough to just learn that information. It’s important for us to apply what we learn, to personalise it, to demonstrate it. We have to take what we learned intellectually or philosophically, the knowledge that we’ve gained, and apply it, personalise it, demonstrate it and change something about ourselves. And when we do, we have a new experience.” (Dispneza, 2007)

How do we activate the second brain called the limbic brain? Experience enriches the brain because when in the midst of a new experience, everything we’re seeing and smelling and tasting and feeling and hearing, all of our five senses, are gathering all this information from the environment and it’s sending a rush of information back to the brain through the five different pathways, causing jungles of neurons to organise themselves to reflect the event. These neurons begin to represent the environment and produce chemicals that begin to signal the body. That’s how the limbic brain or the “emotional brain” works.

As Dispenza elaborates, “The moment we begin to modify our behaviour and we have a new experience, now we are instructing the body emotionally to teach it what it has intellectually understood. Having got two brains working together by now, we have mind and body in unison. It is not enough to have the experience once, but should be able to repeat it, do it over and over again, with memorising. Dispenza calls this “neurochemical conditioning” your mind and body to the point where your body knows as well as your brain.

What comes next is the state of being. That is when our thoughts and feelings are aligned to a concept and we activate that certain brain called the cerebellum, the memory centre in which we’ve practised it so many times, we no longer have to think about it. According to Dispenza, “The process of change requires us to go from thinking to doing to being”.

Our hardwired thoughts, our habitual behaviours and our memorised emotions determine who we are. And the quantum field tends to respond to who we are. Not so much our desires or what we want, but who we’re being. So moving into a state of being then allows us to change not only our health, but avenues and venues in our lives.

From clutter to clarity

Let me connect mind to matter. It reminds me of the popular Japanese approach called the ‘Five S’ system. Better housekeeping, higher orderliness and enhanced productivity are some of its described benefits. It is no stranger to the Asian workplace. According to the Asian Productivity Association (APO), the origin of this productivity technique can be traced back to heavy steel industries in Japan more than 30 years ago (www.apo-tokyo.org).

The ‘Five S’ stands for the five Japanese words that start with the letter ‘S’: Seiri, Seiton, Seiso, Seiketsu and Shitsuke. An equivalent set of ‘Five S’ words in English have likewise been adopted by many, to preserve the ‘Five S’ acronym in English usage. These are Sort, Set, Shine, Standardise and Sustain. The Five S offers a systematic approach in keeping things in order. It is a visual technique of ensuring proper housekeeping as well. As Hirano and Talbort (1995) state in the ‘Five Pillars of the Visual Workplace’, Five S forms the bedrock for productivity. Further, Osada, (1995) highlights in ‘The Fiv5S’s: Five keys to a Total Quality Environment’, it offers a pathway for quality and productivity improvements.

Dear graduands, you may wonder why I attempt to connect abstract concepts with applied chores. Why does the mind need the Five S? This has been a question in my mind for a while. Removing clutter from the workplace is fine but more clutter remains in the mind, in the forms of negative emotions, inaccurate perceptions and false opinions. Even though the Five S has been successfully implemented in many Asian workplaces, the depth it contains in making the participants disciplined has not been adequately captured (Dharmasiri, 2019).

I assume this is vital for new graduate entrants to the modern day workforce like you.

Seiri (Sort) is the starting point.

Typical workplace activities include going through all tools, materials and so forth in the plant and work area. Keeping only essential items and eliminating what is not required, prioritising things according to their requirements and keeping them in easily accessible places are other key actions. Everything else is stored or discarded.

The way I see it, the deep relevance of Seiri to the mind is purposefulness. In order to ensure clarity over clutter with ‘right seeing’ (Samma Dhitti in Pali), one needs to identify positive thoughts, constructive emotions and unbiased perceptions with a clear purpose in mind. It resonates with what Covey (1989) called, “begin with the end in mind”. This is much more difficult than sorting things in a workplace.

Seiton (Set) typically means arranging workplace equipment, parts and instructions in such a way that the work flows free of waste through value-added tasks with the division of labour necessary to meet demand. It follows the practice of “everything has a proper place”. It is all about efficiency.

As I observe, the deep relevance of Seiton to the mind is prioritising. It requires focusing on value creation. Connecting thoughts in a logical manner with proper analysis is the need. It in fact helps oneself to focus on tasks linked to targets in the context of overall purpose. What is connected to the purpose has to be a priority. The rest has to be “set aside” to be done only when time permits. Covey et al (1995) highlighted this aspect connected to time in their seminal book, ‘First Things First’.

Seiso (Shine) involves cleaning the workspace and all equipment, and keeping them organised. In a typical factory, at the end of each shift, clean the work area and be sure everything is restored to its place. This step ensures that the workstation is ready for the next user and that order is sustained. As Japanese advocate, cleaning must be done by everyone in the organisation, from the directors to the drivers. Everyone should see the workplace through the eyes of a visitor - always thinking if it is clean enough to make a good impression.

The way I see it, the deep relevance of Seiso to the mind is purity. This is where the spiritual dimension looms large. Pure thoughts devoid of malice, jealously and other negativities are what are required. A shining mind is a spiritual mind empathising with others compassionately. Zohar (2012) emphasised this dimension in her trend-setting book, ‘Spiritual Intelligence: The Ultimate Intelligence’.

Seiketsu (Sustain) is all about uniformity and consistency. In a typical workplace, uniform procedures need to be ensured throughout an operation to promote interchangeability. It can also be viewed as “conformance to consistent clean-up”.

It consists of defining the standards by which people must measure and maintain ‘cleanliness’. Seiketsu encompasses both people and environmental cleanliness. Personal tidiness can be a good starting point.

I think the deep relevance of Seiketsu to the mind is perseverance. So many start-ups might end up half way through without proper completion. A mind that is geared towards perseverance will ensure continuity of a recommended habit, preferred value or a best practice. One needs determination and dedication in order to sustain noteworthy initiatives.

Frankl (1985) highlighted the need to have perseverance, in sharing his Jewish concentration camp experiences through his ground-breaking contribution, ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’.

Shitsuke (Standardise) refers to ensuring the disciplined adherence to the previous four Ss. It assists in preventing a possible backslide to where thing were prior to the implementation of the Five S. The key word here is discipline. It denotes practising Five S as a way of life. As the Japanese say, the emphasis of Shitsuke is the elimination of bad habits and constant practise of good ones. Once true Shitsuke is achieved, people will do things naturally, without reminders and warnings. The way I see it, the deep relevance of Shitsuke to the mind is pro-activeness. Gardner (2006) captures the essence of such an approach in his insightful contribution ‘Five Minds for the Future’. With a proactive mind, purposeful, prioritised and pure actions can be continued with perseverance. In essence, it sums up the overall application of Five S to the mind.

Road ahead

Dear graduants, as we saw clearly so far, mind, matter and managers have a coherent connection. You will be absorbed into different types of workplaces. You will be climbing the managerial ladder as a poet, physician and plumber. You will be using mind before action for multiple results. Remember to commit towards continuous learning.

As the Buddha said: “What we are today comes from our thoughts of yesterday, and our present thoughts build our life of tomorrow. Our life is the creation of our mind.”

I wholeheartedly wish all graduands gathered here a glorious future. May you go, grow and glow.

(Prof. Ajantha Dharmasiri can be reached at [email protected], [email protected] or www.ajanthadharmasiri.info)