Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 2 November 2019 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

To start with, let us briefly review some of the important landmarks in the history of Muslim community in this country since it set foot in the eighth century.

To start with, let us briefly review some of the important landmarks in the history of Muslim community in this country since it set foot in the eighth century.

For more than a millennium and until the beginning of the 20th century, Muslims enjoyed a unique and exemplary period of peaceful coexistence and prosperous living that is incomparable with any other Muslim minority anywhere in the world.

In this regard, this community is indebted to the boundless hospitality and benevolence extended to them by the Buddhist monarchs of this blessed island. Even when the community faced repression under the Portuguese it was a Buddhist monarch who provided asylum to Muslim refugees.

That era of peaceful coexistence and relative prosperity received a hiccup in 1915 under British rule, when riots broke out between Sinhalese and Muslims, primarily because of the uneven distribution of economic opportunities and benefits arising from a laissez faire plantation economy. There were also other reasons, which, for the sake of brevity can be skipped for the moment. However, the bitterness provoked by these riots between the two communities evaporated soon and relations went back to normal until the country became independent in 1948.

From mid-1950s, another chapter opened in the political history of this country, which once again brought the two communities even closer. Unfortunately, this closeness took place at the expense of a larger minority, Tamils, that decided to distance itself from coalescing with the Sinhalese, and chose to engage in a political struggle which was to cost them dearly as that struggle proceeded and became violent.

In a sense, given the ethno-democratic politics of independent Sri Lanka, the post-1950s closeness between Muslims and Sinhalese was more a politically motivated pragmatic alliance of convenience than a marriage out of love. However opportunistic that closeness was, it endured, in spite of occasional bubbles, until very recently and benefitted the Muslim community in many ways.

The year 2009, which closed, perhaps for ever, the separatist aspirations of the Tamil community, also brought into question, from a group of ultra-nationalistic Buddhist Sinhalese, the usefulness and relevance of an alliance of convenience with Muslims. Actually, that year marked an epochal transformation in the relative political configuration of all three communities.

To the Sinhalese Buddhists, the absolute annihilation of the Tamil militia promised the ultimate realisation of a long-cherished dream to Buddhisise Sri Lanka. The ultra-nationalist Buddhists coalesced and emerged into a supremacist movement intending to transform political Buddhism into a domineering hegemonic force.

To Tamils, it was a time for serious self-introspection about where they went wrong in the past, and how they should re-design their future to live with dignity and honour and without losing their proud cultural heritage. And, to Muslims the year 2009 marked the beginning of a new era of turbulence not only in their relationship with both Sinhalese and Tamils, but also within themselves.

It is in such a tumultuous political atmosphere that all three communities are called upon to elect a new president in a few days and a new government later. Although the issues facing the minorities have been discussed in general previously (see, ‘Political Buddhism, Presidential Race & Minorities,’ Colombo Telegraph, 25 October and Daily FT 28 October) the following discussion is focused entirely on Muslims.

Muslims in a real quandary

Muslims are in a real quandary. Their current situation is a self-inflicted wound started pestering because of past neglect. In the early decades after independence, when Muslim political leaders enjoyed a period of honeymoon with their Sinhalese counterparts, and were able to win several favours from the governments, benefiting both themselves privately and their community publicly, many of them had little idea as to how their community was going to change in the future. Because of lack of foresight, Muslim leaders in general took little notice of some of the religious and social undercurrents in the community, which were to turn cataclysmic as the century moved into its last quarter.

I have alluded to these undercurrents in several of my previous contributions to this journal (see for example, ‘From the Safest to an Insecure Sri Lanka for Muslims,’ Colombo Telegraph, 6, 9 and 14 March 2018), and need no repetition now. It was these undercurrents that ultimately produced Zahran and his National Tawheed Jamaat of terrorists, which killed hundreds of innocent Christian worshippers on that fateful Easter Sunday.

Having failed to detect the currents on time and take appropriate counter measures to navigate the community along safe waters, it is of no use now for Muslim leaders to plead innocence for what happened in April. One may even go a step further and accuse Muslim leadership for worsening the situation by taking political advantage of those undercurrents. (Whether the Easter tragedy could have been prevented or not is not relevant for this discussion.)

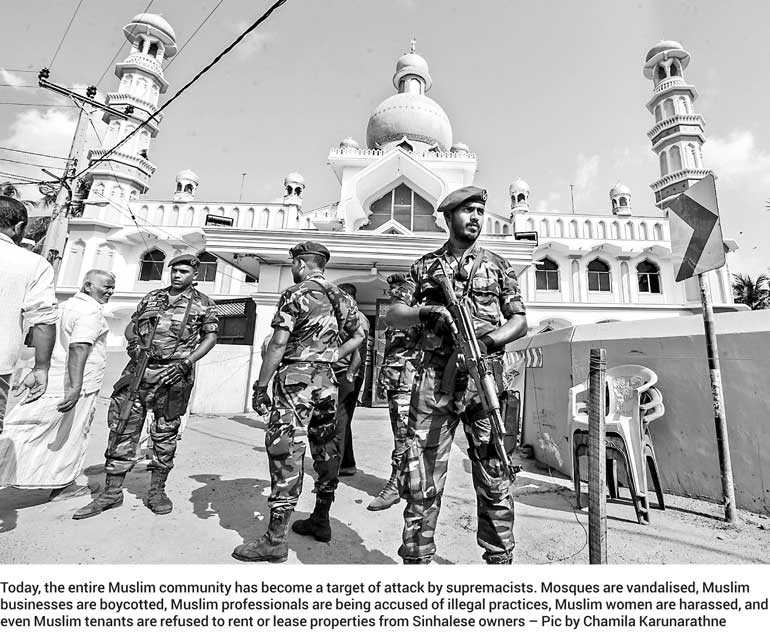

Entire community under attack

Today, the entire community has become a target of attack by supremacists. Mosques are vandalised, Muslim businesses are boycotted, Muslim professionals are being accused of illegal practices, Muslim women are harassed, and even Muslim tenants are refused to rent or lease properties from Sinhalese owners.

More seriously, Muslims have been pronounced as aliens after living here for more than a millennium. Neither the President, nor the Prime Minister and nor the Leader of Opposition has condemned this outrage and said anything so far to mitigate the sorrows of Muslims. It appears that all of them are prepared to grant impunity to supremacist miscreants and would even encourage them to carry on with their anti-Muslim operations, if those operations were to benefit the leaders’ politically.

Otherwise, why should President Sirisena, when he was planning to contest for the presidency for a second term grant pardon and release a monk who was noted for his anti-Muslim activities and was in prison for contempt of court? Shamelessly, a couple of Muslim politicians were also reported to have requested the President to release that monk. In this growing atmosphere of insecurity and hopelessness for Muslims, they are now facing an election to vote for a new president. What choice have they got?

If Muslims have any rational understanding about the true nature of party politics in this country, and if they are interested in the long term interest of themselves and their offspring, they should first learn to accept the advice of their political and even religious leaders with lots of reservation.

These leaders are sanctimonious and are worried more about their own future than that of the community. The community’s real issues are not about mosques, madrasas, female attire and halal food, as bandied about by Muslim politicians, but about landlessness, homelessness, poverty, unemployment, drug addiction and discrimination. These are also issues confronting citizens of other communities. Therefore, Muslims need a president and a government that tackles these issues with a comprehensive long term strategy and treat everyone equally with justice and fairness.

The cabinet should consist of technocrats and public administration must be run by meritocracy.

Contrary to what some Muslim leaders are saying, there are no unique and exclusive rights for Muslims in this country that should be denied to others. As Sri Lankans every one of its citizens share the same rights and responsibilities. If this is understood, then Muslim voters should choose that candidate for presidency who guarantees equality of treatment and justice to all.

Presidential Election

In this Presidential Election, the choice is narrowed down to three candidates, Gotha (SLPP), Sajith (UNP) and Anura (NPP). Of the three, the first two are undoubtedly under the clutches of ultra-nationalist Buddhists. Apart from Gota’s and Sajith’s lavish but irresponsible, unaffordable and uncoordinated promises regarding economy and welfare, these two are unwilling to repudiate the ultranationalist agenda of the supremacists. That agenda goes far beyond the foremost status afforded to Buddhism by the Constitution.

Supremacists want positive discrimination in favour of Buddhists in every sector of the economy and polity. Therefore, whether Gotha or Sajith, Muslims are not going to get justice and fairness. To win the trust of the minorities these candidates should make their position clear regarding Buddhist supremacists. While, the Buddhist far right is fully behind Gotha, Sajith cannot afford to antagonise them. This is the core of the dilemma confronting the two minorities in this election, and this is where the importance of the third candidate, Anura Kumara Dissanayake comes into prominence.

AKD with his NPP campaign platform is the only one that speaks about the fundamental issues confronting the nation. Eradicating corruption and wastage in public administration, downsizing omnibus cabinets, introducing coordinated and responsible economic reforms without upsetting too much the market paradigm, strengthening the rule of law, and promoting national harmony are some of the attractive features detectable from NPP manifesto.

More importantly, NPP is not in favour of any religion and its hierocracy to play a role in national politics. NPP in other words, is the emerging New Left in the country, which is different from the pre-Cold War left. There is no better government in a plural democracy than one that treats every component of that pluralism equally and on the basis of merit. NPP promises this. What more do Muslims and other minorities want?

Without sympathy and support from the majority community minorities have no chance of winning any of their demands. NPP is an alternative force that is rooted within the majority but speaking inclusively and genuinely on behalf of the nation as a whole. If Muslims are wise enough they should vote for AKD on the 16th to strengthen NPP in the next parliament. Voting for AKD is part of a long term strategy to save the country and its people from pseudo-patriots and profiteers. NPP is also the answer to the challenge from the Buddhist far right.

It is time Muslim public realise that they had been taken for a ride by their own leaders for a long time. Now, in chutzpah one Muslim professional has the nerve to threaten the community that if Muslims do not vote for his candidate and join the bandwagon there would be a terrible backlash. Worse than what they are facing now? To put it bluntly, Muslims should reject both leading candidates and go with the third. Their destiny after 2019 lies only in turning to the left.

(The writer is attached to the School of Business and Governance, Murdoch University, Western Australia.)