Sunday Apr 20, 2025

Sunday Apr 20, 2025

Saturday, 15 August 2020 00:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

“The world is what it is…”

“The world is what it is…”

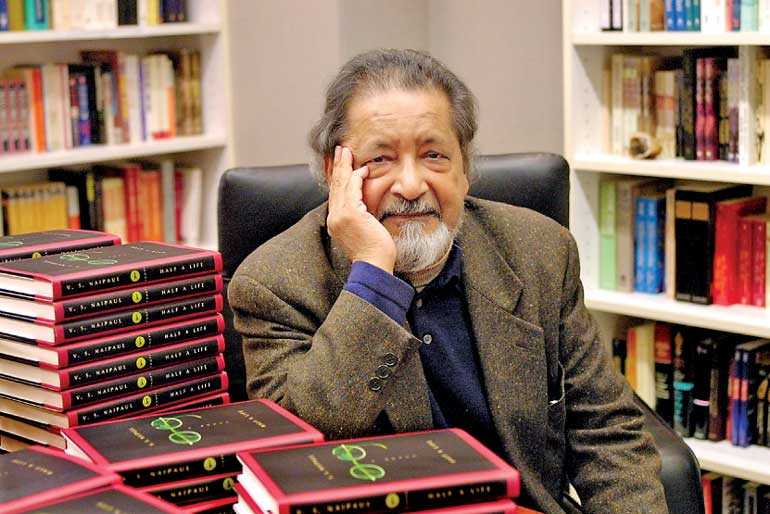

Exquisite craftsman of the English language, magnificent story teller, master of the unsparing nonfiction narrative, V.S. Naipaul, passed away on 11 August 2018.

Grandson of an indentured Indian labourer shipped willy-nilly to a Caribbean island to work the newly-established sugar farms, the Naipaul journey is an amazing modern era story of colonialism, migration, displacement and finally, of freedom.

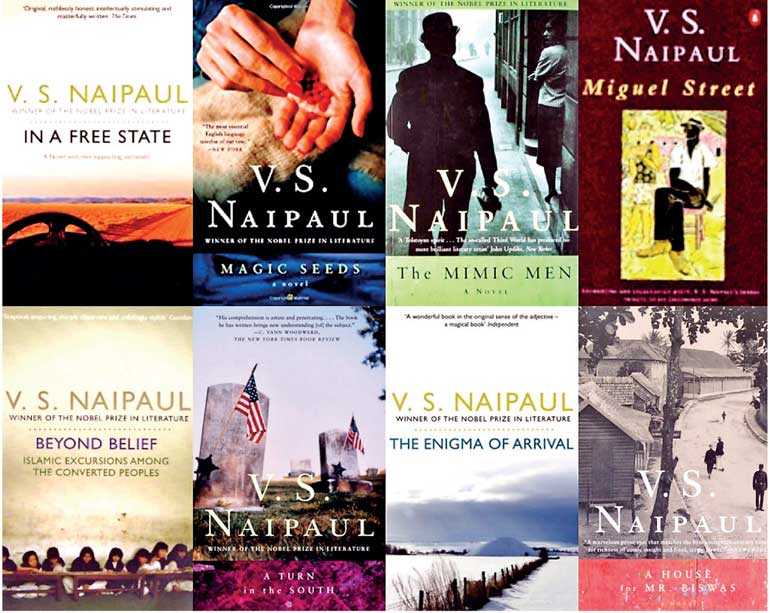

From Trinidad the talented young Naipaul won a scholarship to Oxford to study English literature. Difficult times followed, while the budding author struggled to find his feet in an austere post-World War 2 England. Then, came the compelling novels announcing the arrival of an extraordinary talent; ‘The Mystic Masseur,’ ‘A House for Mr. Biswas,’ ‘Miguel Street,’ ‘Mimic Men,’ ‘A Bend in the River,’ ‘The Enigma of Arrival’ – literary masterpieces, hailed by critics as comparable to the greats like Conrad, Dickens and Tolstoy.

It is however in his riveting non-fiction, travel writing to put in limply; a searing juggernaut into post-colonial societies, and the corroded souls inhabiting them, that Naipaul stands on Olympian heights.

To attempt to review Naipaul’s wide ranging coverage of a large swath of humanity in one short tribute is daunting. However, we can offer a few extracts from some of his writings, imploring the reader to explore further.

Naipaul’s’ first visit to India as a young man of 29 (in the early 1960s) brought forth “An Area of Darkness”, the first of his monumental trilogy of the homecoming of the immigrant Indian.

The youthful tourist brings with him on ship a few bottles of whisky, which, true to form, are ‘seized’ by the Bombay Customs. It is a mindless act of bureaucracy; the traveller may reclaim them later.

Naipaul describes his torment at the hands of the ‘License Raj’ thus.

“To be in Bombay was to be exhausted. The moist heat sapped energy and will, and some days passed before I decided to recover my bottles.

One step a day: this was my rule. And it was not until the following afternoon that I took a taxi back to the docks. The customs officer in white and the degraded man in blue (menial worker) were surprised to see me.

‘Did you leave something behind here?’

‘I left two bottles of liquor’

‘You didn’t. We seized two bottles from you. They were sealed in your presence’

‘That is what I meant. I’ve come to get them back’

‘But we don’t keep seized liquor here. Everything we seize and seal is sent off at once to the New Customs Office’

My taxi was searched on the way out.

The New Customs Office was a large, two-storeyed PWD building, governmentally gloomy, and it was as thronged as a court-house.

Upstairs I stood in a slow queue, at the end of which I discovered only an accountant.

‘You don’t want me. You want that officer in the white pants, over there. He is a nice fellow.’

I went to him

‘You have your liquor permit?’

I showed him the stamped and signed foolscap sheaf.

‘You have your transport permit?’

It was the first time I had heard of this permit. I was exhausted, sweating and when I opened my mouth to speak I found I was on the verge of tears.

I thrust all the papers I had at him: my liquor permit, my customs receipt, my passport, my receipt for wharfage charges, and my tourist introduction card.

‘What is a transport permit? Why didn’t they give it to me? I am going to write to the papers about this’

‘I wish you would’ said the customs officer ‘I keep telling them that they must tell the people about this transport permit. Not only for you. We had an American here yesterday who said he was going to break the bottle as soon as he got it.’

Naipaul visited India again in the early 1970s, during the turmoil of the emergency rule of Indira Gandhi. In 1977 came ‘India – A Wounded Civilization’.

V.S. Naipaul

“The princes of India – their number and variety reflecting to a large extent the chaos that had come to the country with the break-up of the Mughal Empire, losing real power in the British time. Through generations of idle servitude, they had grown to specialise only in style, a bogus, extinguishable glamour.

The power of this prince had continued; he had become an energetic entrepreneur. But in his own eyes, and in the eyes of those who served him, he remained a prince.

‘What keeps a country together? Love, love and affection. That is our Indian way…You can feed my dog. But he won’t obey you. He’ll obey me. Where is the economics in that? That’s love and affection…. For twenty-eight years until 1947, I ruled this State. Power of life and death…”

“In 1971, after she split the Congress, Mrs. Gandhi called a midterm election. I followed this election in one constituency, Ajmer, in the semi-desert state of Rajasthan. The candidate standing against Mrs. Gandhi was a blind old congressman who had taken part in the independence struggle and had gone to jail. He was a little vain of having gone to jail, and spoke as though the young people coming up who hadn’t gone to jail (and couldn’t have, because the British had gone away twenty-five years ago) couldn’t be said to have a ‘record of service’.

I asked him one day, as we were racing across the desert in his campaign jeep, what it was about Gandhi that he particularly admired. He said without hesitation that he admired Gandhi for going to Buckingham Palace in 1931 in a dhoti; that act ‘put the picture of poor India before the world’. As though the world didn’t know…”

“No other country was more fitted to welcome a conqueror; no other conqueror was more welcome than the British” Naipaul wrote. “While dominating India they expressed their contempt for it, and projected England; and Indians were forced into a nationalism which in the beginning was like a mimicry of the British”

Then to Africa “I travel to discover other states of mind,” wrote Naipaul. He went to Congo, the former Belgian colony, renamed Zaire. In ‘A New King for the Congo,’ Naipaul writes:

“The man who made himself the King of this land used to be called Joseph Mobutu.His father was a cook. But Joseph educated himself and at some time was a journalist. In 1960 when the country became independent Mobutu was thirty, a sergeant in the local Force Publique, which became the Congolese army. In 1965, as General Mobutu, he seized power. He abandoned the name Joseph and is now known as Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga.

It is said that the last five words of his name are a reference to sexual virility which an African chief must possess: he is the cock that leaves no hen alone. But the words may only be symbolic. Because as chief, Mobutu is married to his people.

He is citizen, chief, king, revolutionary, an African freedom fighter supported by spirits of the ancestors.

Muhammad Ali fought George Foreman in Kinshasa last November. Ali won: but the victor, in Zaire, was Mobutu. A big hoarding outside the stadium says ‘A fight between two blacks, in a black nation, organised by blacks and seen by the whole world is a victory for Mobutism”

“He is the man, young but palpitating with wisdom and dynamism, who during the dark days of secessions and rebellions thought through to the heart of the problem.”

(From a University of Zaire publication.)

The fantasy ended in the 1990s amid tribal and secessionists warring, Mobutu fled the country to Morocco. Today, nearly half the population of the Republic of Congo (renamed again, after Mobutu fled), live below the poverty line. The GDP per capita of Congo is approximately $ 1,500.

Later, Naipaul turned his eyes to the lands of faith; Iran, Pakistan, Malaysia, Indonesia, touring the non-Arab Muslim countries extensively. These journeys produced two trailblazing volumes, ‘Among the Believers’ and ‘Beyond Belief’. He wrote of Pakistan:

“It had a simple, terrible flaw. Even with the frightful communal flight, a great number of Muslims remained in India making it the world’s second largest Muslim country and they included the most experienced politically. Without them, the State languished or rather only the armed forces flourished, becoming masters, a country within a country.

The State withered. But faith didn’t. Failure only led back to the faith. If the State failed it was not because the dream was flawed or the faith flawed; it could only be because men had failed the faith. A purer and purer faith began to be called for.”

More than half a century of independence, many of the former colonies are deep in the mire of tyranny, corruption and overall dereliction. Inadequate men, with a small clique of collaborators, most times family members, rule by bribery, secret police and violence. Periodically, hopes are raised by various devises; new governments, new constitutions, fancy trade agreements, mega projects announced with fanfare, only to be disappointed by failure, inevitably expectations turning into cynicism.

Naipaul’s frighteningly acute expositions of the former colonies, the people and their palpable failings are not without its deniers. Caribbean born mixed race poet and writer Derek Walcott, winner of the 1992 Nobel Prize in literature referred to Naipaul in a poem as VS, ‘Nightfall,’ arguing that Naipaul was scarred by his revulsion towards negroes, probity of his writing was in essence a self-disfiguring sneer. Nevertheless, Walcott was pleased when Naipaul was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature (in 2001), “It will mean something for the region.”

V.S. Naipaul’s younger brother Shiva Naipaul, who followed his famous brother to Oxford several years later to study literature, wrote: “The longer I live, the more convinced I become that one of the greatest honours we can confer on other people is to see them as they are, to recognise not only that they exist, but that they exist in specific ways, and have specific realities.”

Perhaps this is the main lesson in Naipaul. People are different, they exist in different realities.

To view their foibles and fault lines, the reality of their recurring failure through rose coloured glasses, indulge in sentimentality, explain them away or delight in wishful thinking, is not for him. He took the world for what it is.

Ruth Jhabvalla, German-born Jewish writer, is the only person to have won both a Booker Prize as well as an Oscar (for screenplays). She married Indian architect Cyrus Jhabvalla and lived in India from 1951 to 1975, when she moved to New York.

“I cannot tell you what a difference it makes, how encouraging it is in the midst of one’s own loneliness and isolation, to have someone talk such brilliant sense about this place, after all the lies, all the jargon mouthed by people either too naïve or too stupid or too crafty to look and talk straight,” she wrote Naipaul after meeting him in India.

Not so long ago Naipaul savaged Tony Blair calling him “a pirate, heading a socialist revolution, destroying the idea of civilisation in this country and creating a plebeian culture.”

Writer and conservative politician David Pryce-Jones pays tribute to Naipaul, thus (‘Naipaul is truly a Nobel man in a free state’):

“Victimhood might have been his central theme, granted his background. Not at all, that same determination to be a writer also liberated him from self-pity. Each one of us, his books declare, can choose to be a free individual. It is a matter of will and choice, and above all intellect. Critics have sometimes argued that people-in the Third World especially, are trapped in their culture and history, without possibility of choice, and can only be free if others make them so. To them, V.S. Naipaul’s vision that they have to take responsibility for themselves can seem like some sort of First World privilege, and a conservative philosophy at that.”