Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Tuesday, 23 June 2020 00:42 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Global overview

National debt and fiscal ability are two stretch-words often reverberating world over during these pandemic/crisis times. As governments all around are pushing their boundaries to salvage national economies and avoid damaging spill-over effects, especially on vulnerable sections such as small and medium business holders, entrepreneurs, labour markets etc., such measures are invariably linked to the former important factors.

Nevertheless, whether it’s big or small, governments world over have been indifferent and made it a national duty to stretch their balance sheets to accommodate various economic stimulus by way of loan injections to struggling enterprises/industries, payroll backing, tax breaks, expansions of unemployment insurance covers, direct pay-outs to lower and middle income households, deferment of public fees/utility expenses, penalty

waivers, etc.

To complement the above cause, with respect advanced economies such as US, UK, Europe led by Germany and Japan have leveraged on their persistent sub-zero or negative interest rate and low inflation regimes to comfortably raise more debt resulting in widening Fiscal gaps. To call it another way in Central Bank parlance, ‘monetising debt’ by way of Treasury and Central Bank collaboration (e.g.: The Federal Reserve buying Treasury issued bonds in US).

Underlying economics

To the aid of such measures, economists argue that countries like US, UK and Japan which command high capital mobility and ability to raise debt (via bonds) in respective reserve currencies, may continue to fund such increased crisis-spending without having to increase follow-on fiscal costs (i.e. raising taxes) to the economies. Essentially not triggering a hyperinflationary environment as well.

This school of thought is widely popularised lately under the ‘Modern Monetary Theory’ (MMT) concept. Japan stands as a typical example for these results whilst running the highest debt: GDP ratio (which is currently in excess of 220%) in the world for the longest period and yet been unable to push-up the inflation for decades. Similarly, US and UK experiencing low inflation levels for longer periods despite the rising debt: GDP.

To supplement this cause-effect further, it is said that advanced economies which carry persistently lower risk-adjusted interest rates (e.g.: Treasury Inflation Protected Securities – TIPS in US) than respective growth rates (i.e. nominal GDP growth) remain in a better position to do the debt rollovers (issuance of incremental debt) without resorting to a public tax-increase regime. This has been extensively reviewed by the renowned scholarly Professor and former IMF Chief Economist, Olivier Blanchard in his research published in early 2019 at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

To put this in US context, this can be pointed to the fact that 10-year nominal bond rates (safe or risk-free rate) hovering near 3% which is lower than the country’s nominal GDP growth forecast of around 4% (2% real growth + 2% inflation) during Q1-2019.

In essence, as the debt servicing cost (interest) is cheaper than the earnings return (growth) in the economy, debt created by the State is bound to be self-liquidating in nature, provided that rest of the conditions remain unchanged. In turn, this provides an incentive for such governments to be more fiscally expansive without the fear of adverse spillover effects in later periods. Nobel Laureate US Economist Paul Krugman is another opinionist who acknowledges this rationality put up by Prof. Olivier Blanchard.

As specifically mentioned, even though the captioned basis is largely valid with respect to developed economies, the viability of such rationale in emerging markets remain highly constrained by factors such as currency weakness, higher interest rates and intricacies in capital flows. Due to these reasons, even during current crisis times where little or no push-pull inflationary pressures are present, the headroom for monetising debt by developing economies remain largely restrained. In other words, Fiscal expansion or government spending to support various stimulus measures in the economy are limit-bound and require close reviewing.

The same point is very much valid for Sri Lanka who has been persistently running a Fiscal deficit averaging to 6.3% for the last decade. This is in addition to the deficits maintained in country’s Current account. Owing to such reasons, it is needless to mention that Sri Lanka’s national debt has spiralled over the years leading to its current state of boiling point.

On top of such existing debt backlog, the additional cost created to the State by the current pandemic are expected to put further strain on the Fiscal status for foreseeable periods unless drastic reforms are expedited.

Due to these developments, national debt status has become the buzzword lately in many circles and discussions within the country. Given its great importance, the following seek to shed a light on Sri Lanka’s current debt status and several paths to be explored by the State actively in terms of raising future debt in international markets.

National debt burden

It is no secret that Sri Lanka is overwhelmed by a debt cycle spinning one fiscal period to another. In the face of continuous deficits carried in both fiscal (State income vs. expenditure) and current account (export income vs. import cost) balances which respectively accounted for 6.8% and 2.7% against the GDP in 2019, had naturally forced the country to seek debt assistance for managing its affairs and recurring debt repayments.

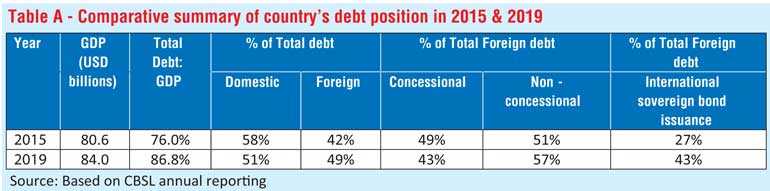

To put a perspective on country’s present debt status as per the CBSL (Central Bank) records in 2019, country’s total debt comprising of both domestic and foreign stood at Rs. 13.03 trillion. Comparatively this figure in 2015 was Rs. 8.7 trillion. For the same period, total debt: GDP increased to 86.8% from 76%. On an aside, whilst the country’s GDP or national output grew by mere 4.2% during 2015-2019 period, the corresponding debt burden has outgrown by almost 50%.

As the captioned tabulated data suggests, over the above period, Sri Lanka has been more reliant on raising its debt internationally than domestically. As figures indicate, the foreign debt component which stood at 42% in 2015 against total national debt has gradually increased to 49% by 2019. More of a natural phenomenon for a country which simultaneously carries a weaker trade balance putting pressure on the primary source of net foreign income.

Whilst 51% of total foreign debt in 2015 attributed to non-concessionary loans obtained on commercial terms, this figure has climbed to 57% by 2019. This is in turn points to the increasing incremental debt servicing cost (i.e. interest) associated with the foreign borrowings.

Ironically, the fact that Sri Lanka was elevated to the ‘upper middle income’ status during 2019, consequently took away the country’s eligibility to obtain foreign denominated loans/grants by supranational entities like IMF under concessionary schemes at reduced interest rates. Instead, now Sri Lanka is compelled to avail those loans at a relatively higher cost owing to the country’s elevated per capita income status as per the World Bank classification.

As a result of above developments, the issuance of foreign currency denominated bonds out of total foreign debt has been gradually increased to 43% in 2019 (i.e. $ 4.4 billion) compared to 27% reflected five years ago (i.e. $ 2.15 billion). Realistically, as this trend is expected to be continued for the foreseeable future, Sri Lanka’s creditor status or sovereign risk rating as perceived by the international investor community naturally becomes one of the critical yardsticks dictating the country risk premium involved with foreign borrowings.

In view of recent Issuer Default rating downgrades by both Fitch and S&P Ratings, the bonds issued (i.e. borrowings) by Sri Lanka falls six notches below that of ‘investment-graded’ bonds traded globally. In other words which continues to categorise country’s issued and proposed debt under ‘junk’ investments.

Therefore, speedy reforms to prop up the country’s external and fiscal sector performances in the long run remain a critical task in order to improve Sri Lanka’s credit worthiness in the eyes of international investor community. Sri Lanka is already facing constraints in international debt markets as evidenced by the recent undersubscribed SLDB issuances during March and April this year. In addition, the existing USD bonds issued by Sri Lanka which are currently trading considerably lower than their par (face value) despite the higher coupons, suggests the aggravated risk-on status of country’s debt instruments as perceived by international investors. Hence, the failure to expedite corrective economic reforms may lead to more stress and further investment appeal deterioration in coming periods. As CBSL annual data suggests, total foreign debt as a percentage against country’s exports as of 2019 FYE posted at 184.4% which accumulates to a USD figure of 22.02 billion. Moreover, total foreign debt service (annual principal + interest) as against the exports in 2019 has spiked to 23.7% from reported 16% in 2018. Similarly, the interest service alone has climbed to 7.2% from 6.5% for the same periods. Sustainable way out from this chronic problem lies with the strengthening of country’s External sector for persistent periods. This leads to the major improvements in key sources of foreign inflows to the country which stand under exports, tourism, worker remittances and FDIs.

Collectively these sources have contributed to $ 23.47 billion in 2019 which is in fact down from $ 25.42 billion reported a year earlier. Whilst annual inflows from tourism and worker remittances will remain more susceptible for external factors, as proven during current crisis times, greater emphasis should be given to drive the country’s exports and FDIs in the long run which are relatively less cyclical and complementary in nature (as 37% of FDIs has flown into exports led economic zones during 2019).

In view of current developments and future reliance on issuing debt internationally by the country, the following captures some of the important directions which Sri Lanka can explore both internally and externally in terms of better approaching the international debt markets;

nTargeting of sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs): As per the latest SWFI (Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, USA) ranking, Norway SWF with $ 1.186 trillion assets ranks as the first whilst China remains in the second position globally. Interestingly, out of the top 15 global SWFs, almost half of the largest asset pools are domiciled in the Middle East (ME). These include the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, Investment Corporation of Dubai and Mudabala Investment Company funds held by UAE and the rest held by KSA, Qatar, Kuwait and Turkey. Additionally, another two SWFs managed by the Singapore Government.

It is well-known that the majority of Sri Lanka’s worker remittances are originated from the ME which has the highest number of Sri Lankan expat workers, including a large pool of banking and finance professionals employed in ME based banks and certain federal authorities. This includes some of the longest-serving Sri Lankan missions abroad to date.

Considering these facts, Sri Lanka should drive a focused and professional approach to pitch its International Sovereign Bonds (ISB) and Sri Lanka Development Bonds (SLDB) propositions to federal authorities based in the ME to tap these investment pools effectively.

Ideally, establishing a designated ‘National Investment Authority’ comprising of competent professionals with a background of international banking experience and leveraging on the Sri Lankan banking/finance professional network based in the ME, remain as certain important avenues to be explored by the Treasury and CBSL during future debt issuance endeavours.

Similarly, a work plan should be implemented to tap SWFs held by countries such as Singapore (country with Sri Lankan professional expats) and Norway (once a peace brokering country involved in Sri Lanka’s war times) to broad-base the reach.

In addition to the large investment pools held by these SWFs and diversified investment mandates, persistent lower interest rate regimes prevalent in these economies probably might help the Sri Lanka’s cause of raising future bond issuances cost-effectively (in the event of competitive bidding) and with possible higher allocations.

nNon-USD based bond issuances: As a timely step taken by the former CBSL Governor Dr. Indrajit Coomaraswamy, the country made its intention public for the first time to issue bonds denominated in YEN (Samurai bonds) and YUAN (Panda bonds) during 2019. However due to the long-drawn formality issues and follow-on presidential election, the plan was shelved.

Japan which persistently runs negative interest rates and sub-zero inflation levels also owns one of the most-stable currencies (i.e. Yen) globally. Japan’s stature as the world’s third strongest economy and safe haven currency status make the country one of the best-suited and less-volatile financial markets to raise non-USD debt by the GoSL.

Similarly, China remains as a compelling alternative with its global status (second biggest economy) as a powerhouse for manufacturing and strong-defender of its currency ably supported by the large wealth. Not to forget, China’s vested interests in Sri Lanka, where the latter already being a benefactor of China’s mammoth Belt & Road initiative, validates the then CBSL Governor’s rational for a national strategy to raise non-greenback international bonds in these markets.

Understandably, Sri Lanka can better leverage on the historical ties with Japan and China which spans for centuries long to tap these debt markets, possibly more competitively compared to more risk-driven markets in US or Europe.

Additionally, prospects in financial markets like Norway (largest SWF and stable currency status) and Singapore (strong economy and safe haven status) also to be explored by Sri Lanka in its endeavour to raise non-USD debt in future.

nTapping into green bond market: Sovereign green bond issuances are fast-becoming an attractive platform world over to raise capital needed for specific green-compliant projects. Ideally in Sri Lanka’s case, the option should be actively explored for future project-financing in renewable-energy initiatives like mega hydro or wind based power generation or possibly towards a national project for waste recycling plants etc. whereas the cost (i.e. coupon rate) will be relatively lower than that of conventional vanilla debt instruments.

Being a country majorly reliant on fossil fuel and running an annual bill of $ 3.9 billion (almost one-third of annual exports in 2019), Sri Lanka can purposefully explore this alternative to raise capital for future greener development projects. In fact, neighbourly India is actively pursuing this option and has reportedly raised $ 10.3 billion worth of debt during 1H-2019, becoming the second largest emerging green-bond market after China.

Tax benefits availed for investors on green bond investments which are in compliant with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) may provide a viable cost-effective route for Sri Lanka to actively strategise a national policy to raise foreign debt through this option in the future.

nEstablishing a National Investment Authority: As noted earlier, the country should ideally form/develop a standalone national body comprising of bankers/financial market professionals with international expertise and networking to liaise with the CBSL in strategising future ISB, SLDB or structured debt issuances intended for international debt/capital markets. Realistically speaking, as Sri Lanka is compelled to issue more debt internationally in order to manage the rollover risk of existing debt, the captioned will be a prudent move towards country’s readiness for foreseeable future.

Conclusion

As noted earlier, whilst it is paramount that the country uplift its investor appeal in the long run through fiscal and external sector corrections and new reforms, similar emphasis should be given to explore the captioned ways to raise foreign debt sustainably in future periods. Such strategies can be looked upon in tandem with the CBSL’s ongoing efforts to raise foreign flows by way of SWAP arrangements with fellow Central Banks, syndicate debt (where all-in price might be cheaper than bonds), etc. to manage existing debt repayments and future rollovers.

[The writer, CMA (AUS), ACIM (UK), CFA Candidacy, is a professional with 18+ years of banking experience including over nine years of corporate/multinational banking exposure in both UAE and Sri Lanka. Presently based in UAE as a banker and independent researcher of macroeconomics, banking and international financial markets. He can be reached via email – Shamika902102gmail.com or LinkedIn – linkedin.com/in/Shamika-ramanayake-15656970.]