Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 18 April 2018 00:07 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

If everyone in the construction team does not play their own part, the quality of the outcome cannot be achieved

“Quality is never an accident; it is always the result of high intentions, sincere effort, intelligent direction and skilful execution; it represents the wise choice of many alternatives”

– William A Foster

The First Step

I commenced my career as an engineer with a Sri Lankan semi-Government engineering consultancy organisation. I was immediately assigned to a major hydro-power construction project of the accelerated Mahaweli Development Scheme.

I directly reported to the senior staff of the Engineering Consultant which was a conglomerate of two German and a Swiss engineering consultancy firms. By the way, the international contractor for the project was also a construction consortium consisted of two German contractors who had been listed within the top five construction companies in Germany. So, this opportunity was a seventh heaven for a graduate engineer.

I still feel the sheer satisfaction of achieving high quality construction and project management experience which immensely helped me, later, to secure a senior position in NSW State Government in Australia. Also, it was a unique opportunity for me to witness the thought process of the expatriate consultant and the contractor on achieving a high quality product.

After I left this project, I joined the Sri Lankan public sector with the intention of applying valuable experience I gained to make a difference to their engineering affairs. However, I had a limited success. The professional leaders whom I was associated with just wanted me to maintain the status quo. This is not to be interpreted as a criticism of engineering competencies of the local engineers. It was due to their limited exposure to the ’quality’ concept and their fear of leaving own comfort zones.

I believe that the organisational politics and the work culture played a part to make them ineffective in fusing the quality into their project outputs. So, the focus of this article is to recount a few lessons I learnt from the Germans to inspire young engineers and construction personnel, especially in the Sri Lankan public sector. Let me begin with a story.

One day, a local worker who worked for the German contractor, mockingly asked his expatriate supervisor to explain the ‘S1 finish’ marked on a construction drawing. By the way, S 1, 2, 3 were the symbols used to indicate the hierarchy of surface finishes for concrete and the S1 was the smoothest. The German supervisor shot back aloud, “Pull your… pants down and rub your… bum on the concrete. If you get any scratches, it is not ‘S1’.” The poor guy got his first lesson on surface finish quality.

Quality

The definition of the term ‘quality’ for a product or a service is dependent on one’s perspective per se customer’s perspective, specified standard perspective, etc. The late Professor of the Harvard Business School, David A. Garvin defined the quality under eight dimensions: Performance, Features, Reliability, Conformance, Durability, Serviceability, Aesthetics and Perceived. So, defining quality is not a straightforward affair and this is not a forum for that.

Quality can simply be put as the ‘conformance to the set product requirements’. (Crosby, 1979). The product requirements are set by the designer after taking into account the customer expectations. I believe that the readers deserve a simple definition for ‘quality’ like “meeting or exceeding the customer expectations” because that is what really matters, at the end.

As my focus is the construction outputs in Sri Lanka, the Sri Lankan community are the customers here. As a citizen of Sri Lanka or simply as a customer, I have a right to announce my opinion. I would say that I am not happy with the quality of the majority of construction works in Sri Lanka as the quality does not meet my expectations.

However, would my cry alone make any difference to the current trend? Probably not.

So, I have a different approach. I will tell you a few true stories. If my narratives kindle any novel ideas on quality, then you all have a right to make a huge cry until someone responsible for the quality of local construction works listens. Let me try.

Lesson learnt 1: Quality is a reflection of pride

The doer of an activity automatically owns the output as well. Hence, the pride of the doer is at stake on the quality of the output. If a poor quality output is delivered, it will tarnish doer’s image and a stakeholder has a right to protest, saying, “this is not good enough”.

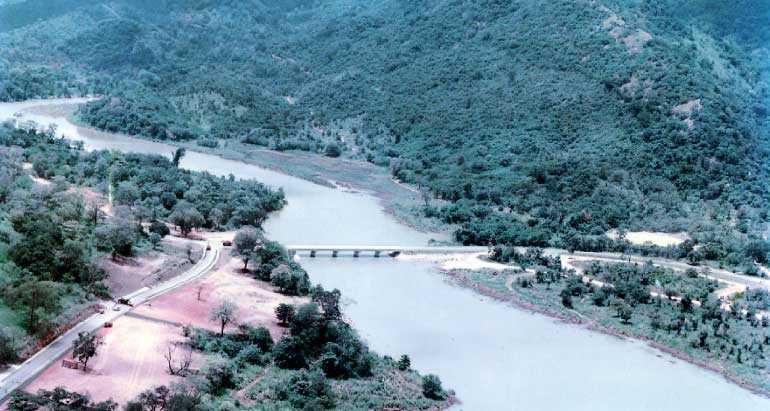

There was a 100-metre span, uniquely designed concrete bridge to be built. I was the project engineer in charge, on behalf of the German engineering consultant. The German contractor completed the construction works within five months. Arrangements were finalised to remove the coffer dams built around the four massive piers. By the way, the coffer dams are built to divert the natural water course to allow construction works.

Just before I signed the authorisation papers, the contractor requested two more days to attend some finishing works on piers. I was puzzled as the piers were perfect for me. He took me to the site and showed me a few tiny holes on concrete piers and also a few uneven concrete surfaces on piers due to the displacement of the formwork and the shuttering. The defects were not structural defects. He wanted to rectify those by putting epoxy fillings and subsequent grinding.

I explained him that these sections of the piers would be well under water and also the defects were so minor. He looked at me sternly and waved the construction drawing. “Look at this paper, do you see a crooked line? All these are smooth lines and curves. I want to see the same at site as well. This bridge is mine and also yours. My name is also written there even if it goes under water.” I was speechless. It took two days for two workers to complete the job under the baking sun.

I never came across a construction supervisor who had such a passion and pride towards own construction work. That rare person happened to be a foreigner.

Lesson learnt 2: Quality cannot be achieved by just having money; it needs an attitude.

“Quality is not an act, it is a habit” – Aristotle.

The contractor’s job is to build the structure in accordance with the engineering specifications and the construction drawings. It is easy to maintain quality on construction documentation as the codes of practice dictate terms on that. However, the quality of these documents mean nothing, if the builder does not follow the specified construction details.

The German contractor imported formwork and shuttering material from Germany. The formwork was sturdy and the shuttering mounted on formwork had a special coating which makes the concrete surface very smooth. (Remember S1!)

The formwork and the shuttering for a huge concrete dam was a significant expenditure. The contractor could have saved a lot by selecting a cheaper local plywood material. There was a contract condition encouraging local material use. The problem for the contractor was that the local materials did not meet their quality expectations.

If local materials had been used, Sri Lankan authorities and the politicians would have been happy. However, the German contractor refused to use local material for this. They pointed out the inferior quality of the shuttering material in the local market and the resulting rough finish.

If local materials had been used, Sri Lankan authorities and the politicians would have been happy. However, the German contractor refused to use local material for this. They pointed out the inferior quality of the shuttering material in the local market and the resulting rough finish.

Local contractors often used warped, uneven timber material as formworks and shuttering. Our contractors and workers don’t give a damn about how the structure would look at the end as long as the construction is done to meet the bare minimum engineering standards. In Colombo and suburbs, could anyone find a drain with a smooth transition structural surfaces? Local workers know that no one would be bothered to complain as it is the quality delivered by all.

By using such a high quality formworks and shuttering, the German contractor did not have to worry about repairing air pocket holes (honeycombs) on the concrete surface as the vibratory compaction of concrete along the highly smooth shuttering surface prevented the generation of air pockets. Otherwise a high cost could have been incurred to repair massive areas of concrete surfaces, especially on the long, curved spillway. So, the contractor made an informed decision to come up with quality material use and it eventually saved them money. The quality concept was in the veins of the German consultant and contractor.

Lesson learnt 3: Quality is about producing a product that lasts

This construction project had a concrete dam, a powerhouse, two large span bridges, a road network with over 100 culverts and a town water supply scheme.

When the culverts were constructed, the inlets and outlets of the culverts were transformed into, at least, 15-metre-long channels. The sides and the bed of each channel were protected with boulders embedded in concrete. Local workers and also some engineers commented that the contractor was trying to maximise the project costs as this work was a variation to the original project work.

So, I confronted the site project manager and queried on this. He attentively listened to me and asked: “What are the three main causes for a road failure?” I gave him a few engineering explanations which were perfectly right. He smiled and said: “I agree but remember the three most common causes are water, water and water.” Then only, I realised that he wanted to emphasise something else to me.

He continued: “You guys are very poor on maintenance. Given that, we make sure the road will last for a long time, without allowing water ingression to any part of the road. These drains will function for years. Also we build side drains for all these roads which are eventually connected to these channels. It does not matter for us these roads are located in a virtual jungle. Otherwise, one day you guys would complain that the Germans did a poor quality job.”

They proved me quality was to produce a product that will last long. By the way, the site project manager was absolutely correct on our maintenance practices. I drove on this road network after 20 years of the construction. I literally shed a tear or two, after seeing the roadsides were overgrown due to poor maintenance. As a credit to the contractor’s foresight and insight, the road structure itself was still intact.

Lesson learnt 4: Quality is the attention to details

The most stressful period of my whole career was the four-week period I acted as the Section Engineer. I had to deal with the German Chief Project Manager (CPM) daily basis. On the third day of my new assignment, when CPM came to the site early morning, I went to greet him as usual. He ignored me and did not even bother to shake my hand. I knew that this was not a good sign.

He suddenly roared: “The slope of this retaining wall is not right.” That was it and he stormed out of the site. I got the gradient of the wall checked and found it was slightly wrong. This was corrected afterwards. I still don’t know how he detected the error by his naked eye without taking any measurement.

Two days later, he asked me join a ride on his luxury SUV and he drove it along the newly-constructed road. While driving back and forth on each section of the road, he intermittently stopped and asked me to mark down some stretches on the road using a spray paint bottle. Finally, he stopped and called the German site supervisor and instructed him to remove 25 millimetre thick asphaltic layer of each marked section of the completed road and redo the construction. Even the site supervisor was stunned. I noticed that the supervisor asked the reasons for this reconstruction although I could not understand more than a few words of German language.

On the way back I politely asked the CPM, how he found out those sections were bad. He said: “Look at this built-in gradient meter attached to the dashboard. When there are dips on the road, it oscillates.” Again, I never met a Senior Project Manager in my professional career who was so attentive to the finer details. The German contractor finally agreed and reconstructed the marked road sections at their cost.

Lesson learnt 5: Quality is a collective achievement

The concrete for the dam and powerhouse had to be of optimum quality. A special brand of low heat cement variety was selected and the mixing of concrete was done using chilled water with added ice to control heat generation. I was in charge of one of night shift works of the powerhouse construction and I rejected a series of concrete trucks due to excessive temperature of concrete.

On that day, I rejected around 20 cubic metres of concrete and the local drivers were forced to take the trucks back from the site. However, I overheard the drivers complain through their walky-talkies to the local foreman of the concrete batching plant about my decision. I realised that they were up to something. Hence, I asked one of my technical officers to follow the trucks as the truckies were supposed to take the rejected concrete to the dump yard or to a work site that rejected concrete could be used for less stringent slope protection works.

My officer reported me that the drivers secretly added water to the same concrete and the trucks were on the way back to the site. I rejected the trucks again even without testing as the adding of water would alter the strength of concrete. I had evidence to prove adding of water to concrete. There, the local batching plant foreman was only interested in covering his mistakes (to avoid blame from his expatriate supervisor) and not about maintaining quality of the end product.

The point I want to make here is that if everyone in the construction team does not play their own part, the quality of the outcome cannot be achieved. The local workers should have realised that this dam and the powerhouse would be a national asset for us and our next generation and we must build a quality asset.

Lesson learnt 6: Quality is an outcome of continuous improvement

At the end of the project, the Engineering Consultant prepared the final project report, describing how the project was planned and implemented according to the designs and specifications. I had the privilege of writing one of the chapters of this report. While I was compiling my report, I noticed that my expatriate Section Engineer was working on another report. To collect information for his report, he consulted me and the site project managers.

When the time was right, I asked him about the contents of that report. He replied: “The report we hand over to the Sri Lankan Government is the success story. It is not the one in which we are really interested. This report is about the tragic events, where we failed, where we recovered and where we learnt our bitter lessons. You are not aware of many of those events. This report is a classified report. Copies of this report will go to the key project managers of our international branch offices and also to the principal contractor. We will, as a team, endeavour not to make same mistakes again and are determined to do a better quality job next time.”

I had the privilege of reading this classified report. It enhanced the horizons of my project management knowledge. By the way, my Section Engineer politely declined to give me a copy to keep. No wonder the Germans are well known for their excellence in technology through their continuous improvement mindset.

It should be noted here that the German consultant and the contractor only gave the leadership and the guidance and it was the local engineers and the workers who performed accordingly. They were competent enough to carry out the instructions. So, what is missing in the Sri Lankan public sector is the professional leaders of such calibre.

I sincerely hope that the above few lessons would serve as a catalyst for the young local professionals in the construction field to search the excellence in quality construction.

(Eng. Janaka Seneviratne is a Chartered Professional Engineer, a Fellow and an International Professional Engineer of both the Institution of Engineers, Sri Lanka and Australia. He holds two Masters Degrees in Local Government Engineering and in Engineering Management and at present, works for the Australian NSW Local Government Sector. His mission is to share his 31 years of local and overseas experience to inspire Sri Lankan professionals. He is contactable via [email protected].)