Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Thursday, 28 October 2021 00:40 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Already, the tea industry is plagued with serious labour shortages and unable to even pluck the minimum required four rounds of plucking in the existing tea fields, resulting in crop and quality loss. Herbicide usage is universally accepted as a convenient, cost effective, good agronomic practice with benefit of timeliness, replicability, specificity, predictability and availability of required manpower and materials – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Since herbicides spraying was introduced as a form of weed management in the 1960s with Paraquat, plantations have used pre-emergent, residual, post-emergent, broad spectrum, systemic, translocated, and contact herbicides for weed management depending on bush cover, rainfall pattern, growth stage of weeds and tea bush.

Since herbicides spraying was introduced as a form of weed management in the 1960s with Paraquat, plantations have used pre-emergent, residual, post-emergent, broad spectrum, systemic, translocated, and contact herbicides for weed management depending on bush cover, rainfall pattern, growth stage of weeds and tea bush.

Plantations have not exclusively depended on herbicides for weed management but have used preventive, cultural, manual, biological, ecological chemical, mechanical and genetic weed management methods to control weeds found in the various stages of tea cultivation. Weeds were treated based on length of life cycle of weeds (annuals, bi-annuals, perennials), habitat (upland, lowland) morphology of weeds (broad leaved, grasses, sedges, shrubs, trees), harmfulness (soft, hard) and stem tenderness (woody or herbaceous).

Herbicide usage has followed TRI recommendation regarding selectivity (selective or non-selective herbicides), mode of action (contact or systemic), placement site (foliage applied or soil applied) and time of application (pre-emergent or post-emergent). According to the TRI, chemical weeding is the most convenient and cost-effective method among various techniques under integrated weed management. Herbicide spraying creates a mulch of dead weeds on the surface and improves water retention, adds organic matter and recycles nutrients removed by weeds. When manual weeding is done, weeds physically removed from the field carries away 32 kilos N, 40 kilos K and 320 kilos carbon from the field reducing the organic carbon and nutrients.

TRI has confirmed that without regular weeding, mature tea will have 20% yield loss after six months and if manual weeding is resorted to, yield loss after four months is 15%. Furthermore, when manual weeding is done; soil fertility and water holding capacity of soil is lost due to erosion and 30 cm to 45 cm of top soil is lost, leading to 30%–50% loss of crop productivity.

Currently, appropriate and recommended IWM systems are being undertaken, of which use of herbicides is a component. Currently two applications of herbicides are undertaken at a cost of around Rs. 12,000 per Ha per annum using around four workers per Ha for spraying. If manual weeding is done, 30-40 workers per Ha have to be used every three months; 120 to 160 workers per Ha at a cost of around Rs. 180,000. This is completely unaffordable as the weeding cost would increase by Rs. 130 on COP of tea. This is not practical and industry does not have labour to undertake such a labour intensive exercise.

Already, the tea industry is plagued with serious labour shortages and unable to even pluck the minimum required four rounds of plucking in the existing tea fields, resulting in crop and quality loss. Herbicide usage is universally accepted as a convenient, cost effective, good agronomic practice with benefit of timeliness, replicability, specificity, predictability and availability of required manpower and materials.

Weeds in the tea fields cause crop loss though competition for space, soil nutrients and soil water. Weeds compete and remove nutrients applied to tea bushes. Weeds also have an allelopathy effect on tea plants (Illuk and exudation of noxious substances from roots), host parasites (Lygus bug, Rosselina, Loranthus, Cuscuta) and cause soil loss through erosion when manually weeded and interfere in the agricultural and cultural operations.

The presence of weeds significantly reduce harvester productivity when weed foliage reaches plucking table, interfere in the harvesting operation reducing harvester output and income leading to reduced quality of life. Harvester safety and wellbeing at work is compromised with presence of leeches and reptiles in the fields because of profuse weed growth. Weeds reduce quality of made tea due to poor standard of harvested leaf and contamination of noxious weed foliage in made tea, leading to many unwarranted issues in terms of crop loss, quality loss and worker health, safety, earnings and livelihood related issues.

Before the advent of herbicides, weeding in the plantations were done using an implement, the sorandi/scraper, which led to a massive and an irreversible soil erosion. Conservation of soil in which the plant grow and the maintenance of soil fertility are two basic requirements for any crop, more so especially for a perennial vegetative harvest crop as tea and without fertile soil or depleted soil, plant life cannot be economically sustained.

TRI, after intensive research, concluded that in the first year clonal tea fields, more than 52 tons of soil/ha/year is lost due to erosion and more than 40 tons of soil /ha/year was lost due to erosion in seedling tea fields when “scraper” weeding was done. This level of soil loss affects directly in reducing soil fertility, soil water, soil micro-organisms, soil nutrients, rooting zone for plants, soil permeability and create hard pan. The use of scraper led to a scale of soil erosion that Government introduced a ‘Soil Conservation Act’ in 1958.

The Central Highlands of the country which boasted of a rich agricultural heritage suffered as a result of reduction of soil fertility and many agricultural holdings were abandoned leading to unemployment and poverty and cultivated tea lands reduced by about 50% in the Central Province as a result of poor land productivity.

It is common knowledge that 300 to 1,000 years are taken to build up one inch of soil. Manual weeding is not a recommended form of total weed management the world over and a well-managed clonal tea field using herbicides will lose only 330 kilos of soil per hectare. Manual weeding will also disturb the soil and encourage even more profuse growth of weeds in the field after soil disturbance as the number of weed seeds in the top 15 cm of top soil is found to be between 52 to 108 million according to research by the TRI.

After the introduction of herbicides, plantation management as a routine practice relied on Integrated Weed Management (IWM) for the control of weeds. Integrated Weed Management includes preventive methods, cultural methods, agronomic practices, manual weeding, chemical weeding, biological, ecological and mechanical methods of weed management. Even in chemical weed management until the recent past, the plantations had the benefit of a choice of a variety of appropriate TRI recommended herbicides that act in different methods to manage weeds e.g.: Paraquat as a contact herbicide, Simazine as a pre-emergent herbicide, Karmax/Diuron as a residual soil applied herbicide, MCPA for broad leaved weeds, Fernoxone as a plant growth regulating hormonal herbicide, Oxyfluorfen as a residual herbicide and glyphosate as a translocated herbicide, Glufosinate as a systemic herbicide, amongst others. The plantations had the benefit of using target specific weedicides for the many varieties of weeds found on the estates.

The Government banned the universally used herbicide Paraquat in 2004 in Sri Lanka, solely based on the illogical reasoning that farmers ingested Paraquat to commit suicide. All other tea growing economies competing with Sri Lanka still use Paraquat. The Government also banned the universally used herbicide glyphosate in 2015 and restored in 2019, again illogically on the unproven, unscientific, false premise and hypothesis that glyphosate was linked to CKDU. This has been proved wrong beyond any reasonable doubt by findings of WHO, several Government appointed committees, tree crop research institutes, universities, the Department of Agriculture, scientists, agriculture researchers, medical scientists and nephrologists in addition to expert and experiential knowledge of agriculture professionals and practitioners. Currently, Sri Lanka has only one recommended herbicide i.e. glyphosate and this too is not available since June 2021.

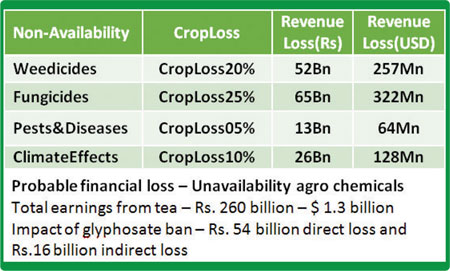

However, presently plantations have been compelled to use only glyphosate as a systemic herbicide and is not a practical method to control a wide range of weeds found in the plantations. The ‘Gramoxone’ ban in 2004 and the ‘glyphosate’ ban in 2015 made an irrecoverable impact on the plantation industry. Since 2016, Sri Lankan tea crop has come down to even below 300 million kilos per year from 340 million kilos levels previously, to 279 million kilos in 2020. This was clearly predicted through many communications and Newspaper articles in 2015 itself. About 10% of total tea extent was reduced from 222,000 Ha in 2013 to 200,000 Ha in 2020 as large extents of tea land was covered with weeds and was abandoned for the lack of weedicides after the glyphosate ban. The direct loss from loss of crop was about Rs. 15 billion per annum as a result.

TRI over a half a century of research has confirmed that without regular weeding, within six months a yield loss of 20% is expected and if manually weeded, yield loss is 15% within four months. The COP of Ceylon Tea which is the highest in the world will increase to an exorbitant amount with a yield loss and Ceylon Tea will not be competitive in global markets. Once weeds invade and cover the surface of the plucking table, it will interfere with the plucking operations and quality of leaf harvested will be poorer quality which will reduce our current sale average. Loss of traditional quality expected from Ceylon Tea will drive away traditional buyers to other competing teas and we will lose our hard-won markets which have been with us for over 100 years.

Weed foliage will get mixed with tea leaf and this will invariably contribute to further loss of quality and rejection of our tea as taste, chemical content and appearance of tea will vary significantly along with appearance of made tea. Harvesters will find it extremely difficult to clean the plucking surface covered in weeds which will result in lower crop and lower outputs. Low crops will result in reduced earnings, number of days of work, leading to reduced income. Reduced earnings will severely impact on their health, sustenance and ‘quality of life,’ leading to poverty and starvation which will eventually lead to massive social unrest.

Without weedicides, there will be profuse growth of weeds in fields which attract leeches, small insects and rodent animal life and dangerous reptiles which attract larger predators as experienced in the last five years during the glyphosate ban and this is a definite danger to workers in fields. Such danger from predators and reptiles will keep pluckers away from fields and reduce attendance at work which reduces tea worker’s income and lead to abandonment of vast areas of tea lands as experienced, leading to loss of tea crop eventually.

Pests and diseases in tea

Pests and diseases in tea

Plantation agriculture is spread across 46 agro-ecological regions in three rainfall zones and in three elevations and each geographic region exhibits its own distinctive ecological and environmental characteristics and pest fauna. Pests like insects, mite and nematodes are organisms that cause economic damage to tea plants and diseases in leaf, stem, branch and roots of tea bush resulting in conditions that interfere with normal physiological and crop generating functions. There are many perennial, seasonal, potential, occasional and secondary pests and diseases caused by biotic, pathological and parasitic agents as fungus, bacteria, virus, viroides, phytoplasmas, parasitic seeds and parasitic plants in tea cultivation. There are also physiological and non-parasitic diseases caused by sun scorch, cold, light, temperatures, humidity, water logging, soil pH and mineral deficiencies. In tea cultivation, all pests and disease treatments are specific, need based and targeted to protect the crop or the tea bush and if there are no pests; no pesticides are used.

Tea is subject to many pests and diseases from nursery to maturity, whatever the age of growth stage of the plant is in e.g.: Yellow Mite, Tea Tortrix, Nematodes and fungal diseases in the nursery and in new clearings and mature fields. Tea is subject to pests: Tea Tortrix, Nettle Grub, Red Mite, Scarlet Mite, Spider Mite, Purple Mite, Pink Mite, Lobster Caterpillar, Looper Caterpillar, Red Slug, Lygus Bug, Up Country and Low Country Live Wood Termite and Shot Hole Borer are some.

Apart from these, different parts of bush are subjected to specific diseases. Leaf is subject to Blister Blight, Brown Blight, Grey Blight, Black Blight, Red Rust, Oil Spot and Phloem Necrosis Disease. Stem is subject to Wood Rot, Collar, Stem and Branch Canker and Hypoxylon. Root is subject to Red, Black, White, Brown, Violet and Charcoal Root disease.

Pest and disease attacks, results in economic loss due to loss of crop, loss of quality and incur additional costs for control. It reduces land productivity, user efficiency and has detrimental effect on soil, water, air and environment, reduces the effectiveness of resources and inputs of land, labour and human resources and minimises worker attitudes and efficiencies. Pests and diseases have a significant impact on the appearance, taste and quality of made tea.

Sri Lanka has an annual average rainfall of 3,800 mm in the Up Country catchment areas and with a mean temperature of around 16.5 Degrees Celsius and humidity over 84% in areas like Nuwara Eliya, tea bushes easily succumb to pests and diseases. TRI has confirmed that, if relative humidity is more than 80% and if temperature is below 25 degrees celsius, tea is strongly susceptible to Blister Blight fungal disease which reduces the crop by 30%–40%. The susceptibility of tea plants to Nematodes such as P. Loosi which invade roots within 48 hours after planting and dry weather pests like Tea Tortrix and fungal diseases like Blister Blight during high humidity seasons are significant challenges in plantations.

Currently, only very limited and a few contact and systemic fungicides are permitted to be used for control of pests and diseases because of MRL requirement by buyers. However, well distributed annual monsoonal rainfall patterns, accompanied by high humidity and tropical high temperature, humid climatic regime easily pre-dispose tea plants to many pests and diseases and provides a very conducive ecological platform for pests and disease attacks on tea.

Climate change impact

Vapour Pressure Deficit (VPD) determines productivity of tea. During dry months and low vapour pressure deficits with low relative humidity, resulting in high transpiration and desiccation; pre drought foliar spraying of potassium sulphate is required to protect the bush and maintain crop physiology. High vapour pressure deficit periods with high relative humidity encourage rapid spread of fungal diseases that require prophylactic spraying of copper fungicides.

[Dr. Roshan Rajadurai is the Managing Director of the Plantation Sector of Hayleys PLC (which comprises Kelani Valley Plantations, Talawakelle Tea Estates and Horana Plantations). A former Chairman of the Planters’ Association of Ceylon, Dr. Rajadurai has 36 years of experience in the plantation sector.]