Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Wednesday, 9 January 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is a wrong premise to argue that to encourage the private sector and the market, the public sector and the Government have to step-back, and get involved only in necessary reforms and encouragement. This is the main thrust of ‘Vision 2025’. In this kind of a reductionist vision even the State will be at risk.

It is both theoretically and practically possible to encourage the private sector (particularly the SMEs) and the market, while the public sector is preserved and strengthened to deliver all public services (education, health, welfare, pensions, age care, etc.) and undertake large scale enterprises (i.e. ports, airports, shipping, power, energy, airlines), and any other, to make the public sector sustainable and economically strong. There are other sectors like customs that can be profitable naturally for the public sector.

Strengthening the ‘public sector and/or the private sector’ in the economy should not be considered a zero-sum game. It should not be one against the other or one verses the other. When one grows, the other should not shrink. When one is supported, the other should not be discarded. All these are misconceptions or misplaced policies. What is necessary is a generally agreed division of labour between the two, with adjustments in the course of the implementation.

Three layers or circles

The State is of primary importance in both society and economy. Four main components of the state are ‘territory, people, government and administrative (including military) structure,’ all protected through State sovereignty. People are organised in society. Economy is their means of survival and progress.

The demarcations between the State and society are well explained and established in democratic theory. But the demarcations between the State and economy have always been a controversy. The reasons are mainly class or unequal economic power in society.

No state exists in isolation, but within a sea of other states which makes the above matter more complicated. However, the application of democratic theory and people’s sovereignty to the economy should be able to resolve this controversy.

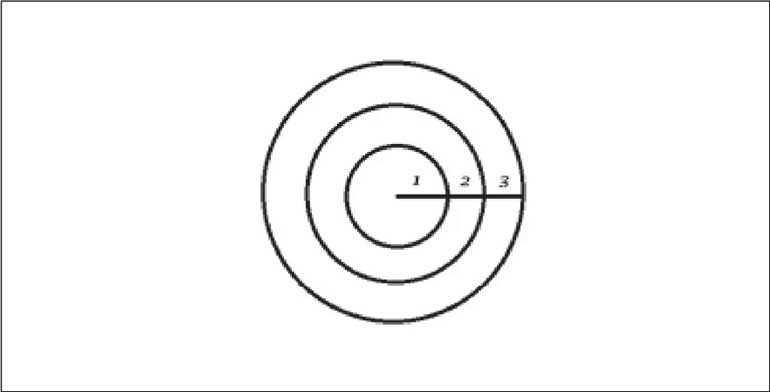

The simple figure 1 of three concentric circles roughly explains how these relationships could be maintained particularly in the case of Sri Lanka. Circle 1 is for the State structure, Circle 2 for the public sector and Circle 3 for the private sector.

The middle circle is introduced to the figure to emphasise the importance of the State and its leadership in the economy. One of the recent brilliant books on the subject is by Marina Mazzucato titled ‘The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths’ (2018). Based on neoliberal or archaic liberal thinking, there are efforts in Sri Lanka and elsewhere to reduce or even dismantle the state and/or state structures/functions. Similarly, there can be authoritarian thinking geared to control and subjugate the economy, entrepreneurs and businesses in a bureaucratic manner to control the economy for different interests.

A balanced and a rational approach would be to allow the third circle or the private sector to grow as much as possible while the second circle is strengthened and expanded to serve not only all necessary public services but also to ensure that sector’s and the state’s economic sustainability. The state (or the first circle) can be entrepreneurial as Mazzucato has explained. That kind of an approach would address underdevelopment, poverty, imbalances between regions, agricultural neglect, environmental problems and natural disasters.

Need for two engines

There are three main reasons why the public sector/State should be strengthened at present. (1) Since 1977, the public sector has been neglected and distorted. (2) A vibrant public sector is necessary to ensure basic needs, economic and social (human) rights, and to eradicate poverty. (3) Looking after the public sector is a major task of representative democracy. Otherwise, what is the purpose of a democratic state?

However, none of the above should preclude an equal or important role for the private sector. Once a core functions are secured for and undertaken by the public sector like education, health, social security, old age pension, infrastructure, ports and airports, energy supply, and in my opinion main transport (rail and bus), many of the other sectors can be left for the private sector. They can be unlimited.

What can they be? They can be heavy industries (vehicles, appliances, machinery), IT, wholesale and retail trade, food production, agricultural products, apparel, imports and exports, tourism, pharmaceuticals, etc. Of course there is no need to produce them all locally as some of them could be easily and cheaply imported. However, there can be certain areas where the country could develop some expertise in industrial production for exports.

There are of course other essential state functions that even the most ‘liberal’ state would undertake like national security, law and order, justice, death and birth certificates, customs, etc. Then there are other areas that both sectors could do or undertake jointly or parallelly. Here we are talking about the tasks that are important for economic growth, services and functions. Some of these are banking, tourism, IT, pharmaceuticals, the media or any other areas agreed through policy discussions.

What is importance to have is a two-engine ‘train’ for economic development. Because the country’s development is an up-hill task. Believing or depending on one engine is a mistaken or erroneous policy. (My imagination goes back to childhood holiday travel to hill country where we were eagerly awaiting to reach Rambukkana to see the second engine is fixed to the back of the train by engine drivers! Can our political engine drivers learn something from that experience?).

Past experience

Sri Lanka in fact inherited a fair balance between the two sectors at independence thanks to the British Labour Party influence in colonial policies and the pressure of the labour/left movement in the country (both in the urban and plantation sectors). However there were efforts from the beginning to dismantle what could be called a Welfare State. Apart from disenfranchising the plantation workers in 1948, an attempt was made in 1953 to cutdown the rice ration, signalling the trend. From the beginning, political leaders did not have a clear or a balance economic policy to develop the country. Otherwise, keeping the Welfare State intact, both the private sector and State enterprises could have been developed in the economy. Although there were no proper welfare states in East or Southeast Asian countries, the ‘two-engine’ growth was what those countries implemented during that period. That is how they progressed well ahead of Sri Lanka.

The absence of progress and development thereafter tempted the second generation political leaders to largely depend on the State sector. There were other reasons like nationalism, left movement’s influence and Soviet example that generated this trend. Then became the unbridled market economics dismantling the welfare state since 1977, with variations under different leaders (JR, Premadasa, Chandrika and Rajapaksa). The State sector was kept for political reasons, mainly to give employment for party supporters. This kind of a State sector undoubtedly is a liability to the economy.

Present situation

There is no question that the present UNP leadership has been attempting a different strategy. The following is what the Vision 2025 declares in terms of economic strategy (p. 16).

“The private sector will play a key role: achieving high productivity, innovating, enhancing quality, as well as investing and creating new jobs. The Government will coordinate with the private sector to make the economy competitive and successful in the global environment. With market principles, economic competitiveness and social benefit in mind, we will drive appropriate economic and social policies and strategies to ensure prosperity for present and future generations.”

“The Government is undertaking macroeconomic, factor market, institutional and regulatory reforms to enhance the productivity and competitiveness of the economy. These reforms are expected to raise private investment, especially knowledge-intensive and technology-driven FDI for export growth in both goods and services.”

Private sector is the declared (sole) engine of growth in the Vision and expressed in policy statements. No mention of the public sector as part of the main strategy. Private sector is defined more in an international context than in a national dimension. Complete external dependence is one hallmark through free trade agreements and other means. Another attempt is to reduce the State and the public sector to barebones.

Under such circumstances the declared ‘vision to make Sri Lanka a rich country by 2025’ (p. 11) appears wishful thinking. The Vision also declares ‘to raise per capita income to USD 5,000 per year’! (p. 13) without any foundation. The Vision 2025 cannot at all be considered a realistic economic blue print or plan by any means under the circumstances.

For the economic failures so far, four main reasons can be attributed. (1) Inherent contradictions and weaknesses of the one-engine growth strategy and extreme neoliberalism. (2) Political contradictions within the UNP-SLFP coalition, and its disintegration. (3) Contradictions and uncertainty within the UNP itself over the economic policy or business vs welfare. (3) The futile attempt to follow an extreme neoliberal policy when the world was moving away from that ideology and practice.

Conclusion

Because of the failure to have a democratic approach on the economic policy after the January 2015 political change (giving equal priority to both the private and the public sectors), the current economic situation is in dire circumstances.

Agricultural sector, local businesses and what can be called the ‘national economy’ have been neglected. The Government has not given any priority for poverty alleviation, and has tried to hide the situation through an erroneous Official Poverty Line (OPL).

There is no question that strengthening and resurrecting the public sector is not an easy task. A major reason is that it has continuously been used for political appointments and employment. One solution might be to use a suitable business (or organisational) excellence framework for reforming it. There are several of them in the world and in Australia it is the Australian Business Excellence Framework (ABEF). More important is to have a common strategy to develop and assist both sectors, the State taking an entrepreneurial leadership. The necessary vision should be a two-engine growth and development.