Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Wednesday, 5 July 2023 00:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

President Ranil Wickremesinghe

Former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa

“What causes do we not invent for the misfortunes that befall us? On what do we not place the blame, rightly or wrongly, so as to have something at which to strike?”

– Montaigne (Essays)

BY Tisaranee Gunasekara

The question was simple: how the candidate was going to fund the many and extravagant election promises, considering the already high debt burden.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa seemed to be listening intently. He nodded, turned his head to the right then to the left, played with a pen, leaned back and leaned forward. Behind the spectacles, his eyes regarded the world with bemusement. When the questioner asked about the candidate’s links with the international community, Rajapaksa touched his forehead.

When the question ended, he sat back and pointed a finger at his elder brother.

Mahinda Rajapaksa’s answer was as relevant as a summer dress in the Russian winter. He talked about 2005, how everyone predicted bankruptcy and yet, he proved them wrong. Money would be no problem, he indicated.

There were no follow up questions.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s inability to understand the ABC of economics would have been obvious to any clear-eyed voter who watched his only encounter with the media as the newly burnished presidential candidate of Rajapaksa Inc. Intoxicated by dreams of majoritarian supremacy and quick-fix development, most Sinhalese allowed themselves to be fooled.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s inability to understand the ABC of economics would have been obvious to any clear-eyed voter who watched his only encounter with the media as the newly burnished presidential candidate of Rajapaksa Inc. Intoxicated by dreams of majoritarian supremacy and quick-fix development, most Sinhalese allowed themselves to be fooled.

The greatest hoax of modern Lankan politics was not the work of the Rajapaksas alone. They couldn’t have carried it off without scores of others – politicians, business and cultural leaders, Buddhist monks and the Cardinal, media moguls and journalists. All of them colluded with the Family in dressing up a firefly as a bright new sun. They were in the know, had to be in the know, unless their understanding was more deficient than the Candidate’s.

These vested interests didn’t stop at helping elect the worst president in Lankan history. They backed him with strategic words and even more strategic silences as he, a politico-economic babe-in-the-woods, led the country to the abyss of bankruptcy, step by preventable step. It was only when they realised that their own survival depended on taking a stance against the Rajapaksas, that some of them jumped ship.

In the early years of Donald Trump, when many an anti-Trumper chose to believe Ivanka Trump’s carefully crafted liberal-feminist image, Saturday Night Live did a skit of a perfume advertisement – Complicit, a fragrance for the woman ‘who knows what she wants and knows what she’s doing, who could stop all this but won’t’. Lanka might have evaded ruin, if G.L. Peiris, Dullas Alahapperuma, Wimal Weerawansa, and Udaya Gammanpila opposed the organic fiasco in the cabinet, if Nalaka Godahewa, Charitha Herath, and Channa Jayasumana explained the dangers of excessive money-printing at Viyath Maga gatherings, if the political monks compelled the president to address the growing public distress. None of them did so. Like the woman in that SNL skit, they knew what they wanted and knew what they were doing. They too were complicit.

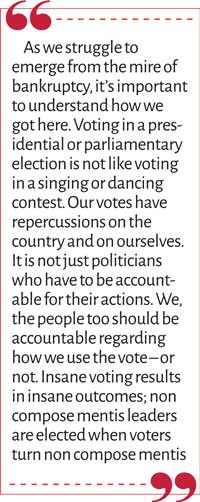

As we struggle to emerge from the mire of bankruptcy, it’s important to understand how we got here. Voting in a presidential or parliamentary election is not like voting in a singing or dancing contest. Our votes have repercussions on the country and on ourselves. It is not just politicians who have to be accountable for their actions. We, the people too should be accountable regarding how we use the vote – or not. Insane voting results in insane outcomes; non compose mentis leaders are elected when voters turn non compose mentis.

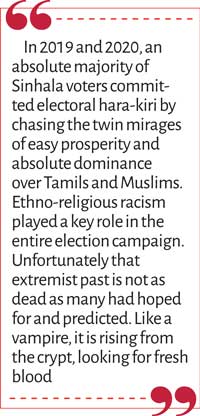

In 2019 and 2020, an absolute majority of Sinhala voters committed electoral hara-kiri by chasing the twin mirages of easy prosperity and absolute dominance over Tamils and Muslims. Ethno-religious racism played a key role in the entire election campaign. Unfortunately that extremist past is not as dead as many had hoped for and predicted. Like a vampire, it is rising from the crypt, looking for fresh blood.

Dreams and nightmares of yesteryear

On this day one year ago, 5 July 2022, a 60-year old man died in the petrol queue at the OIC station in Borella. His was the 14th death in a petrol queue. On this day one year ago, activists at Gota-go-gama gave President Gotabaya Rajapaksa an ultimatum. Leave by 9 July or you will be made to leave.

On this day one year ago, 5 July 2022, a 60-year old man died in the petrol queue at the OIC station in Borella. His was the 14th death in a petrol queue. On this day one year ago, activists at Gota-go-gama gave President Gotabaya Rajapaksa an ultimatum. Leave by 9 July or you will be made to leave.

President Ranil Wickremesinghe recently gave his own version of the tumultuous events of last July. “...as we began to recover, a wave of protests emerged. On July 9, a group of organisers managed to gather a significant number of people in Colombo, something unprecedented in scale.”

He was right about the unprecedented part, wrong about the rest. The number of people who turned up on 9 July to send Gota home was unprecedented because the crisis was unprecedented. There was no recovery in sight; normal life remained broken. The Rajapaksas were plotting a full comeback, with brand new parliamentarian Dhammika Perera demanding Wickremesinghe’s resignation as finance minister and accusing him of ‘planning for disaster’. Most Lankans understood that their suffering could not end so long as Gotabaya Rajapaksa was at the helm. That was why close to a million people descended on Colombo on 9 July and not even a thousand did on subsequent occasions when the same organisers tried to get another Aragalaya going against President Wickremesinghe.

People wanted queues to end, for life to return to some kind of normalcy. President Wickremesinghe managed that. Now the task is to ensure a just recovery from the crisis, a truly daunting challenge with no easy solutions or quick fixes. According to a new survey by LIRNEAsia, 31% of Lankans now subsist below the poverty line, 7 million people. 32% of families have sold their household assets to make ends meet (such as refrigerators and motorcycles). 50% have dipped into their savings for daily expenses. This is not just an economic crisis but a human tragedy with the potential to undermine health, education, and wellbeing of several generations.

Aswesuma is a better response to this catastrophic situation than Samurdhi. Even in this country where politicisation is the norm, Samurdhi was exceptional in its blatant political weaponisation. Samurdhi officials function like employees of a mega SOE, focused on their rights and continued existence rather than on poverty alleviation. Again, according to the LIRNEAsia survey, only 31% of the poorest income decile was covered by Samurdhi. Samurdhi recipients included people belonging to every income decile including 4% of the richest 10%. (Ranasinghe Premadasa’s Janasaviya, like Aswesuma, was a time-bound program and not an open-ended one like Samurdhi. Nor was Janasaviya politicised to the same level as Samurdhi. The difference was both quantitative and qualitative.)

Aswesuma would provide Rs. 15,000 per month for three years for 400,000 extremely poor families and Rs. 8,500 per month for three years for 800,000 poor families. 400,000 vulnerable families and 400,000 families in transitional state will receive Rs. 5,000 and Rs. 2,500 for shorter time periods. As Gayani Hurulle of LIRNEAsia pointed out, these 2 million Aswesuma recipient families cover the 7 million people identified as poor. But for these families to escape poverty cash transfers alone will not suffice. They will also need access to credit facilities and to technical training and marketing advice. If not, many of them will fall prey to the predatory micro-finance mafia. (Incorporating a streamlined Samurdhi Bank into the Aswesuma programme could be one answer.)

The Opposition, instead of mindlessly opposing Aswesuma and supporting the irretrievably flawed Samurdhi, should come up with concrete proposals of how best to deal with the poverty time-bomb. Just as it should engage with the Domestic Debt Restructuring (DDR) program to ensure that the burden on ordinary people is minimised.

Ideally, the EPF and the ETF should have been kept out of the DDR process. But their inclusion is unlikely to impact deleteriously on members if the interest rates promised by the Government are legislated, as parliamentarian Harsha de Silva has proposed. According to the DDR program, EPF members are guaranteed a minimum interest of 12% until 2025 and an interest of 9% afterwards. In 2018 and in 2019, before the return of Cyclone Rajapaksa, the EPF paid an interest rate of 9.5% and 9.25% respectively.

In 2020, 2021, and 2022, the interest rate was 9% (despite the much higher rate given to bank deposits). So members will not suffer a financial loss, if the promised minimum rates are delivered and measures are taken to safeguard emergency medical support offered by the ETF. (Incidentally, contrary to a popular myth, most countries do tax pension funds, usually at a concessionary rate).

In 2020, 2021, and 2022, the interest rate was 9% (despite the much higher rate given to bank deposits). So members will not suffer a financial loss, if the promised minimum rates are delivered and measures are taken to safeguard emergency medical support offered by the ETF. (Incidentally, contrary to a popular myth, most countries do tax pension funds, usually at a concessionary rate).

The hysteria about EPF has meant that no attention is paid to the main component of the DDR: subjecting locally issued dollar denominated bonds to principal haircuts and interest rate reductions. Possibly because that measure impacts on the very rich – the minimum bid is $ 10,000 – including Lankan nationals with dollar accounts.

At a recent investment conference held in London’s iconic Savoy ballroom, a group of global plutocrats and their financial advisers were told that unless they use their millions to help economically struggling families, “they may soon need to watch out for people with pitchforks and torches.” This is a warning Lankan political and business leaders too should take seriously. By building a palliative care centre for children with cancer in memory of his daughter, Karu Jayasuriya has provided an example. Similar interventions in health, education, and poverty alleviation can prevent a worse July. If compassion is absent, look to self-interest. Instability is bad for business.

Change for better, change for worse

Change was a major promise of Gotabaya Rajapaksa. And he delivered in spades. The country he fled from in 2022 was radically changed from the country he took over in 2019.

According to recent opinion polls, if there’s an election today, the JVP, while falling short of an outright majority, will emerge first. Given the degree of the JVP’s economic incognisance, a JVP/NPP administration will indeed usher in a tsunami of change. Economic fundamentals matter. 6.9 million voters ignored Rajapaksa’s economic incomprehension at their peril. There’s no reason to think that a better outcome will occur if they similarly ignore the JVP’s simplistic ideas of how economies work.

An SJB government too will usher in its own brand of change, as is evident from its formation of a Bhikkhu Advisory Council. Sajith Premadasa seems to be modelling himself on SWRD Bandaranaike and Gotabaya Rajapaksa rather than his father who didn’t need or want monks telling him how to govern (his priority was houses and factories not 1,000 chaithyas)

There are many Lankan monks who either focus on becoming stream-enterers or on non-politicised social work. (An excellent example of the latter is Henegedara Dhammadara thero who runs Suwamansala, a palliative centre in Maharagama providing food, lodging, medicine, and other facilities to about 100 cancer patients of all races and faiths and their carers – youtube.com/watch?v=uqr3InHL1TE). But such monks, like the Buddha, do not go after politicians. Any advisory council will, by definition, be filled not with such monks but with political monks who shamelessly abuse the saffron robe to gain a slice of power.

A luminary of the SJB’s monk advisory council is Agalakada Sirisumana thero who, during an anti-devolution demonstration this year, threatened to ‘throw out’ any leader who tries to implement the 13th Amendment. What will the SJB do with his advice?

Will the SJB give into a demand common to all political monks and introduce a blasphemy law, creating many more Shakthika Sathkumaras and Nathasha Edirisooriyas (who is still languishing in jail while others who made far more ‘problematic’ statements, from Akmeemana Dayarathana thero to Dilith Jayaweera, remain free)?

Whether Ranil Wickremesinghe, given his dependence on the military top brass, will actually follow up on his promise and reduce defence expenditure remains to be seen. Can the SJB, given its wooing of political monks, and the JVP, given its wooing of retired military personnel, do better? Will either party have the courage to stand up to the insidious campaign by political monks to use the historical heritage issue to spark an anti-Tamil/Muslim unrest or use the religious conversion issue to pit Buddhists against Christians? What does SJB’s monk advisory council feel about the plan by some of their brethren to build a temple on every mountaintop?

Whether Ranil Wickremesinghe, given his dependence on the military top brass, will actually follow up on his promise and reduce defence expenditure remains to be seen. Can the SJB, given its wooing of political monks, and the JVP, given its wooing of retired military personnel, do better? Will either party have the courage to stand up to the insidious campaign by political monks to use the historical heritage issue to spark an anti-Tamil/Muslim unrest or use the religious conversion issue to pit Buddhists against Christians? What does SJB’s monk advisory council feel about the plan by some of their brethren to build a temple on every mountaintop?

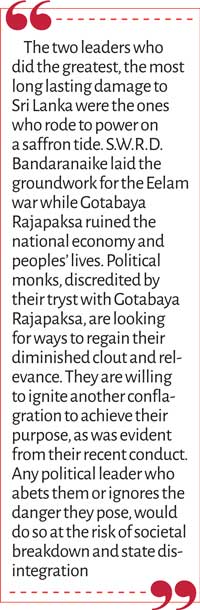

The two leaders who did the greatest, the most long lasting damage to Sri Lanka were the ones who rode to power on a saffron tide. S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike laid the groundwork for the Eelam war while Gotabaya Rajapaksa ruined the national economy and peoples’ lives. Political monks, discredited by their tryst with Gotabaya Rajapaksa, are looking for ways to regain their diminished clout and relevance. They are willing to ignite another conflagration to achieve their purpose, as was evident from their recent conduct. Any political leader who abets them or ignores the danger they pose, would do so at the risk of societal breakdown and state disintegration.

“A soul anxious about the future is most vulnerable,” warned Seneca. We live in a time where anxiety about the future is a national condition.

That anxiety makes us vulnerable to non compos mentis appeals and their purveyors, if not today then some tomorrow.