Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Thursday, 28 April 2022 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

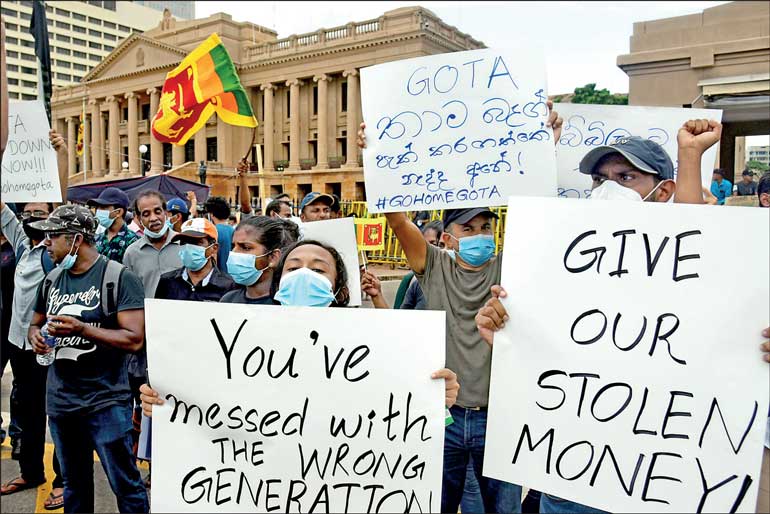

The dynamism and reach of the struggle to oust President Gotabaya is such that Rajapaksa rule cannot hold the line for much longer

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, or Gota as the world now knows him from Northern Ireland to New Zealand and Australia to America, thinks the Presidency is something he owns. The real owners who lent it to him—the sovereign citizenry—want it back because he has put it to such terrible use.

lent it to him—the sovereign citizenry—want it back because he has put it to such terrible use.

President Gotabaya must know that he cannot rule without the consent of any social class or category of the citizenry from the apex of the social pyramid to its base. If GR doesn’t leave voluntarily, the collective emotions involved will make the citizens rebel more widely, determinedly, forcefully and irresistibly against him.

Are the people of all classes and generations, led by the youth, justified in insisting that ‘Gota gotta go’? Yes, not only for the bare-faced unilateral abrogation of the Social Contract but for reasons of social psychology far deeper than any constitutional niceties. On Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s watch Sri Lanka is not only begging from neighbours but is the beneficiary of charity bestowed by a generous mendicant in India and primary schoolkids in China.

Any Sri Lankan with a sense of dignity would want Gotabaya Rajapaksa who actively contributed to this unprecedented humiliation, gone as fast as possible. Future generations must know that the generations living now, did not accept this humiliation passively, they mobilised and actively turfed out the ruler. He must be tossed overboard because the message must go out to the world and to future generations that we did not put up with this lowering into the abyss and threw out the ruler responsible.

“A single spark can start a prairie fire” said Mao Zedong. Anything could spark off a nationwide riot, an uprising of the people, that would wreck the economy beyond anything the IMF could rescue. That would be the ultimate landscape of anarchy. The prospect can be averted only by the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. If he fails to do so soon enough and the rioting starts—almost certainly due to economic scarcities or state suppression or both—history will judge GR as the foremost Father of Anarchy.

Addressing SLPP MPs and PC members on 26 April, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa absurdly attributed, the Galle Face agitation to those who had wanted revenge from the Rajapaksas for having won the war. If Dulles Alahapperuma or Susil Premjayanth were to take over as PM, repealing the 20th Amendment and rushing through a retooled 19th Amendment, there would be an immediate retardation of the galloping growth of the confrontation. Refusing to resign though he has manifestly lost the confidence of the public, Mahinda Rajapaksa is another Father of Anarchy.

attributed, the Galle Face agitation to those who had wanted revenge from the Rajapaksas for having won the war. If Dulles Alahapperuma or Susil Premjayanth were to take over as PM, repealing the 20th Amendment and rushing through a retooled 19th Amendment, there would be an immediate retardation of the galloping growth of the confrontation. Refusing to resign though he has manifestly lost the confidence of the public, Mahinda Rajapaksa is another Father of Anarchy.

Anarchic abolition agenda

The Aragalaya (the Struggle) strives, in the first place, to remove the malignant tumour of the Rajapaksa oligarchy from the body politic.

The task of the political parties is to reflect and facilitate the achievement of the primary Aragalaya aim or at least the closest approximation of that aim, in the shortest possible time.

Their task is ‘not’ to delay and divert the achievement of the Aragalaya aims and agenda by overshooting the mark or diverting energies to the achievement of the old ideological agendas of the political parties themselves. Targeting 20A would be an accurate mirroring of the slogans of the Struggle.

The attempt to remove the executive presidency at this point requires a protracted Supreme Court proceeding, a Referendum campaign and a Referendum. This is a delay and diversion that entrenches the 20th Amendment with Gotabaya’s untrammelled control over the State machine, and buys the Gotabaya presidency many months more.

Good sense dictates an amendment to amputate President GR’s (or any President’s) powers, which can quickly obtain a two-thirds majority, rather than raise the bar up to abolition of the executive presidency, which could block any agreement at all, even of the entire Opposition, let alone of the Opposition and dissidents within the Government.

Every day that the Opposition delays the task of divesting President Gotabaya Rajapaksa of a decisive measure of power, the more it contributes to the probability of anarchy with its fatal effect on the economy.

The political Establishment – the mainstream political leadership embracing Government and Opposition—seems to have no sense that there’s a clock ticking on their role and relevance.

Already a situation of Dual Power (Lenin’s famous term) has arisen: the System vs. the Streets. Collective social energy outside Parliament is driving Sri Lankan processes and developments today. The leading ideas, slogans and political agenda are powered by and through networks of the youth, the community and the working people, and not through the institutional framework of the state (including the Parliament).

The Government and the Opposition are being bypassed by the young, the people at large, and the country as a whole. The centre of gravity of the Sri Lankan sociopolitical process, indeed of current Sri Lankan history, has bypassed the political establishment, its institutions, and its personalities. Both wings of the Opposition, SJB and G-40, should and can produce an effective two-thirds majority for a quick political intervention, out-running the crisis.

quick political intervention, out-running the crisis.

At this inflection point in history the main strategic responsibility the Opposition is to form the broadest possible political coalition against the autocrat so as to oust him. That cannot be done by taking at this moment, the position that the executive presidency itself be destroyed. That was not the strategy of all known struggles, however radical or diverse their methods, to defeat autocrats from Batista to Somoza, Marcos to Pinochet.

The more clearly defined, modest and narrower the target and program, the broader the unity. The broader and more ambitious the target or program, the narrower the unity. The broader the unity, the surer the victory.

In an interview given to a Sunday newspaper, TNA parliamentarian M.A. Sumanthiran discloses that he co-authored the SJB’s 21st Amendment:

“Our policy has always been that the Executive Presidency must be abolished. Not as the TNA but as a lawyer I have been involved in the process of drafting the 21st Amendment they are introducing today (21 April) to abolish the Executive Presidency in full. … When I met him [the Prime Minister] yesterday, my advice was that the Executive Presidency must be abolished in toto and that if it requires a referendum, in the current context the people will definitely grant that approval.”

The abolition of the executive presidency is a protracted process requiring a referendum at a moment of extreme crisis in which time is the one thing the country does not have.

Sumanthiran sees the repeal of the 20th Amendment as of no value and the abolition of the executive presidency as the only truly worthwhile aim and imperative.

“…It will not grant solutions to the current problem. Even for political stability I don’t think it is going to do much, because it just takes away some of the President’s powers, which have to be shared with the Prime Minister. Again it’s just a family affair. That’s not going to solve the current issues.”

This argument is ridiculous because Constitutional reform is not predicated on who holds the post of President and/or PM, but on the interface of soundness of architecture and urgency of reform.

Given that Sumanthiran is a frank, full-blooded federalist who wishes to “go beyond the 13th Amendment”, it is also unsurprising that the draft of the 21st Amendment he co-authored paves the way for such an outcome as a by-product. It advocates the abolition of the executive presidency directly elected by the whole island, which if accomplished, springs the 13th Amendment from the parametric limits of the unitary state, in effect turning it federal.

This would turn any referendum into a real battleground between liberal democracy and Sinhala nationalism, and even if the former wins, Sri Lanka would become what it was in 2015-2019, an ideologically divided nation like the USA is today. It would reinstate a schism that has been transcended by the Aragalaya.

Already the SJB’s chairman, Field Marshal Sarath Fonseka has sounded a dissentient note in Parliament against the abolition of the executive presidency. The significance of his dissent is that it may be taken as a representative reflex-action of the wartime Sri Lankan military.

Any serious student of politics and contemporary history would know that a crucial threat at this moment is a military-led counterrevolution: the Myanmar model. For that worst-case scenario to be triggered there has to be what is known as a ‘coup consensus’, by which is meant a consensus within the officer corps. Such a consensus is not pre-existing or, in Lanka’s case unlike Pakistan’s and Myanmar’s, a predisposition. Here it would take lobbying and persuasion.

The democratic movement must try incessantly to swing the needle of military deliberation in the direction of non-intervention. This requires steering clear of the military’s red-lines which as in case of laser-beams in alarm systems, tend to be invisible to the naked eye. One of the redlines is a weakening of the state in general, and the gains of a war that has been won in particular.

direction of non-intervention. This requires steering clear of the military’s red-lines which as in case of laser-beams in alarm systems, tend to be invisible to the naked eye. One of the redlines is a weakening of the state in general, and the gains of a war that has been won in particular.

The SLFP-led 11 parties’ Group of 40 (G-40) contains a number of very experienced politicians, including a former President. It can quickly change the nation’s situation for the better by presenting a platform or initiative that can flip a sufficient number of SLPP members to crash the Rajapaksa-led ruling party’s parliamentary majority.

As the SLFP General Secretary Dayasiri Jayasekara stressed, the abolition of the executive presidential system in the presence of the Provincial Councils makes for de facto federalism and centrifugal pressures. Furthermore, given the system of proportional representation, it makes for an unstable parliament.

The retention of the executive presidency shorn of its autocratic powers conferred by the 20th Amendment would be a modest price to pay for the preservation of the PCs and PR.

Myopia and political strategy

According to respected columnist and blogger D.B.S. Jeyaraj, the main Opposition’s decision to adopt the abolition slogan, which he says came as a surprise, can be precisely sourced to a 6 April conclave convened by Sumanthiran.

“Now a third meeting was held on 6 April to discuss the ongoing political crisis. Several political party leaders and MPs participated in a four-hour meeting from 5:30 p.m. to 9:30 p.m. at the ‘Monarch Imperial Hotel’ in Kotte. Among those who attended the meeting were Opposition and SJB Leader Sajith Premadasa, UNP Leader and former PM Ranil Wickremesinghe, former Speaker Karu Jayasuriya, Muslim Congress Leader and MP Rauff Hakeem, TPA leader and MP Mano Ganeshan, Former Ministers and SJB MPs Eran Wickremaratne and Dr. Harsha de Silva.”

That meeting concluded: “...The best way…is to abolish the executive presidency itself. The Sri Lankan people would gladly welcome the disempowerment of the ruling executive president by abolishing the executive presidency...”

The abolition agenda clogs up Oppositional consensus in Parliament at a time when the ability to build bridges in the Opposition is a skill of paramount importance. What is the point in advertising the ability to build ‘bridges not walls with the international community’ if one builds walls not bridges within the Opposition in Parliament?

The 6.9 million may not agree with the slogan of abolishing the executive presidency instead of simply repealing 20A. Therefore, a slim yet significant enough percentage to make a difference at an election may opt for the SLFP-led coalition, in a stiff contest between the SJB and the JVP-NPP.

The slogan of the abolition of the executive presidency at the top of the 21st Amendment makes that version of the amendment as proposed by the main Opposition alliance, a reactivation of the draft documents of the ultra-liberal Constitution presented in 2015-2019 by Ranil Wickremesinghe and Mangala Samaraweera’s UNP; an ideological position which added to the rift with the SLFP in the Yahapalanaya coalition.

The greater the continuity with that project, the greater the embedding of the new SJB in the old Ranil-Mangala UNP ideological enclave—which delimits and limits its electoral appeal. This pivot—or natural return perhaps—to the liberal centre-right on both constitutional and economic policy means that the centre-left space is open for occupation by the SLFP-led bloc, and the left space by the JVP-NPP.

The abolition of the executive presidency slogan makes for strategic nonsense when one factors in that Sajith Premadasa proved himself in 2019 far more popular than the UNP in 2018 and SJB in 2020. Even being the legatee of President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s socioeconomic programs of rapid industrialisation and social upliftment, any scrapping of the presidency or a pledge to do so would wipe out the advantage of being able to credibly pledge continuity with that developmental model and those programs.

Given its recent pivot to a policy package on a continuum with the Ranil Wickremesinghe UNP of 2001-2004 and 2015-2019, the SJB as the next governing party may similarly have a vulnerable majority on its own and a no less vulnerable coalition with the TNA.

If the parliamentary deadlock continues due to the sudden evangelical conversion of the main Opposition party to liberal constitutional maximalism, there can be only one result: the 20th Amendment stays, and it stays in Gotabaya’s hands, making inevitable a violent clash between the Street and the State, disintegrating and destroying the economy completely.

The future of democracy and the system—including the parliamentary system—depends in this revolutionary time, on the ability of the SJB to form an alliance or at least a working relationship with the SLFP, thereby constituting a strong Centre on a new Middle Path. The slogan of the abolition of the executive presidency instead of reforming it, sabotages that strategic imperative.

The struggle goes on

Like the previous landmarks of the Aragalaya (Struggle) such as Mirihana 31 March, the defiance of 3 April, the Galle Face gathering of 9 April and the inspirational communications triumph of the naming of GotaGoGama, the dramatic demonstration by the Inter-University Students Federation (IUSF) of 24 April led by the irrepressibly gutsy Wasantha Mudalige was an important marker in the evolution of the balance of forces on the ground.

The dynamism and reach of the struggle to oust President Gotabaya is such that Rajapaksa rule cannot hold the line for much longer. The Rajapaksas no longer have their traditional support base to fall back on: the rural heartland with its Sinhala Buddhist peasantry. That historic safe-zone was nuked by Gotabaya’s fertiliser ban.

Before this story is over, President GR and his elder brother, Prime Minister MR, will realise that it is one thing to have fought and beaten the LTTE, an armed minority of a minority, and quite another to fight the vast majority including in the Deep South.

They will learn from experience that there is no force on this island that’s stronger, more powerful than the Will of the People.

Until the Rajapaksas led by Gotabaya leave, the famous slogan of the African liberation fighters of Angola retains its relevance: “A Luta Continua!” (“The Struggle Continues!”)