Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 10 November 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution of Sri Lanka created the Provincial Councils andset out the powers, duties and responsibilities of such Councils. That ConstitutionalAmendment also distinguished between the functions of the Provincial Councils (set out in List I–“Provincial List” of the Ninth Schedule to the Constitution) with that of the functions of the Central Government(set out in List II–“Reserved List” of the Ninth Schedule). A further List III– “Concurrent list” set out the functions where the responsibilities were to be shared between the two layers of government.

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution of Sri Lanka created the Provincial Councils andset out the powers, duties and responsibilities of such Councils. That ConstitutionalAmendment also distinguished between the functions of the Provincial Councils (set out in List I–“Provincial List” of the Ninth Schedule to the Constitution) with that of the functions of the Central Government(set out in List II–“Reserved List” of the Ninth Schedule). A further List III– “Concurrent list” set out the functions where the responsibilities were to be shared between the two layers of government.

Some of thefunctions where the Provincial Councils share responsibility with the Central Government (as per the  Concurrent List),as well as those where the Provincial Councilsbear total responsibility (as per the Provincial List), include the following:Finance and Planning; Education; Food supplies & distribution; Fisheries; Employment; Tourism; Irrigation; Agricultural and agrarian services; Rural development; Health; Housing and construction; Roads and bridges; Social service and rehabilitation; Animal husbandry; and Road passenger carriage services.

Concurrent List),as well as those where the Provincial Councilsbear total responsibility (as per the Provincial List), include the following:Finance and Planning; Education; Food supplies & distribution; Fisheries; Employment; Tourism; Irrigation; Agricultural and agrarian services; Rural development; Health; Housing and construction; Roads and bridges; Social service and rehabilitation; Animal husbandry; and Road passenger carriage services.

Further, theLocal Government institutions, (previously 336,and now 341)namely, the Municipal Councils, Urban Councils and Pradeshiya Sabhas in the Provinces also function under the respective Provincial Councils. Accordingly, a massive quantum of work which has a direct and close bearing to the well-being and day-to-day lives of the people is carried out by these Provincial Councils and Local Government authorities.

As may be expected, such wide-spread and “people-related” functions require a sizeable quantum of funds and therefore the allocation and appropriation of such fundshas beenlegally covered in Section 19 of the Provincial Councils Act No 42 of 1987. Sub-section 1 of that Section specifies that the required funds are to be raised via the proceeds of taxes imposed by the Provincial Councils, grants by the Government, loans advanced from the Consolidated Fund, andother receipts of the Provincial Council.

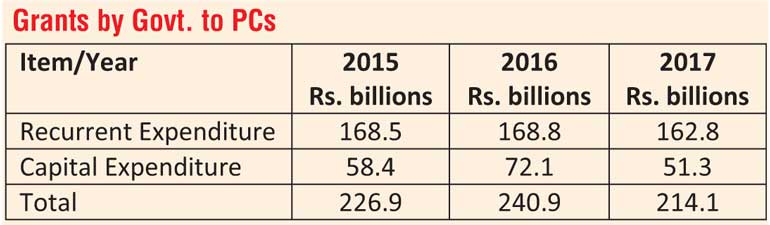

Over the years, the grants by the Central Government to the Provincial Councils have been substantial, and as per the Ministry of Finance data, sums these are set out in the Table. In addition, each of the Provincial Councils has also raised funds through its own taxes and receipts.

The appropriations and withdrawals from the Provincial Fundare dealt with inSub-sections (2) (3) and (4) of Section 19of the Provincial Councils Act, which providesthe legal basis for expenditure to supportthe functions and workings of the Provincial Councils. These legal provisions specify that fundsshall not be appropriated out of the Provincial Fund of a Province “except in accordance with and for the purposes and in the manner provided in the Act”; and further that“no sum shall be withdrawn from the Provincial Fund except under a warrant under the hand of the Chief Minister of the Province”.

The Section further elaborates thatsuch warrant shall not be issued unless the sum has, by statute of the Provincial Council been granted for services for the financial year during which the withdrawal is to take place, or is “otherwise lawfully charged on the Provincial Fund”, and that “the custody of the Provincial Fund of a Province, the payment of moneys into such Fund, and all other matters connected with or ancillary to those matters shall be regulated by rules made by the Governor”.

As would be noted, the above provisions of the law that deal with the appropriations and withdrawals from the Provincial Funds are specific and unambiguous, thus ensuringtransparency, accountability and integrity of the financial activities of the Provincial Councils. In that regard, it would be particularly noted that the specific provision relating to “withdrawals” from the Provincial Fund states that withdrawals can only be “under a warrant under the hand of the Chief Minister of the Province”. Accordingly, the law does not permit Provincial Funds to be withdrawn in any other manner, and consequently the funds of a Provincial Council cannot and must not be drawn out under the hand of the Governor or Chief Secretary or any other officer of the Province. Hence, it follows that, if any other person ever does so, such an act would be illegal and would amount to a clear misappropriation of “public property”, for which offence, severe sanctions are prescribed by law.

As is now known, by the end September 2017, the Sabaragamuwa Provincial Council stood dissolved as its term was completed, while in early October 2017, the North-Central Provincial Council and the Eastern Provincial Council also completed their terms. In the meantime, as a result of the hurriedly-passed Provincial Councils Amendment Bill on 20September 2017, a great deal of uncertainty has arisen as to when the elections to these Provincial Councils would be held, and the new Councils would be activated. The so-called “independent” Elections Commission too, has admitted that the Commission is unable to indicate a date for such elections with any degree of certainty.

In that background, the fund-raising and fund-disbursing activities of the above-mentioned threeProvincial Councils have now been rendered defunct and ineffectiveuntil such timethe respective Chief Ministers properly and legally assume duties following duly held elections for the Provincial Councils. It therefore follows that, until then, no payments can be legally made by such Councils, including even the salaries and other contractual payments.

To make matters worse, as and when the other Provincial Councils (in the rest of the country)also complete their terms, those Councils too, would suffer the same fate and be rendered defunct, since those too would be without a legal basis for the disbursement of funds. Accordingly, it hardly needs be said that the Provincial Councils administrationstructure, which includes thousands of schools, hospitals, and agricultural support units across the country, employing hundreds of thousands of public servants, has now been paralysed by the unintended consequences of this hurried legislation.That new amendment has also created an impasse which will surely be a prescription for absolute chaos in the administrative structure of the entire country as well.

As would be seen from the table, the Provincial Councils disburse and account for over Rs. 220 billion in expenditure per annum. The accountability and over-sight systems in place for that massive expenditurehave been enacted by Parliament to ensure that the required“checks and balances” are in place legally and administratively, so as to ensure the integrity of the finances belonging to the people of Sri Lanka. In terms of such “checks and balances”,payments cannot be legally made by the Provincial Councils’ administrative staff in the absence of the required legal empowerment. Therefore,in the coming weeks, there seems to be little that can be done to avoid that impending disaster leading to a total breakdown of the Provincial management, since the public servants are very unlikely to be reckless to take the law unto theirown hands and make payments to keep afloat, the three currently-dysfunctionalProvincial Councils.

It must also be stressed that, since the Government has damaged and/or destroyed the well-thought out systems in the Provincesas a result of the passage of hurried legislation to meet the perverse objective of postponing democratic elections, all persons who have been instrumental in recklessly promoting and indulging in such corrupt and disruptive practices, must be held accountablefor their actions at some future date. It would surely be the responsibility of a future government to do so, in order to restore the Rule of Law in Sri Lanka, which has slipped badly from the rank of 48th in the world in 2014, to the rank of 68th in the world in 2017, according to the internationally reputedWorld Justice Project.

(The writer is former Governor, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, and former Member, Finance Commission.)