Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday, 10 July 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

There are serious issues in education confronting the country today. Our priority from a development perspective should be the preparedness of 360,000 or so youth who turn 18 every year. They should be prepared for living and working in the 21st century – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Dr. W. A. Wijewardena recently published an article on the technology campus of the Sri Jayewardenepura University. I looked forward to new information on the State technology education, but I was sorely disappointed. His column was essentially a pitch for the Acting Vice Chancellor of Sri  Jayewardenepura. Interestingly, there have been several such pitches recently for the university itself. On a positive note, it is good that a university tries to justify the public expenditure incurred on it, but in the absence of a counter assessment, these advertorials could be window dressing for a rotten system.

Jayewardenepura. Interestingly, there have been several such pitches recently for the university itself. On a positive note, it is good that a university tries to justify the public expenditure incurred on it, but in the absence of a counter assessment, these advertorials could be window dressing for a rotten system.

There are serious issues in education confronting the country today. Our priority from a development perspective should be the preparedness of 360,000 or so youth who turn 18 every year. They should be prepared for living and working in the 21st century. The rest is details, I would say, because it is well established that the economic or social impact of education almost exclusively rests on school education, according to an extensive review of the literature by Alison Wolf in her 2003 book ‘Does Education Matter?: Myths About Education and Economic Growth’. While a highly educated few may contribute to innovation in the economy or society, mass higher education has no impact. A World Bank (WB) study of the same subject has shown that private benefits to higher education are many times greater than public benefits (WB, 2015).

Yet, our education system is designed to define education as success at receiving three passes for a paper and pen test at the end of 13 years of education. Then we select 10% or less of a cohort of such students for a free-of-charge education at public universities, leaving other 90% off the radar of policy makers or the public. The Tertiary and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) sector admitted 35,599 students (CBSL, 2018). Yet, I would include those attending the TVET institutions within 90% who are ‘off the radar’ because the TVET sector which is a distant poor cousin to the university sector is barely visible.

University education captures a lion’s share of education funding and media attention. Apparently, a discussion on amending universities have resurfaced as it does periodically. Such a discussion is like trying to change the deck chairs while the tertiary education ship is sinking.

The University Grants Commission regulates 15 public universities and associated institutes. The Technical and Vocation Education oversees 500+ state institutes (not counting 700+ private institutes) enrolling 35,000+ students for short or long courses, graduated about 26,024 National vocational Qualification (NVQ) certificate holders. These institutions receive Government funding no matter their performance.

What we need is a new commission which is a caretaker for all school leavers seeking a tertiary education and or training, not gatekeepers or apologists for underperforming institutions. These reforms will not happen unless the government overrides the interests of the higher education lobby.

Overly influential higher education lobby

Education funding in this country is driven by three powerful lobbies, The GMOA, the University Community, and Inter University Federation of University Students, a political arm of the JVP and/or the Peratugami Party. They serve to keep spreading the myth that free-of-charge education to a select few youth is free education, and policy makers and the media swallow the myth wholesale.

Their solution for the other 90% of youth is more and more public spending for education. Yes, it’s true that our education funding is way below international standards. As UNESCO noted: The Education 2030 Framework for Action proposed two benchmarks as ‘crucial reference points’: allocate at least 4% to 6% of GDP to education, and/or allocate at least 15% to 20% of public expenditure to education. Globally, countries spend 4.7% of GDP on education and allocate 14.2% of public expenditure to education; 35 countries spend less than 4% of GDP and allocate less than 15% of public expenditure to education (GEM Report, UNESCO)

Higher education interest groups lobbied for increased in education funding. However, the benefits did not go school education or the TVET sector because education funding formula is unduly tilted towards higher education at the expense of school education or TVET. The result is that university teachers are well remunerated now, and schoolteachers remain some of the poorest paid public servants.

Over-funding of universities

Our universities indeed receive a lion’s share of education funding in relation to international practices in education funding. As far back as 2002, the World Bank (WB) noted that our funding is unduly tilted toward universities.

By international standards, average recurrent education expenditures per student in Sri Lanka are modest at primary and secondary education levels, but high at the tertiary education level. Average recurrent education expenditure per student as a share of national income per capita on primary and secondary education, at about 9% and 11% respectively, are among the lowest in South Asia and East Asia. In contrast, average tertiary education expenditure per student as a share of national income per capita, [set] at 100%, is slightly higher than India, and substantially above the level in East Asian countries such as South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines. The main reason for the high share of public recurrent spending on tertiary education is the large unit cost of government universities. Overall, the pattern of average recurrent expenditure across education levels suggests that, in contrast to high performing East Asian countries, the balance of public resources in Sri Lanka may be tilted unduly in favour of tertiary education, at the expense of primary and secondary schooling (WB, 2005, Sec 16).

The internal efficiency of primary schooling (grades 1-5) and junior secondary schooling (grades 6-9), measured in terms of flow rates, are high (WB, 2005, Section 18).

Public university education in Sri Lanka is expensive, with high unit operating costs in comparison to other developing countries. In addition, there are wide differences in unit costs among public universities, ranging from about 40,000-120,000 rupees per student per year (WB, 2005, Section 20).

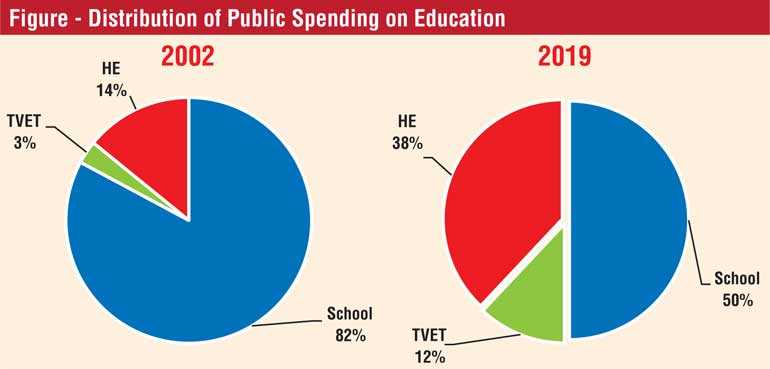

If education funding was titled in favour of university education in 2002, it is no better in 2019, according to our estimates.

The distribution of gross funding for education across the three sectors has widened since 2002. In 2002 Higher education received 14% of education funding. In 2019, this share increased to 38%. Funding for TVET sector too increased while the share for school education reduced to 50%.

It is true that new admissions to higher education have increased from 12,144 in 2002 to 31,451 in 2018, and new admissions to school education has slightly decreased from 328,632 in 2002 to 325,667 in 2018. We are still in the process of calculating the recurrent education expenditure per student as a share of national income per capita for 2018, in order to reassess funding situation vis-à-vis WB assessment published in 2005. However, a quick calculation of per student funding for universities v. schooling shows that per capita spending remains as tilted as reported by WB in 2005.

The problem lies in misplaced priorities. First, education achievement after 13 years of schooling is defined by the ability of a student to obtain passes for any three subjects in a national examination. As tuition teachers have revealed, a student can study for six months to obtain the necessary passes. Further, the government indirectly admitted that education is driven by private tuition by bending over backwards to change health regulation to suit private tuition needs.

Next, we increase funding for higher education to accommodate these students deemed suitable for higher education by a faulty indicator. In fact, we are trying to find solutions to a poor output at the end of the pipeline without investing adequately in the pipeline.

The evidence is strong that mass higher education does NOT contribute to development. Only research-driven higher universities have an impact. Hence, the priorities for government spending is clear. Quality school education, some further education or training for all youth, and research-based or inquiry-based higher education for a select few.

Unaccountable

University teachers who justify the expansion of public higher education point out that all higher education in developed countries are provided by the state. This is true indeed. In Canada or UK, almost all universities are publicly owned. In the US, private institutions co-exist but the federal government supports the education of all students, though loan schemes.

The comparison ends there because in Sri Lanka students are brought to the doorsteps of the universities. They come with public funds assured for their education, but there are no performance requirements for universities. Universities decide what courses to offer, how they teach, and they refuse to be held accountable for unemployability of graduates or the attitudes of these graduates. In US, USA, or Canada, public institutions receive funding based on enrolment and additional performance criteria. Retention and graduation rates of students are some such criteria. In Sri Lanka, a shockingly high percent of students dropout and the government does not to track that.

Further, in public higher education in other countries the students pay a share of the cost of education. For example, at Ohio State University where I worked as a strategic planning specialist, the budget consists of roughly about one third of cost recovered through student tuition fees, another one third though state subsidy, and the other one third through income generated through research funding, alumni giving etc. In UK and Canada too, students pay a share of the cost of higher education, giving a universities another good reason to be accountable.

UGC – a commission past its time?

The University Grants Commission was established in 1978 in the tradition of granting agencies in UK and India. The University Grants Commission of India continues to function but similar commissions in UK and eve USA have changed their roles.

In the nineties, the role of the Ohio Board of regent (OBR) was essentially the same as the UGC. Later, the OBR increasingly took on more responsibility for colleges and community colleges in the state, and today it is reborn as The Ohio Department of Higher Education with the mandate to “make college more affordable for Ohioans and drive the state’s economic advancement through the public universities and colleges of Ohio, the state’s network of public universities, regional campuses, community colleges, and adult workforce and adult education centres”.

UK has gone a step further:

The Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) distributed public money for teaching and research to universities and colleges. It closed on 1 April 2018. [It was] replaced by UK Research and Innovation [Agency] and the Office for Students.

This move in UK is very significant. It is an acknowledgement that research and innovation and mass higher education do not belong together, and that higher education agencies should serve the potential and current students, not the provider institutions.

Need a commission for students, not gate keepers for institutions

The UGC of has 15 institutions and 19 other associated institute. These institutions awarded 26,024 basic degrees in 2018. The Tertiary and vocational Education Commission (TVEC) is responsible for registration and accreditation of TVET institutions. TVEC reported 582 public institutions and 50,215 National Vocational Certificate awardees for 2019 from public institutions. We have 350,000 +school lavers who have left school at various points. Taken together these institutions cater to needs of about 20% of a youth cohort. What about education and training for others? The government may offer merit-based opportunities for some, but there should some accountability for others. What we have is a government that allows the higher education lobby to disrupt the education for the other 80%.

Present government is on the right track, more or less

As I pointed out, our universities receive an undue share of public funding thanks to a powerful higher education lobby. This situation must be corrected. Any additional funding for education should be directed to school education and 1-2-year colleges offering diplomas or advanced diplomas, while holding funding for universities at present levels. On the other hand, funding for research and innovation should be increased with centres of excellence within or outside of universities getting additional funding from the research and innovation budget.

In the present government, the higher education, technology and innovation portfolios are brought together. Bundling technology and innovation with higher education is unwise because higher education priorities are driven by a self-inflicted responsibility to find slots for students obtaining three passes from an outdated assessment system. New programs like the technology campus at Sri Jayewardenepura will not be able perform miracles to produce innovators. They will more likely than not produce more job seekers.

However, it is encouraging that the President has inquired about the feasibility of bringing all education functions under one ministry. This is good news. What we need is a ministry of education that oversees the education for all from early childhood to tertiary education, and a separate ministry of science, technology and innovation that funds centres of excellence in universities and elsewhere and nurture and award scholarships to select set of promising youth for a research-based or inquiry-based university education.

The writer is a scientist turned policy analyst specializing in governance and human capital issues. She can be reached at [email protected], [email protected] or [email protected]