Thursday Feb 12, 2026

Thursday Feb 12, 2026

Saturday, 20 April 2024 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

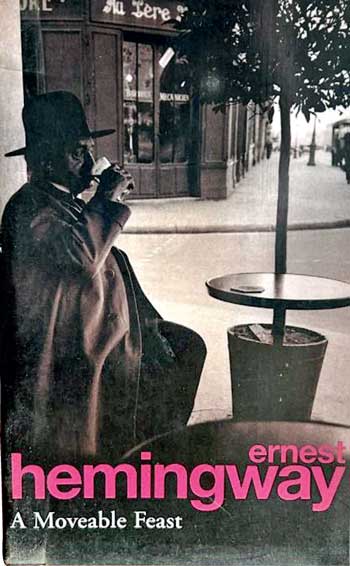

One of the most enchanting books I have read in recent times has to be “A Moveable Feast” by the celebrated American writer Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961). The book eludes easy categorisation, although it could be broadly considered a memoire of a period of his early life, when he lived in Paris (from 1921 to 1926). Hemingway had kept notes of his Paris days, getting down to writing A Movable Feast only in the last years of his life, in 1957 to be exact.

One of the most enchanting books I have read in recent times has to be “A Moveable Feast” by the celebrated American writer Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961). The book eludes easy categorisation, although it could be broadly considered a memoire of a period of his early life, when he lived in Paris (from 1921 to 1926). Hemingway had kept notes of his Paris days, getting down to writing A Movable Feast only in the last years of his life, in 1957 to be exact.

Hemingway did not live by halves, packing into his relatively short life every manner of adventure; travel, danger, women, booze, hunting, fishing; a life at full throttle. Travelling extensively, making short-term home in many countries every so often: France, Spain, Italy, China, Africa and even Batista’s Cuba. As a journalist covering the trouble spots of Europe through the tumultuous first half of the 20th Century; the two World Wars, Greco-Turkish War and the Spanish War, he was often in harm’s way. Hemingway suffered serious war wounds in Italy during the First World War, and fell dangerously sick while covering the Allied forces push towards Germany in the Second World War. As if this was not enough, he was in two near fatal air crashes in Africa and a horrific motor accident in the United Kingdom. Many of these experiences were later worked into his novels by Hemingway.

How “A Moveable Feast” came to be written

How “A Moveable Feast” came to be written

How “A Moveable Feast” came to be written is an interesting tale. Even after he had won the Nobel Prize (1954) Hemingway kept up his roving lifestyle, travel and adventure. In 1956, while on a visit to old Paris, he was reminded of the notes and manuscripts of his Paris days (1921-26) he had left in a trunk at the famous Ritz Hotel. In the distant 1920s the then little known American writer had been a frequent customer at the Ritz Bar. True to its classy reputation, the venerable hotel had kept the trunk safely (for 30 years!); Hemingway retrieved his notes most gratefully. The contents of that trunk led to A Moveable Feast.

The Ritz paid tribute to its celebrated customer, the hotel bar he frequented in the 1920s is now named after him, with a substantial collection of Hemingway paraphernalia; photos, manuscripts and even his old typewriter on display. Many literary minded visitors to Paris make the Hemingway Bar an itinerary item, sometimes one has to wait for a seat at the bar!

It may be a matter of interest to note that in 1979, the Ritz was bought by the Egyptian investor Mohamed Al Fayed. As well known, a few hours prior to her fateful encounter with the paparazzi on 30 August 1997, Princess Diana was at the Ritz hotel, as a guest of Dodi Fayed, the owner’s eldest son.

A Moveable Feast was published in 1964, three years after Hemingway’s death and 30 years after his Paris period. In the intervening years Hemingway had become a renowned writer, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954 for his celebrated book ‘The Old Man and the Sea” and other writings. The Nobel citation read “… for his mastery of the art of narration, most recently demonstrated in the ‘Old man and the Sea’, and for the influence that he had exerted on contemporary style…”

In 1921, he was only 22, just married, and he was in Paris.

Hemingway wrote – “If you are lucky enough to have lived in Paris as a young man, then whatever you go for the rest of your life, it stays with you, for Paris is a moveable feast.”

In Paris young Hemingway lived rather modestly, moving with his wife to a small apartment in the Latin quarter. There were many famous writers and artists who were living in Paris, several were in the nearby Montparnasse quarter; Pablo Picasso, Jules Pascin, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce and Scott Fitzgerald, to name a few. They would meet often in street cafes and bars, discuss their work, talk shop, eat and drink. The multi-coloured brightness of the Parisian life, the excitement and the vivacity of that vibrant city are conveyed obliquely in “A Moveable Feast”, Hemingway is a master at the art of unspoken implication.

Deterioration of our media standards

Hemingway supported himself by freelancing for American and Canadian newspapers, despatching articles and short stories regularly. We can assume that he earned enough in this manner to live in what is an expensive foreign country. Perhaps this is the secret behind the sturdy literary tradition and the bustling media these countries possess. They pay their writers well. Compare the situation in Sri Lanka. I know of a person who was a regular contributor to an English newspaper. He was financially strained and thought a periodic payment by the newspaper for his articles would alleviate his finances, while also acting as an incentive for his efforts. When he inquired from the Editor about this possibility of even a token payment, he was told rather abruptly that his reward would be the fact of publication in the newspaper. He does not write now.

The gradual deterioration of our media standards, as well as the paucity of literary efforts, tell a story. Institution building is not our strength; that such institutions are there only to benefit the owners is the crass attitude of the Sri Lankan media barons. From such scrooge-like souls no traditions can grow.

In his brief preface to the book Hemingway says: “For reasons sufficient to the writer, many places, people, observations and impressions have been left out of this book. Some were secrets, and some were known by everyone and everyone has written about them and will doubtlessly write more…”

“… if the reader prefers, this book may be regarded as fiction. But there is always the chance that such a book of fiction may throw some light on what has been written as fact.”

Without writing about the landmarks; the Eiffel Tower, Arc De Triomphe or the Pantheon (only a brief reference to the Louvre) Hemingway has given us an appetising offering of Paris and some of its residents of the time. Another, soon to be celebrated American writer then in Paris was Scott Fitzgerald (The Great Gatsby, Tender is the Night, The Beautiful and the Damned). They met, talked, drank, ate, travelled and even quarrelled.

In “a Moveable Feast” Hemingway described Scott Fitzgerald’s talent:

“His talent was as natural as the pattern that was made by the dust on a butterfly’s wings. At one time he understood it no more than the butterfly did and he did not know when it was brushed or marred. Later, he became conscious of his damaged wings and of their construction and he learned to think and could not fly anymore because the love of flight was gone and he could only remember when it had been effortless.”

Hemingway ends the book thus:

“There is never any ending to Paris and the memory of each person who has lived in it differs from that of any other. We always returned to it no matter who we were or how it was changed or with what difficulties, or ease, it could be reached. Paris was always worth it and you received return for whatever you brought to it. But this is how Paris was in the early days, when we were very poor, and very happy.”

“A Moveable Feast” received glowing accolades

“Vintage Hemingway … Written with that controlled lyricism of which he was master, these pages are marvellously evocative” – The Book Review

“Frank and moving…An invaluable portrait of the artist as a young man…when mere loving and mere writing were enough” – Book-of-the-Month Club

“Here is Hemingway at his best. No one has ever written about Paris in the 1920s as Hemingway” – New York Times

“An invitation to laugh with him amid the scenes of his youth where he was happier than he would ever be again…. a tragic grace…a heart-breaking quality” – Time