Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday, 14 June 2023 00:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

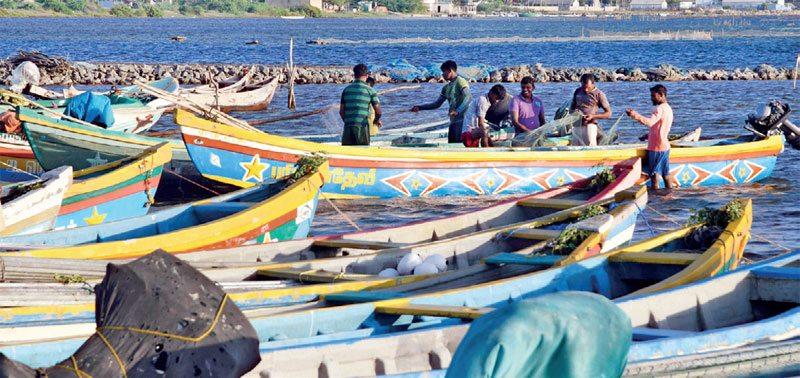

The North and East saw fewer protests amid Sri Lanka’s economic crisis, but disillusionment with mainstream parties is changing the region’s electoral politics – Photo: Bruno Press/IMAGO

President Maithripala Sirisena (centre) visits Jaffna in 2015, during the rule of the Yahapalanaya Government. In disappointing the North, that regime damaged hopes that even watered-down Tamil political aspirations could be realised in collaboration with Southern actors – Photo: Xinhua/IMAGO

By Amita Arudpragasam

By Amita Arudpragasam

www.himalmag.com: In 2022, in response to shortages, escalating inflation and a catastrophic economic crisis, a series of protests in Sri Lanka shifted the political fortunes of the Rajapaksa-led alliance, which had secured power with a parliamentary super-majority only two years earlier. The protests led to the resignations of Basil, Mahinda and Gotabaya Rajapaksa – respectively, the finance minister, prime minister and president. Sri Lankans publicly disavowed politicians accused of corruption and economic mismanagement, the Rajapaksas included, and protesters set fire to the homes of numerous politicians from the Rajapaksas’ Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP).

That May, there were reports that Mahinda was taking shelter at a naval base in Trincomalee, in the north-east of the country, along with his wife and children. The family is deeply unpopular in this region – where they oversaw the brutal conclusion of the Sri Lankan Civil War, fought most fiercely in the island’s North and East – but there were far fewer protests related to the economy here compared to elsewhere, and public outcry was less vocal.

When activists in the South asked why there was a lack of participation in anti-government protests in the North and East, the irony was clear. Tamils and Muslims, concentrated in the North and East, had voted as a bloc to prevent the presidency of Gotabaya Rajapaksa in 2019. They had low expectations of the Rajapaksa family to begin with. Protesters in these regions are also faced with intense surveillance, violence and state oppression in the aftermath of the war, such that the relatively peaceful progress of protests in the South, not immediately suppressed by brute force, was considered a privilege. Tamils noted a further hypocrisy: the Sinhala-dominated South rarely shows solidarity with protests held in the North and East against the Sri Lankan government’s failings and excesses.

Numerous other protests in the North and East have also had minimal impact, so there is cynicism about their utility. Families of the disappeared here, who number in the thousands, have been engaged in continuous protests since 2017, but have had no success in learning the fates of their loved ones. Although Tamils in Keppapulavu and Valikamam North have been calling for the return of their homes for years, many still live as refugees while their lands remain under military occupation. “There isn’t much hope that there will be a massive change here,” Dr. S. Sivathas, a consultant psychiatrist at the Jaffna Teaching Hospital, said. At the same time, there are some ways in which the North and East are acclimated to crisis. Sivathas added that older Tamils who have withstood hardship during and after the war have a higher level of psychological resilience.

While the South struggled to adapt to skyrocketing inflation and shortages of fuel and essential medicine, residents of the North and East were already accustomed to such inclemencies from their experiences of a war-time economy. Residents had to adapt to forced displacement, brain-drain, taxation by the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and an economic embargo imposed by the government that limited supplies of fuel, fertilisers, pesticides and other essentials. When Gotabaya, as the president in 2021, implemented a country-wide ban on agrochemicals in an ill-advised attempt to address the country’s foreign exchange shortage, some farmers were even able to revert to organic farming practices they had used in wartime.

While the South struggled to adapt to skyrocketing inflation and shortages of fuel and essential medicine, residents of the North and East were already accustomed to such inclemencies from their experiences of a war-time economy. Residents had to adapt to forced displacement, brain-drain, taxation by the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and an economic embargo imposed by the government that limited supplies of fuel, fertilisers, pesticides and other essentials. When Gotabaya, as the president in 2021, implemented a country-wide ban on agrochemicals in an ill-advised attempt to address the country’s foreign exchange shortage, some farmers were even able to revert to organic farming practices they had used in wartime.

The North and East are also perhaps better-equipped to withstand fuel shortages. As of 2016, 73% of households in the North and 58% of households in the East owned a bicycle, compared to a country-wide average of 30%. Even in urban centres in the North such as Jaffna, some homes have clay stoves and can use firewood to cook instead of gas or electricity. Shreen Abdul Saroor, a Mannar-based women’s activist, said that although small businesses were closed in the South during the worst of last year’s crisis, they continued to function in Mannar. “Because of the war, the north-east hasn’t been industrialised as much,” she explained. “And although townships really suffered, villages remained self-sufficient to some extent.”

On the edge

The North and East are not homogenous. Although a third of the population here is employed in agriculture – above the national average – not all farmers are self-sufficient. When food prices increased with the economic crisis, only some were able to lean on multi-crop home-gardens to sustain their families. Others, who practised monoculture, had several dependents or relied on electric pumps for irrigation (and were badly impacted by price hikes for electricity), generally fared poorly.

Many Tamils from oppressed castes, as well as Malaiyaha Tamils and returned Muslim communities, are also landless, leaving them especially vulnerable. Similarly, while traditional stilt fishers may have subsisted on their usual catch, those fishers reliant on kerosene to power their boats were unable to go out to sea. “Doctors, university lecturers, professionals, families that could depend on the diaspora … those were the communities that weren’t affected as badly,” Mahendran Thiruvarangan, a lecturer at the University of Jaffna, said. “But the majority of people have been impacted.”

This includes schoolchildren and working-class women. In January 2022, a World Food Programme survey found that 26% of households in the Northern Province and 35% in the Eastern Province faced food insecurity. “Some students don’t have enough food at home and so can’t concentrate in class,” one primary-school teacher observed when we spoke. “A parent told me that she couldn’t afford exercise books for her daughter and feels suicidal. When a parent feels this way, it impacts students.”

This includes schoolchildren and working-class women. In January 2022, a World Food Programme survey found that 26% of households in the Northern Province and 35% in the Eastern Province faced food insecurity. “Some students don’t have enough food at home and so can’t concentrate in class,” one primary-school teacher observed when we spoke. “A parent told me that she couldn’t afford exercise books for her daughter and feels suicidal. When a parent feels this way, it impacts students.”

Saroor said that domestic violence, child abuse, unsafe migration and unsafe labour have also increased through the crisis. She had recently returned from a free trade zone in Negombo, where the average wage is lower than Rs, 30,000 ($ 95). “Many workers there are from the north-east,” Saroor said. “Some women have joined the sex trade and want to know where to find condoms so they can have safe sex.”

Vulnerable communities often face multiple, intersecting crises. Angel Queentus, founder of the Jaffna Transgender Network, said that domestic violence can intensify when households experience financial duress. “We face harassment and violence when standing in queues,” she added. “Even receiving Samurdhi (welfare assistance) is challenging because we face issues with documentation.” According to Queentus, around half of Jaffna’s trans community has stopped purchasing hormones and some trans individuals have also delayed critical surgeries.

Dr. Sivathas, who is one of the few psychiatrists working in the North, said that communities in the north-east, despite their resilience, can be highly vulnerable when pushed to crisis point. They have few resources to rely on when it comes to mental-health assistance, and suicide rates in war-affected regions are much higher than elsewhere, he pointed out. “Young people are particularly vulnerable because they have lower levels of resilience than those who lived through the war.”

In the face of such precarity, the limited protests in the North and East still deserve close scrutiny. Mahendran Thiruvarangan said that “silence is constantly manufactured” and argued that there weren’t as many protests as in the South because “a powerful middle class civil society … drives the protest scene in the North.” Class privilege is tacitly compounded by the influence of the dominant Vellalar caste. According to Thiruvarangan, local civil society chooses which issues to rally around, and mobilises on political issues like disappearances or land-grabs by the military rather than economic struggles.

When groups did mobilise to protest during the economic crisis, some protesters held up placards asking for milk powder next to others holding placards asking for greater democracy, equality and the repeal of racialised counter-terrorism laws. Economic concerns were often presented in tandem with long-standing political demands, if at all. Sivathas noted that “political parties take up boiling issues in protests” but, because of existing disillusionment, “there aren’t many people interested in taking part in protests voluntarily.”

There is also little hope here that a change in political leaders alone can bring much by way of change. In April 2022, the Tamil Guardian reported that protesters marched past the office of the Eelam People’s Democratic Party, where its leader, Douglas Devananda, a minister in the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government, was reportedly watching. But this was an isolated event. An activist from Mannar observed that politicians affiliated to the Rajapaksas, like Devananda, were “in hiding” and temporarily “disappeared from the scene” during the height of the protests, but “they will not face a drop in popularity in the election.” This is a marked difference from the South, where politicians affiliated to the Rajapaksas or linked to corruption and economic mismanagement have seen enduring declines in popularity since the protests.

There is also little hope here that a change in political leaders alone can bring much by way of change. In April 2022, the Tamil Guardian reported that protesters marched past the office of the Eelam People’s Democratic Party, where its leader, Douglas Devananda, a minister in the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government, was reportedly watching. But this was an isolated event. An activist from Mannar observed that politicians affiliated to the Rajapaksas, like Devananda, were “in hiding” and temporarily “disappeared from the scene” during the height of the protests, but “they will not face a drop in popularity in the election.” This is a marked difference from the South, where politicians affiliated to the Rajapaksas or linked to corruption and economic mismanagement have seen enduring declines in popularity since the protests.

Another way

During the 2020 general elections, Angajan Ramanathan, a Rajapaksa ally from the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), claimed the highest number of preferential votes in Jaffna District. His popularity demonstrates how Rajapaksa-affiliated politicians have made electoral inroads into the North. Politicians like Ramanathan, Douglas Devananda, S. Viyalanderan, Sivanesathurai Santhirakanthan (also known as Pillaiyan) and Vinayagamoorthy Muralitharan (alias Karuna Amman), who rely on Sinhala Buddhist nationalists in government, are becoming an undeniable feature of north-eastern politics. They promise state patronage in the form of jobs, roads, schools, temples, community centres and more.

A decade ago, Ramanathan’s electoral victory would have been thought impossible. Tamils from war-affected areas believe the Rajapaksa brothers to be implicated in human-rights violations during the last stages of the war, and associate the family with Sinhala Buddhist ultra-nationalism. Any association with them and their politics was once politically ruinous here.

Traditionally, Tamils from the North and East have mostly voted for the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) – a grouping of Tamil nationalist parties, founded in 2001, that recognises the Tamils as a distinct people historically inhabiting the Northern and Eastern Provinces. The TNA advocates for the right to self-determination in these regions, and for the devolution of power from the central government to the provinces when it comes to health and education, natural resources and fiscal management. It belongs to a long tradition of north-eastern Tamil politics that prioritises nationalism, homeland and self-determination.

Undergirding this tripartite articulation of Tamil nationalism is a particular interpretation of economic history. In ‘The Economics of Tamil Nationalism’, the scholar V. Nithyanandam describes an “emerging reality” for the Tamils: that “economic viability could only be sustained with compatible political sovereignty.” This emergent reality is based on an assessment that large-scale investment and clear macroeconomic guidelines are required to stem human-capital outflows from the North and East. According to Nithyanandam, it emerged after multiple attacks on resources by successive post-independence governments.

Mainstreamed during the civil war, this emergent nationalism idealises austerity, self-sacrifice and any corporal or material hardship that facilitates Tamil political goals. This is exemplified by portrayals of Vellupillai Prabhakaran, the leader of the LTTE, who would reportedly tie himself up, get into a sack and lie under the sun for an entire day to improve his endurance. It was also demonstrated in the corporal sacrifices made by the Black Tigers, an LTTE suicide-attack unit, and in the LTTE’s justifications for its extractive tax systems.

Since this expression of nationalism considers economic progress for a Tamil nation unlikely outside of an autonomous political structure, it follows that the economic and material concerns of the Tamil people ought to be subsumed by or remain secondary to the Tamil political project. Today, several nationalist political parties still privilege the political rights and goals of Tamils over their material concerns. According to the economist Muttukrishna Sarvananthan, the form of ethnonationalism that emerged during the war also “took over the class politics of the Tamils,” leaving the economic needs of the working class unaddressed.

Although armed struggle left the North and East economically and politically devastated, the potency of Tamil nationalism in its dominant articulation restrained hand-out culture and patronage politics in the immediate post-war period. Patronage politics requires either large amounts of private financing or collaboration with a central government, and the latter is still considered antithetical to mainstream Tamil nationalism. Over time, however, collaboration with more moderate southern actors to defend Tamil rights or achieve a political solution to the national question has come to be considered increasingly politically tolerable.

The Yahapalanaya (“good governance”) regime in power from 2015 to 2019 was an experiment in this regard, and the TNA established a constructive relationship with key members of that governing coalition – which, notably, excluded the Rajapaksas and their party. The coalition collapsed without successfully resolving the Tamil national question or achieving much by way of protecting Tamil rights. This damaged hopes that even watered-down Tamil political aspirations – federalism within a unitary state, the repeal of draconian counter-terrorism legislation, the resettlement of displaced Tamils to their original lands – could be realised in collaboration with southern actors. It was in this context that patronage politics truly took off in the North.

Patron power

Gotabaya Rajapaska’s election as president in 2019 only heightened the political disillusionment. He is an especially provocative figure in the North, notorious for overseeing the brutal treatment of Tamils at the end of the war in his role as the defence secretary at the time. The continued rise of patronage politics, already noticeable in the 2018 local government elections here, was entrenched by 2020. “Many Tamils knew that Gotabaya Rajapaksa was not going to do anything politically” for them, Thiruvarangan said. “He was consolidating in a major way, militarising everything.” So Tamil voters “would have thought focusing on political issues now was a waste of time, let’s focus on economic concerns.” Younger voters especially – less concerned by the history of ethnic conflict and increasingly connected to the internet – sought to fulfil material aspirations instead.

Gotabaya Rajapaska’s election as president in 2019 only heightened the political disillusionment. He is an especially provocative figure in the North, notorious for overseeing the brutal treatment of Tamils at the end of the war in his role as the defence secretary at the time. The continued rise of patronage politics, already noticeable in the 2018 local government elections here, was entrenched by 2020. “Many Tamils knew that Gotabaya Rajapaksa was not going to do anything politically” for them, Thiruvarangan said. “He was consolidating in a major way, militarising everything.” So Tamil voters “would have thought focusing on political issues now was a waste of time, let’s focus on economic concerns.” Younger voters especially – less concerned by the history of ethnic conflict and increasingly connected to the internet – sought to fulfil material aspirations instead.

“I voted for Angajan Ramanathan,” said Sana, a trishaw driver in Vaddukoddai on the Jaffna Peninsula, a little embarrassed. His choice reflects diminishing confidence in the once dominant TNA, which lost almost 40% of its parliamentary presence in the 2020 general elections. The alliance’s ability to secure Tamil rights in collaboration with the South was called into question, and it only belatedly prioritised the economic concerns of its voters. Some of the TNA’s lost votes accrued to other Tamil nationalist groups like the Tamil Congress and the Tamil People’s National Alliance, but non-Tamil nationalist parties like Ramanathan’s SLFP increased their share of the vote in the region too.

In his campaign, Ramanathan highlighted his proximity to the Rajapaksa family to demonstrate his ability to secure patronage. As state resources have run dry with the economic crisis, Ramanathan faces a challenge to deliver on campaign promises based on official largesse – a problem compounded by his status as a relative political newcomer. Other politicians like Devananda, who entered politics in the 1990s, are less likely to be impacted by the economic crisis as they have had long-term access to state patronage and have built up loyal voter bases over time.

Given the economic underpinnings of Tamil nationalism, the emergence of a new type of Tamil political representative – one able or at least willing to elevate economic needs over political aspirations – is significant. Such politicians subvert the logic that political autonomy must precede economic development. Campaign rhetoric around “development” currently centres on short-term material gains rather than substantive visions for central-government economic policy. But this is nevertheless an important departure from the political goals that characterised a previous era.

Patronage politics and the predominant articulation of Tamil nationalism also help explain why there were fewer protests related to the economic crisis in the North and East. Voters seeking patronage are more likely to simply move to other parties or actors promising patronage rather than join protests in the hope of a major political change. In the South, political patronage comes from the major current political powers – the Samagi Jana Balawegaya, the SLPP and the SLFP – wherever they may stand on the economic or political spectrum. A significant number of swing voters move towards the party or coalition likely to win elections in anticipation of securing patronage. In the North, however, most state patronage comes through the SLFP and SLPP, or Tamil parties allied to these parties. Many Tamil nationalists still see alliances with the government now in power as a betrayal of the Tamil political project, and the refusal of parties like the Tamil National People’s Front to collaborate with State actors means they have less access to state patronage. The lack of options for voters seeking patronage will be limiting, but may create space for new independent candidates.

Elankovan Chandrahasan, an aspiring provincial council member, said that there isn’t enough debate around economic policy in the North and East, but the discussions that do occur usually revolve around self-sufficiency or economic sovereignty. Except perhaps for limited gains in tourism and primary production, grandiose promises by the state for post-war economic development never came true. “People see that the state has continued to block trade by keeping the Talaimannar–Rameshwaram ferry closed, by not developing the Kankesanthurai port, the Trincomalee harbour and the Palaly Airport,” Chandrahasan added.

In other words, patronage politics aside, the large-scale investment and macroeconomic vision that Nithyanandam posits as necessary for true economic progress has not arrived. This lends credence to the Tamil nationalist assumption that economic progress hinges on political sovereignty, and that, given anti-Tamil racism, the state will never deliver for Tamils. “People believe that the state has blocked these developments,” Chandrahasan said, “and on ethno-religious grounds is trying to stifle the economy” in the North and East.

Although the disillusionment with traditional politics and the trend towards patronage politics is clear, it is still difficult to know if and how mainstream Tamil nationalism will evolve to accommodate the economic aspirations of the region. As the debates continue, voting patterns too are hard to predict. Sana, the trishaw driver, explained that while Ramanathan did have the road outside his home paved, he may not vote for him again. “What’s the point of a road, when there’s no fuel?” he asked.

(The writer is a researcher and independent policy analyst from Sri Lanka.)

(This article was produced with support from Internews.)

(Source: https://www.himalmag.com/patronage-politics-economic-crisis-sri-lanka-north-and-east/)