Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday, 5 March 2020 02:07 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

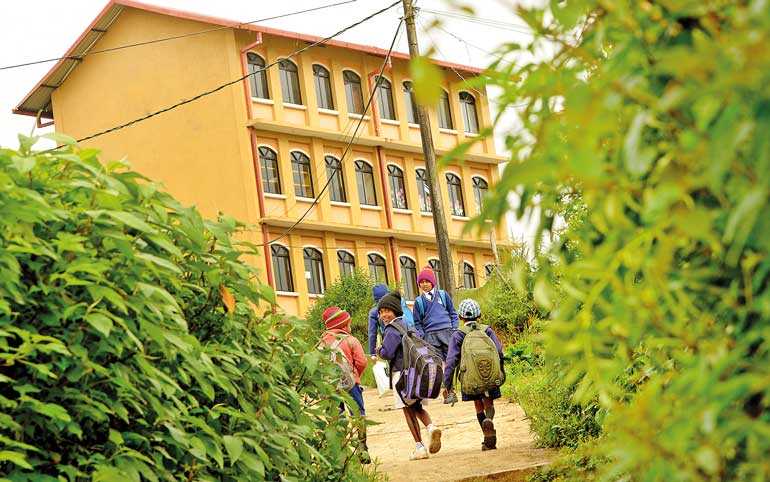

The only expectation that a child has is to be loved by both his or her parents and teachers, but the mental anguish and physical torture that children have to endure at home and in an educational institution that is supposed to be the epitome of love and compassion no doubt has left many children with scars that they will take to adulthood – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

A 13-year-old female student from Gampaha District desperately appealed to ban the sale of canes in Sri Lanka because every class in her school has a cane, which is put to maximum use at every lesson of every day.

She watched helplessly as a nine-year-old boy wet himself in front of the whole school while the teacher-in-charge of discipline took a moment to choose from six different canes from her office. That is approximately six hours per day equivalent to 14,400 hours of exposure to violence in a child’s life at this particular school.

Child abuse seems to be on the ascendency over measures taken as discipline by parents and teachers. There is alarming evidence that parent and teacher frustrations and their own psychological sicknesses are inflicted on helpless children who do not know what their rights are.

The only expectation that a child has is to be loved by both his or her parents and teachers, but the mental anguish and physical torture that children have to endure at home and in an educational institution that is supposed to be the epitome of love and compassion no doubt has left many children with scars that they will take to adulthood.

The competitive world we have created for ourselves has impacted on parents who suffer considerable stress when it comes to bringing up children. This stress extends to teachers, most of whom are parents themselves on the one hand and also called upon to manage children in difficult circumstances such as large class rooms and interference by politicians and law enforcement authorities.

As we know and are used to hearing it, children are children, and in their formative years, they are trying to find themselves without a particular plan or knowledge of any particular direction they should be going. They are children and they are not expected to have any such plans. This where love and nurture comes in, to make their childhood as happy as possible, whether at home or in school and not to corral them in physical or mental cages, but to guide them with loving kindness to become caring and responsible citizens in their adulthood.

The stress and hardships that parents and teachers endure needs to be understood. However, the answer cannot be in abusing children as a means of releasing their own psychological suffering. There is a stark difference that distinguishes the two situations. Parents and teachers had/have choices, children don’t. Parents brought the children to this world and teachers chose their vocation.

The rising trend of physical abuse of children in Sri Lanka

A study on ‘Child Disciplinary Methods Practiced in Schools in Sri Lanka’ conducted by National Child Protection Authority (NCPA) in 2017 revealed that 80.4% of students reported having experienced at least one episode of corporal punishment, 53.2% of students experienced at least one episode of physical abuse and 72.5% of students experienced at least one episode of psychological aggression in the past term.

This is further endorsed by the alarming rise of complaints received by NCPA. In 2010 NCPA received a total of 3,892 cases and 905 were of cruelty to children. In 2018 NCPA received a total of 7,342 cases and 2,413 were of cruelty to children. Physical punishment remains the single most common form of abuse of children globally.

Since the dawn of 2020, there have been daily reports of abuse of children, some more gruesome and inhumane than the previous. We are gradually hypnotised to desensitise and dismiss these as another ordinary incident.

There is a considerable degree of researched evidence that children spanked frequently and/or severely are at higher risk for mental health problems, ranging from anxiety and depression to alcohol and drug abuse in later life. There is also evidence of an increased incidence of aggression among children who are regularly spanked. Many parents spank their children to put an immediate stop to bad behaviour (e.g., shoving another child, reaching for a hot stove, etc.).

Being on the receiving end, children may learn to associate violence with power or getting one’s own way. Indeed, much of the aggressive behaviour attributed to children who were spanked differentially tends to correspond to interactions where violence is used to exert power over another person—bullying, partner abuse, and so on.

The falling trend of child rights

Sri Lanka ratified the United Nations Convention of Rights of the Child (UNCRC) in 1992. In the concluding observations of the UNCRC on the combined fifth and sixth periodic reports of Sri Lanka in January 2018, serious concerns were raised and in respect of which urgent measures must be taken: violence, including corporal punishment (para. 21), sexual exploitation and abuse (para.23), economic exploitation, including child labour (para. 41), administration of juvenile justice (para. 45), and reconciliation, truth and justice (para. 47).

Although the National Action Plan for Protection and Promotion of Human Rights 2011-2016 had big plans to eliminate Corporal Punishment in schools, actual action on the relevant issues have not materialised. In contrast, there is no mention of Corporal Punishment in the National Action Plan for the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights 2017-2021.

Former President Maithripala Sirisena and current Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa both endorsed child protection on the campaign platforms but after gaining office, appear to have consigned this to being of less importance than protecting teachers who use punishment as a form of discipline.

The vanishing trust in law and justice

The failures of the Police, Judiciary and Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) in protecting our children and promoting their rights have resulted in frustrating inadequacies and lengthy and painful progression of inquiries.

By the end of 2017, there were over 17,000 cases of child abuse stalled at Attorney General’s Department dating back as long as ten years. This figure is believed to have risen over 20,000 by end of 2018. The victims have lived a life of hell tormented by the horrendous memories without any hope of justice.

One family experienced unimaginable institutionalised corruption whilst exhausting every avenue to seek justice against corporal punishment and mental abuse of a child in the hands of educators. Their case was thrown aside by all the Courts up to the highest level in Sri Lanka and it has now been submitted for consideration under the first Optional Protocol to the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) at United Nations Human Rights Commission (UNHRC).

If this complaint is successfully upheld as an infringement of children rights and its abuse through corporal punishment, there is real hope for five million or more children of Sri Lanka and millions elsewhere.

This case and the many that are pending in the Attorney General’s Department have shown that children effectively have very little or no rights in Sri Lanka despite lip service paid to it in public. Misinformed and misguided parents as well as teachers have in the main curtailed these rights, knowingly or unknowingly, and authorities who are expected to uphold these rights have reneged on their responsibilities leaving children in deeply distressing and vulnerable situations.

All political leaders and governments to this day have not taken any firm steps to address some of the reasons for parent and teacher behaviour, and children have been, and continue to be, the meat in the sandwich as a consequence of this inaction.

One can only hope that President Gotabaya Rajapaksa might be the leader with a difference who will take tangible and effective steps to unconditionally recognise and safeguard children’s rights while at the same time look into the genuine grievances of a majority of teachers who are basically very loving and kind to children.

The behaviour of a few teachers who are fundamentally psychopaths should not be allowed to define the nobility of the teaching profession and tar the good name of an overwhelming number of teachers. Such teachers should be removed from any further sullying and dirtying the teaching profession by abusing vulnerable children.