Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 4 June 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

First things first: if the story is true, and 118 Parliamentarians have received Perpetual boodle, the bond entrepreneur should not be in prison. With that much clear command in the House, he should be in Temple Trees.

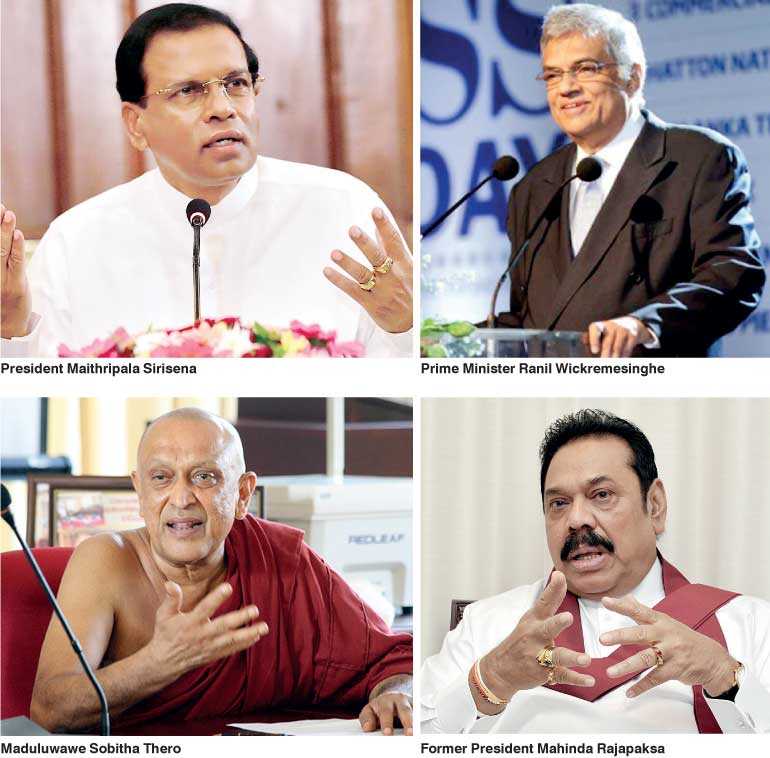

President Maithripala Sirisena is unlikely to command a chapter or earn a paragraph in our post-colonial history. He will, of course, be a footnote in the convoluted chapter on our struggle to return to a Parliamentary democracy, if or when we succeed in ditching the travesty of the Executive Presidency.

The man was doomed from the start. His character and character flaws are straight from the Russian classics. Fyodor Dostoevsky has described his kind: “But man is a fickle and disreputable creature and perhaps, like a chess-player, is interested in the process of attaining his goal rather than the goal itself.”

His presidency of the last three years is a bad Russian novel. Today, he is the character out of Pushkin: “It’s a lucky man, a very lucky man, who is committed to what he believes, who has stifled intellectual detachment and can relax in the luxury of his emotions - like a tipsy traveller resting for the night at a wayside inn.”

The President’s reference to burglarising of the ‘Big Bank – Maha Bankuwa’ did not create any waves. Instead, his remark about helicopters was noted, picked up, and soon snowballed in to an unusual uproar and an exceptional extravaganza of political rhetoric. That says a lot about our mass media, social media, and our opinion makers.

The President’s remarks did have an impact on two professional journalist friends of this writer. One said that the President was unhinged. The other described it as an outburst. This writer does not intend to quarrel with either of them. They are what constitutes the urban liberal middle class of our land.

Having listened to the 42-minute speech in full, the considered opinion of this writer is that President Sirisena has now reached the identical point that Alice reached in her wanderings in Wonderland, when she met the Cheshire Cat.

The Cat asks Alice: “Where are you going?”

Alice responds: “Which way should I go?”

The Cat says: “That depends on where you are going.”

Alice says: “I don’t know.”

Then The Cat tells Alice: “Then it doesn’t matter which way you go.”

Our Prime Minister knows his fairy tales. He excels in spinning them well. The Prime Minister has decided to remain on high ground. He has parried the issue, not very deftly, but with some degree of resolve: “It was essential to focus on country’s development at this moment instead of talking about other issues.”

He has also directed the State Film Corporation to ensure that cinema hall owners provide 3D spectacles to cinema goers. That is how it should be. Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe excels in the art of political bioscope. Now he has decided to go three-dimensional.

Our politicians, from both sides of the barricade, are in a silent conspiracy to maintain their hold on the minds of the populace.

There was an encounter at Temple Trees in the early hours of 9th January 2015. It was between then-President Mahinda Rajapakse, who was losing his bid for a third term, and then-Leader of the Opposition Ranil Wickeremesinghe, hopelessly hoping to access state power as soon as it was possible.

The outgoing President and the incoming Prime Minister shared a broad ‘world view’. Maduluwawe Sobitha Thero was a ‘nuisance’ but something they both could handle. Sobitha Thero’s Common Candidate was only a small part of that ‘nuisance’ equation. It required reciprocal management. The last three years is proof of their foresight and sagacious strategy formulation.

Both knew in those early hours of 9th January 2015 that despite the hype that would follow, it was not a new dawn but very ordinary dawn. They both relied on the apathy of the people and their demonstrated perception of helplessness in confronting power.

One relied on the people’s penchant for ancestral worship and the ‘Kurahan’ collared shawl. The other relied on his ancestral privilege and the loyalty of the UNP working committee. The two seasoned players knew quite well that it was only a matter of time. The minds of the populace will quietly and comfortably slip back in to the familiar sense of reasoned indifference.

They knew that ‘We the People’ would soon get over the ‘Sobhitha syndrome’ and settle down to conduct business as usual. “That’s the way things happen, and we can do nothing about it.”

Ranil Wickremesinghe did not vote against the 18th Amendment that removed Presidential Term limits. He walked out. Mahinda Rajapakse did not sign the No-Confidence Motion against Ranil Wickremesinghe. He has observed a conspicuous neutrality on the Bond business. His expressed views on the issue of Bonds have remained strictly for purposes of optics.

Mahinda is not an autocrat per se. He only made concessions to his brother Gotabhaya’s megalomania. As time elapsed, he found that autocracy was more convenient than exercising his charming charisma.

Ranil Wickremesinghe is different from Mahinda Rajapakse. Quintessentially, he is the ‘inverted autocrat’. He is a true believer in the power of concentrated wealth. He cannot help it. He was born to that role. No sooner he assumed office, real power moved in to the hands of an amorphous organism that he created. It is a shapeless, formless mechanism consisting of self-pronounced experts on economics, job generation and you name it, they know it!

This writer has known one of them – the octogenarian of the team – at close quarters. His theory is simple. Kick the can down the road long enough for people to get used to the noise. The problem is solved. Others take over and the can gets kicked further and further down the road. Nobody notices. Sometimes, somebody will even complain that they no longer hear the noise of the tossed can! Now that is real development economics for you.

Much has been made out of the so-called Bond scam. There is no scam if the scam was not probed. The ‘Gamarala’ did the unthinkable by appointing a commission. But then some common sense prevailed in the ranks of the privileged class. The Prime Minister first submitted an affidavit. He later clarified the clarifications in his affidavit.

Martin Wolf, Deputy Editor and Chief Economic Commentator of the Financial Times, wrote thus in 2014, hardly a year before our problem: “A system that is based … on the ability of profit-making institutions to create money as a by-product of often grotesquely irresponsible lending is irretrievably unstable … ordinary tax payers are being forced to suffer in order to save a banking system that has brought them only excess and ruin. This is intolerable: indeed, a form of debt slavery …”

Ranil knew the system of debt slavery. Ranil knew who should replace Nivard Cabraal. We should not blame the Prime Minister. His expertise is on the working of the system. How was he to know what the submissive, unassuming ‘Gamarala’ president would do? Who expected a commission of inquiry?

The phenomenon and the predicament of the Common Candidate must be examined in this context.

Sobitha Thero’s believability was the pivot of the common candidacy. It succeeded briefly in overpowering the apathy of the people. Sobitha Thero did not advise anyone to burglarise banks. Neither did he advise the Common Candidate President to make his brother the boss of Sri Lanka Telecom. Sobitha Thero would not have approved of A S P Liyanage representing us even in Burkina Faso - wherever that land may be - let alone in the rich emirate of Qatar. Sobitha Thero did not advise the Common Candidate to compete with Mahinda Rajapakse for the Sinhala Buddhist tribal totem.

People who claim to stand for something must stay standing. When they only brag about what they stand for, they are squatting on what they should be advocating. We are irritated by rascals. We are intolerant of fools. We are prepared to love the rest. Where do we find them? Where are the people who deserve our love?