Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Monday, 12 February 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By the time this column is published I am sure the final verdict of the Sri Lankan voters will be loud and clear. Freshly elected members to the local government institutions, hopefully with 25% female representation, must be gearing to “serve” the deserving community. The fundamental question still remains as to how to assess the effectiveness of public sector performance.

Moving beyond mere rhetoric, the reality is the absence of a robust performance management mechanism in the public sector. Today’s column is an attempt to shed light on this vital aspect towards national prosperity.

Overview

Performance management as a concept is not uncommon to the Sri Lankan public service. How it is currently done is the question. In Sri Lanka, the measurement of an individual employee’s performance had been introduced through a public administration initiative way back in 1998. The objective was to link the granting of annual increments of public officers to a proper appraisal of work performed during the period considered for increment. The Government has adopted this as a policy ever since.

The Sri Lanka Administrative Service (SLAS) Minute was amended in 2005, accommodating special provisions including opportunities to fast-track promotions for SLAS officers. The provisions enabled SLAS officers to sit for a promotion examination on the condition that they maintain “above average performance” consecutively for five years. This was an unprecedented major breakthrough which was recognised in policy by a specific salary circular.

Despite the fast track, the method of conducting evaluations remained the same. However, the performance evaluation system did not get amended nor did the measurement system. Thus, the new policy demand and the old appraisal system became an obvious misfit resulting in many deadlocks

Management for development results

Amidst the growing dissatisfaction toward the existing performance evaluation, the need for an overall conceptual framework to relate the individual performance was also identified. Management for Development Results (MfDR) tested and proven in many public circles around the globe was seen as a suitable approach.

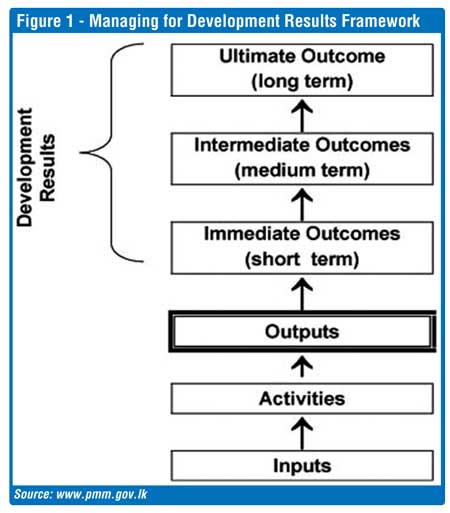

Figure 1 contains the basic details of MfDR framework. It moves from short term to long term and also from activities, outputs and outcomes.

MfDR focuses on development performance and on sustainable improvements at the country level. It also includes practical tools for strategic planning, risk management, progress monitoring and outcome evaluation.

In essence the perspective of impact or result is the central focus. In simple terms, for a desired result to be generated there should be an outcome. For the desired outcome there should be outputs. For desired outputs to appear there should be a series of activities that need to be done.

Linking development to performance

Ministries and departments are supposed to develop a vision, mission, strategies, goals and action plans. Departments in particular have a mandate established by acts in Parliament. Accordingly, their respective reasons for being present are well articulated. In essence, the outcomes that they want to produce and the impacts are self-evident in their vision and mission statements.

Under the prescriptions of the General Treasury, each government institution submits its corporate plans each year. Accordingly, their outputs towards achieving the outcomes are made clear.

The rationale for such a line of thinking to link MfDR with Individual Performance is that the impacts that departments desire to create should pass down from the institutional level to the interactive team level and then to the individual level, which in turn produce results from the individual level to spill over to the interactive team level and institutional level respectively. It in fact links individual, division, department, ministerial and policy levels sequentially.

The flow from the individual performance leads to Divisional Management Plans and to Strategic Departmental Plans which can be linked to results-based budgets as well. In essence the broader policy objectives will be achieved if the individual level performance is correctly agreed to by the individuals and performed within a stipulated time.

KRAs, KPIs and KBIs

The new performance evaluation should focus on two key aspects, tasks and competencies. Tasks involve Key Result Areas (KRAs) and associated Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Competencies involve Key Behavioral Indicators (KBIs). The intention here is not to go into details but to highlight the novelty and necessity of the approach.

Identification of KPIs will rely on the key results that an institution is deemed by the very establishment of the particular institution. In other words, its mandate articulated in respective acts or other legislative enactments. Once the key result areas are agreed on at the strategic level, the key divisional objectives will be made clear and those will be mentioned in the first page of the performance plan as a measure to keep the rest of the document in check.

Key Performance Areas will be derived from the divisional objectives spelt out in each performance plan. Derivation of tasks, which can range from one to many, will then depend on the key performance areas that have already been identified.

KBIs on the other hand refer to the broad aspect of competencies. According to Gary Hamel and C.K. Prahlad, “core competencies are the collective learning in the organisation, especially how to coordinate diverse production skills and integrate multiple streams of technologies.”

In the public sector the demanded set of skills may vary from being generic to specific: on the whole an individual might need to master a set of skills that are generic but when it is referred to a position like a Divisional Secretary, soft skills like public relations would be pivotal.

Just like the need to master the skills, the need to check on the employees building their competencies and how they showcase their required skills in their respective performance can only be measured by putting what the key behavioral indicators are up on the board.

The cascading effect from results to outcome, outcome to output, output to input and vice versa should be clearly identifiable in the performance appraisal system. Institutions need to rediscover their respective identities through re-reading their own establishments. Each institution needs to establish effective monitoring systems either Information Technology-based or manual in order to make certain that objective measurement becomes likely and feasible.

A successful case from Australian public sector

I have met many a cynical public administrator who was pessimistic about a performance management system. Their major concern is subjectivity and favoritism with possible political interference.

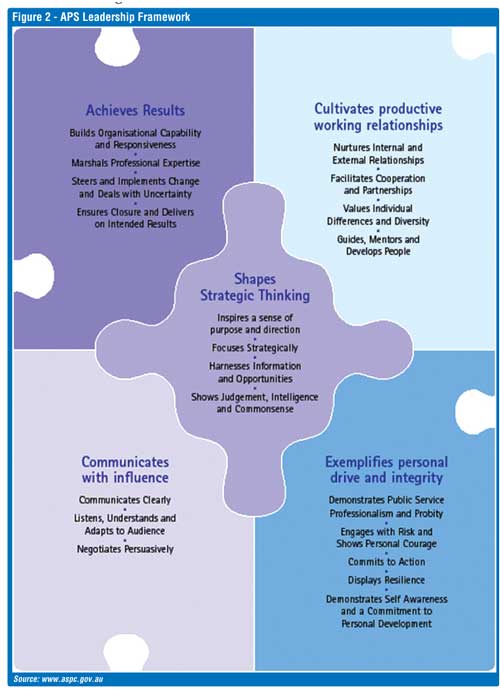

I came across an interesting case in the Australian public sector as to how they are managing, monitoring and measuring public sector performance. The starting point is a solid and lucid framework. Figure 2 contains the details.

It is interesting to note that the framework was developed as a consequence of the Australian Government introducing a public sector reform agenda in 1998. The reform agenda recognised the importance of leadership capability as a key foundation of the new vision of a high-performing public service. The intention here is not getting into details but to show the preciseness and the practicality of approaching the public sector performance.

Senior executive leaders in the Australian Public Service (APS) play a key role in the delivery of the core functions of the service. They provide high-quality policy advice to Government and implement Government programs, including delivering services to the community. They have a particular accountability to ensure the delivery of outputs that contribute to the achievement of outcomes as determined by the Government. They must be able to focus on the outputs specific to their agency and the links between these outputs and broader government goals. This requires them to create a shared vision and sense of purpose for their organisations, to enable and motivate their staff to achieve high performance.

The Senior Executive Leadership Capability Framework seeks to establish a shared understanding of the critical success factors for performance in APS leadership roles. The framework identifies the five core criteria for high performance by senior executives. Each of the criteria heads a group of inter-related capabilities. The framework does not describe the functions or responsibilities of particular senior executive roles.

The capabilities are based on the requirements of the APS now and into the future. They have been identified through extensive, validated research and consultation with a wide range of leaders in the APS. The balance between and within the five criteria is dependent on the work of the particular agency, the demands and levels of individual jobs and the mix of skills required in the senior executive team.

Moving ahead

I do not want to paint a gloomy picture. There are glimpses of achievements and loads of positives about the public sector administrators. I have met many such leaders in the Master of Public Administration (MPA) program of the Postgraduate Institute of Management (PIM).

The way the public sector promptly acted with commitment and care during the tsunami is one classic example. The much improved efficiency we see in the Department of Immigration and Emigration is one recent example. The same can be said of many E-government initiatives such as the E-Pensions Scheme and E-Revenue License. The fundamental challenge is to share best practices within the public sector so that they can essentially become the next practices of lethargic institutions. It essentially boils down to leadership at all levels.

(Prof. Ajantha Dharmasiri can be reached through [email protected], [email protected] or www.ajanthadharmasiri.info.)