Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday, 13 March 2024 00:24 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The stabilisation of the economy and the adoption of International Monetary Fund (IMF) program requirements has created optimism that Sri Lanka is heading in a positive direction. While the direction is positive, where this is going to lead us is not.

The stabilisation of the economy and the adoption of International Monetary Fund (IMF) program requirements has created optimism that Sri Lanka is heading in a positive direction. While the direction is positive, where this is going to lead us is not.

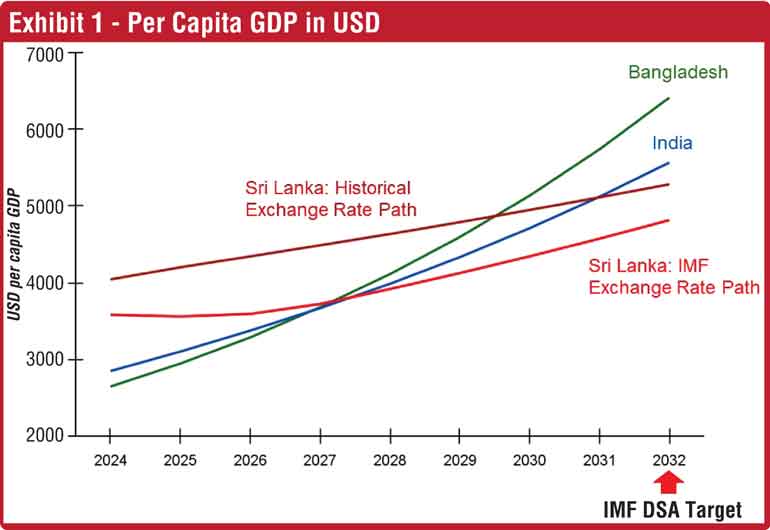

If Sri Lanka follows the IMF program to the letter, it is poised to have a smaller per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) than India and Bangladesh by 2032. The measure of a country’s economic strength is the income per person, or GDP per capita, as more populous countries naturally have larger total GDP. At present, Sri Lanka has a higher per capita USD GDP than both India and Bangladesh, but both Bangladesh and India are projected to grow much faster than Sri Lanka according to the IMF (see Exhibit 1). Residents of Vietnam and the Philippines will be earning 35% and 25%, respectively, than the average Sri Lankan by 2028. Such differences are extremely difficult to catch up to. For example, Sri Lanka is so far behind Singapore that to catch up in 2053, Sri Lanka will need its current per capita GDP to be almost 80 times higher – something so outside of current projections and policies that Sri Lankans will never earn as much as Singaporeans.

The data underlying my analysis comes from the IMF and the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. For Bangladesh and India it is from IMF World Economic Outlook 2023, and for Sri Lanka from First Review of Sri Lanka’s Extended Fund Facility, EFF, Arrangement in December 2023. The path of the Sri Lankan rupee USD exchange rate projected by the IMF is obtained from the IMF EFF Review by comparing the US Dollar and Rupee GDP figures. Population figures are also from the IMF World Economic Outlook until the end of 2022. Using the IMF’s GDP figures and dividing by the IMF’s projected population growth rates, I find Sri Lanka’s per capita GDP in USD till 2028. From 2028 onwards, we assume all variables will continue to grow at the same rate as projected for 2028 by the IMF.

To discipline the analysis, I consider two alternative paths for the rupee exchange rate. If the IMF’s exchange rate projections are used, Sri Lanka will fall behind India and Bangladesh’s per capita USD GDP by 2028. When I consider a depreciation rate of 4% per year, which is based on the average depreciation rate of the rupee over the 20 years preceding the crisis, Sri Lanka can still expect to be behind India and Bangladesh by 2032, the year in which the IMF debt sustainability targets should be reached.

Consistent and bold Government policies help the rapid growth of India and Bangladesh. Bangladesh’s US dollar per capita GDP is set to grow at over 9.5% per year over the next five years by bolstering its financial sector by addressing vulnerabilities and enhancing banking regulation, supervision, and governance.

The country also aims to deepen capital markets to secure financing for growth objectives. Moreover, it plans to prioritise trade liberalisation and improve the investment climate to boost trade, diversify exports, and attract foreign direct investment. Additionally, efforts to enhance productivity through education, skill development, and increased female economic participation are crucial for unlocking greater growth potential.

Through several key structural developments, India is expected to grow at 8.8% per year. These include accelerating capital spending in the near term alongside a neutral monetary policy stance anchored on data dependency. Bilateral trade agreements are underway to liberalise the FDI regime and improve the investment climate. Furthermore, ongoing efforts to enhance public infrastructure investment, ease information asymmetries, and improve the business climate are anticipated to stimulate private sector investment.

The recent experience of Greece has shown us that striving for economic stability alone is not sufficient. As I have been warning since the early days of the crisis, Sri Lanka is on the same path as Greece: Greek per capita GDP in 2007 was 12th out of 19 Eurozone countries, by 2024 it was 18th, and is still 30% less than it was before the crisis there 17 years ago. Unfortunately, as in Greece, austerity, Government capture by interest groups, poor governance, and lack of political will to enact bold reforms have been evident since the start of the crisis in Sri Lanka.

In collaboration with Verite Research, I have repeatedly advocated for broad-based inclusive policies that spread the burden of the crisis. Such policies, together with carefully evaluated development spending, will maximise the possibility of robust and sustainable growth and political stability. The reality has been the opposite. For example, additional tax revenue, the need for which could have been avoided by a broad-based and fair restructuring of domestic debt (DDR, or as the government coined it, DDO), is then raised by increasing VAT and increasing electricity tariffs, among other things: items that bite into the budgets of the marginalised and the rapidly disappearing middle classes. While these actions helped satisfy the accounting requirements of the IMF debt sustainability targets, they were not the bold structural reforms the country badly needed. They did nothing to promote growth and, most importantly, inclusive growth. The time for bold policy based on sound economic principles was two years ago. One can only hope that there is still time.

In collaboration with Verite Research, I have repeatedly advocated for broad-based inclusive policies that spread the burden of the crisis. Such policies, together with carefully evaluated development spending, will maximise the possibility of robust and sustainable growth and political stability. The reality has been the opposite. For example, additional tax revenue, the need for which could have been avoided by a broad-based and fair restructuring of domestic debt (DDR, or as the government coined it, DDO), is then raised by increasing VAT and increasing electricity tariffs, among other things: items that bite into the budgets of the marginalised and the rapidly disappearing middle classes. While these actions helped satisfy the accounting requirements of the IMF debt sustainability targets, they were not the bold structural reforms the country badly needed. They did nothing to promote growth and, most importantly, inclusive growth. The time for bold policy based on sound economic principles was two years ago. One can only hope that there is still time.

he writer is an Associate Professor of Economics at Oberlin College USA, and a Global Academic Fellow of Verité Research. More information can be found at

www.udarapeiris.org.)