Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 12 July 2021 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

I read the book titled ‘Range’ with much interest. I saw a clear connection of what David Epstein is trying to say and the current challenges of employment due to COVID-19. The perennial debate on the importance of generalists vs. specialists is not over. The emergence of a multi-skilled ‘T-Worker’ could be a solution to the dire needs of struggling corporates. Today’s column reflects ‘range’ in the context of resilience and revival.

I read the book titled ‘Range’ with much interest. I saw a clear connection of what David Epstein is trying to say and the current challenges of employment due to COVID-19. The perennial debate on the importance of generalists vs. specialists is not over. The emergence of a multi-skilled ‘T-Worker’ could be a solution to the dire needs of struggling corporates. Today’s column reflects ‘range’ in the context of resilience and revival.

Overview

We have heard the term ‘a jack of all trades and a master of none’. It essentially refers to someone who has a shallow coverage of a variety of areas without any depth in a particular one area. Of course, the society have got used not to consider such people too seriously as they may utter many things on many matters without any convincing manner. Instead, ‘a manager of all trades and a master of one’ could be a new way of looking at the adage. Having your mastery as the old foundation and building on a range of competencies on top of it would form a typical ‘T shape’.

The fundamental point addressed by David Epstein in his bestselling book, ‘Range’ is why generalists triumph in a specialised world. Based on success stories across many fields including sports and business, he argues for the growing need to have generalists at the helm. It resonates well with COVID-19 need of ‘3 H’ leaders of new-normal who are expected to be holistic, humble, and humane.

Range in essence

As the book tells us, plenty of experts argue that anyone who wants to develop a skill, play an instrument, or lead their field should start early, focus intensely, and rack up as many hours of deliberate practice as possible. If you dabble or delay, you will never catch up to the people who got a head start. But as David convincingly shows, a closer look at research on the world’s top performers, from professional athletes to Nobel laureates, shows that early specialisation is the exception, not the rule.

David Epstein as a science journalist examined the world’s most successful athletes, artists, musicians, inventors, forecasters, and scientists. He discovered that in most fields—especially those that are complex and unpredictable—generalists, not specialists, are primed to excel. Generalists often find their path late, and they juggle many interests rather than focusing on one. They are also more creative, more agile, and able to make connections their more specialised peers cannot see.

‘Range’, being provocative, rigorous, and engrossing, makes a compelling case for actively cultivating a kind of inefficiency. “Failing a test is the best way to learn. Frequent quitters end up with the most fulfilling careers. The most impactful inventors cross domains rather than deepening their knowledge in a single area. As experts silo themselves further while computers master more of the skills once reserved for highly focused humans, people who think broadly and embrace diverse experiences and perspectives will increasingly thrive.”

It is interesting to note how Bill Gates looks at the book: “Fascinating...I think his ideas even help explain some of Microsoft’s success, because we hired people who had real breadth within their field and across domains. If you are a generalist who has ever felt overshadowed by your specialist colleagues, this book is for you.”

Moving beyond specialisation

Moving beyond specialisation

In the book ‘Range’, David expands on the points from his previous book, ‘The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance’, in making it a more general argument against what he called ‘overspecialisation’. As he argues with evidence, more diverse experience across multiple fields is more relevant in today’s society than specialisation. In his own words, “The wicked problems of the modern world requires bridging experience and knowledge from multiple fields to foster solutions.”

Interestingly, Epstein’s views were contradictory to another best-selling author, Malcolm Gladwell, who insisted on a 10,000-hour rule for any specialisation. In preparing for a healthy debate with Malcolm, Epstein was supposed to have gathered studies that looked at the development of elite athletes and saw that the trend was not early specialisation. Rather, in almost every sport there was a ‘sampling period’ where athletes learned about their own abilities and interests. The athletes who delayed specialisation were often better than their specialised peers, who plateaued at lower levels.

In an interview with ‘the Verge’ website, David Epstein shares his candid views of the need to be more of a generalist as follows: “The 10,000-hour rule just gave it more of a common language and intensified it, basically. I really do think that Tiger Woods himself (whom Epstein writes about in the beginning of the book) helped kick this into high gear when he went on television as a two-year-old. Obviously, Tiger Woods went on to be the best golfer in the world. Nothing I wrote was meant to say this did not work, but the problem was extrapolating that to everything else that people want to do. Golf is what psychologist Robin Hogarth called a ‘kind environment’ and Hogarth set out the spectrum from kind to wicked environments.”

“The most kind environment is one where all the information is totally available, you don’t have to search for it, patterns repeat, the possible situations are constrained so you’ll see the same sort of situations over and over, feedback on everything you do is both immediate and 100 percent accurate, there’s no human behaviour involved other than your own. Whereas on the opposite side, with wicked environments, not all information is available when you must decide. Typically, you are dealing with dynamic situations that involve other people and judgments, feedback is not automatic, and when you do have feedback, it may be partial, and it may be inaccurate.”

“Most of the things that people want to do are much more toward the wicked end of the spectrum than golf. You do not know any of the rules, they are subject to change without notice at any time, and over and over. Early specialisation is not the best way to go.”

“At the end I focused on scientists and scientific research.” continues Epstein. “Scientists, to the outside world, are the epitome of specialisation in one sense, and I wanted to make sure that I included people who were viewed that way. Among these people who, compared to the population at large, are very specialised, what does it mean to have range? How do you capture the benefits of range even at the point in your career where you have specialised to a certain degree?”

It is noteworthy to mention the response from a rival. Malcolm Gladwell, the bestselling author of Blink and Outlines observed the following: “For reasons I cannot explain, David Epstein manages to make me thoroughly enjoy the experience of being told that everything I thought about something was wrong. I loved Range.”

In fact, the balancing of a specialisation with the fitting range of generalisation could be the way forward. This is what a good MBA is supposed to do with a wider opening to much diverse areas whilst the learner comes from a specialised background. I personally experienced it as an electrical engineer learning economics and marketing for the first time through my MBA. It paves the way for what is now popular as ‘T form exposure’ or ‘T workers’.

Emerging trend of ‘T-Workers’

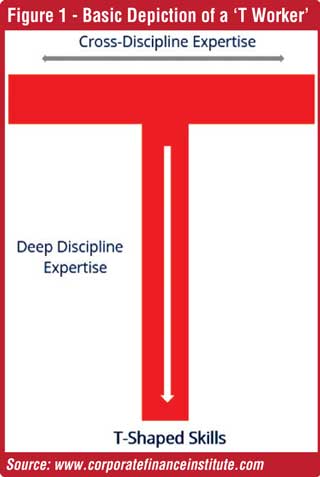

The current crisis has taught us the need to have multiple skills. When confronted with a new issue, one needs to flex the creative muscles to suit the context. Figure 1 contains a basic depiction of a T Worker.

It is interesting to note the spread of cross-disciplined expertise with a deep-disciplined expertise act as a wedge, creating a true T shape. According to the Corporate Finance Institute, the first ‘official’ reference to T-shaped skills, or a T-shaped person, was made by David Guest back in 1991. The concept gained real popularity after Time Brown, the CEO of IDEO Design Consultancy firm endorsed the idea when looking over applicants’ resumes. His view was that using the search for T-shaped skills, or a T-shaped person was helpful in building the very best interdisciplinary teams within a company. As he shown in action, it, in turn, leads to a stronger, more efficient, and potentially groundbreaking company.

Way forward

Prof. Adam Grant from Wharton Business School, one of my favourite emerging management authors had this to say on Range: “In a world that’s increasingly obsessed with specialisation, star science writer David Epstein is here to convince you that the future may belong to generalists. It’s a captivating read that will leave you questioning the next steps in your career—and the way you raise your children.”

I see the relevance of range in the local context, every time I meet a medical specialist who transformed as a successful entrepreneur. Also, it is the same when an artist engages in leading an event management company offering a total solution. It is the same when a sporting personality creates a sports academy where he/she plays a key role in expanding the range of expertise needed to run a sustained organisation.

In combatting with COVID-19, strengthening one’s specialisation with a range of general skills is needed to survive and to succeed. “The challenge we all face is how to maintain the benefits of breadth, diverse experience, interdisciplinary thinking, and delayed concentration in a world that increasingly incentivises, even demands, hyper-specialisation,” so says David Epstein leaving a range of food for thought.

(The writer is the former Director of the Postgraduate Institute of Management and can be reached through [email protected], [email protected] or

www.ajanthadharmasiri.info.)