Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 21 August 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The islandwide power outage for several hours on 17 August was a clear reminder of how much we rely on a steady supply of electricity in our homes, offices and factories.

Now imagine the much greater disruption could happen if petroleum and coal imports – essential for operating thermal power plants that generate a large share of our electricity – were to stop arriving even for a few weeks.

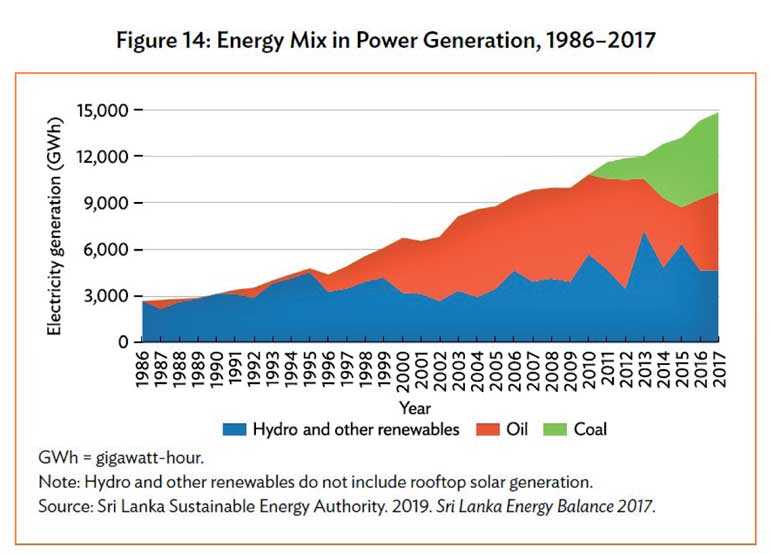

Gone are the days when most of our electricity came from hydro power, an entirely indigenous and renewable (but finite) source. An analysis of the electricity generation fuel mix between 1986 and 2017 shows how, since 2000, hydro has generated only-one third to one-half of total gigawatt-hours per year (actual share depends on each year’s rainfall, which is increasingly unpredictable due to climate change).

How to diversify and scale up sustainable energy sources to enhance Sri Lanka’s energy security? That was a life-long quest of late Dr. Ray Wijewardene (1924–2010), the maverick inventor, engineer and systemic thinker whose tenth death anniversary is being observed this week.

In the public mind, Ray was perhaps best known for building and flying light aircraft, and he was licensed to pilot fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters as well as autogyros. Despite being a high flyer in every sense of that phrase, he had his feet firmly on the ground — and sometimes in the mud. He was fond of saying, “Agriculture is my bread and butter, while aviation is the jam on top of it.”

That combination gave him unique perspectives. As a farmer, Ray took the ‘toad’s eye view’ of ground level realities; as an aviator, he also had the ‘bird’s eye view’.

Ray was renowned for his unorthodox ideas and audacious experiments. All his life he tackled problems in vital areas like renewable energy, farm productivity, land care and environmental conservation in ways that made economic and practical sense. He was never an armchair anything.

A decade after he passed away, the big problems he worked on are still there, only more acute and urgent. Sri Lanka’s new Government facing multiple challenges in the wake of COVID-19 economic fallout can surely benefit from the systemic thinking and extensive writing that Ray Wijewardene has left behind.

Path to non-dependence

Philip Revatha (Ray) Wijewardene was an outspoken public intellectual who was ever ready to discuss and debate on matters related to natural resource management and energy use. He combined the analytical precision of a Western-trained engineer with the integrated and nuanced approach of an Eastern philosopher.

And because he did not allow himself to be trapped within the narrow specialisation of a single discipline, he could ‘zoom in’ to grasp micro level details and then ‘zoom out’ to see the bigger picture.

An example from my many years of association and occasional collaboration with the visionary can help illustrate this.

“How did you come here?” was a question that Ray regularly asked visitors to his Colombo home cum office. The typical answer was: by some form of motorised transport – bus, car, three-wheeler or motor cycle.

|

Ray Wijewardene

|

“Just think about it for a minute,” Ray would urge them. “You just came here in an imported vehicle that was fuelled by imported oil…and travelling on roads paved with imported bitumen (tar)!”

He’d wait for a few seconds for that to sink in, and then ask: “Everything imported! Do you still believe we’re an independent nation?”

His vision of independence was not limited to political self-governance that Ceylon gained in 1948 (at which time he was a young man of 23). He argued that countries should aspire to be "non-dependent" in critical areas.

He explained in an essay written in 2001: “Surely, we need a firm national goal of NON-DEPENDENCE where the basics of life are concerned: food, energy and transport. Not only for strategic reasons, but for the sound reason of national pride.”

He added: “A clear definition of ‘non-dependence’ is essential for providing a direction for national development, and thereby…for national scientific research.”

Scientific research, when well anchored in such priorities, could help generate new knowledge and develop or adapt technologies for such non-dependence. He used his Board positions in public sector bodies like the National Institute of Fundamental Studies (NIFS), Coconut Research Board and the Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka to advocate for such research.

Enlightened nationalist?

Did all this make Ray a nationalist? Yes and no. Yes, he wanted his country to advance in the world and not make ends meet on foreign aid or loans – thus making him an enlightened nationalist. But no, he was not a nationalist in the widely known narrow sense of that term.

Educated at top Western universities (Cambridge and Harvard), he had had a multi-faceted career working for corporate and inter-governmental bodies in technology and development spheres. He recognised that countries were inter-dependent in the modern world: no nation could remain an island in today’s integrated and globalised world.

In his view, the term ‘globalisation’ needed to be understood as ‘global inter-dependence’. In such an inter-dependent world, countries may pursue non-dependence in key areas such as food, energy, transport and public health while also trading or exchanging in other areas.

How to achieve this balance in Sri Lanka is what he devoted three decades of his life. By then, he had gained much experience working with the United Nations (FAO) and the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) advising governments in Asia and Africa.

Growing food and energy

In Ray Wijewardene’s integrated thinking, growing most of our food as well energy was entirely within the natural and human resources of Sri Lanka. All it needed was the right mix of vision, policies and practices.

As he often said, “Sri Lanka is uniquely located within the humid and tropical regions of the world, and blessed through year-round sunshine, with year-round photosynthesis to derive year-round (plant) growth, for the sustained production of energy and of fertility.”

Ray’s vision for enhancing the energy security of Sri Lanka is definitely worth studying as Sri Lanka continues to meet its energy demands.

Ray crunched his numbers and was very concerned that Sri Lanka was importing ever-increasing quantities of petroleum for transport and electricity generation. The country was paying its hard-earned foreign exchange to buy oil – burning which contributed to global warming and also aggravated local air pollution.

Sri Lanka’s annual oil import bill varies depending on world oil prices, but it is massive. For example, in 2011 Sri Lanka imported petroleum products worth USD 6 billion, or approximately 25% of all import costs.

If anyone wants to pursue import substitution seriously, petroleum is the right place to start Ray used to say.

During the past decade after Ray’s demise, coal-fired electricity generation at the Norochcholai power plant (commissioned in 2011) has increased our dependence on another type of fossil fuel – also fully imported and even more polluting.

In Ray’s view, being addicted to fossil fuel was unhealthy and unsustainable for a country like Sri Lanka that did not have any such resources of its own. Indeed, he asked, why do we need to rely on ancient, fossilised biomass – which is what oil and coal really are – when such biomass could be grown and harvested here and now!

Pioneering dendro power

The renewable and scalable energy source he promoted the most was dendro power where electricity is generated by burning pieces of biomass harvested from fast-growing trees like gliricidia (Gliricidia sepium). Sri Lanka’s power sector experts and planners dismissed the idea, but Ray sustained his research, experimentation and advocacy for many years, often using his own funds.

With engineer P.G. Joseph, he built a small dendro power plant as ‘proof of concept’ and later drew up a national dendro plan. Their work showed how dendro plantations need not impact food production (by using only marginal lands not suited for crop farming) and can generate jobs for rural youth. An added benefit: dendro is also carbon neutral, i.e. not contributing to global warming.

The technology was researched by the Ministry of Science and Technology between 1999 and 2004. The first commercial project was piloted in Walapane by Lanka Transformers Ltd. (LTL) in 2004 with the help of Ceylon Tobacco Company PLC. While the state-owned power utility Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) has long been cynical of dendro and other renewable energy sources, the private sector has warmed up to their value.

As engineer Parakrama Jayasinghe, a past president of the Bio Energy Association of Sri Lanka, wrote in a recent article, Ray and Joseph “had the perseverance to stick to their guns, in the face of much disbelief and even ridicule by those who professed to be the ‘know all’ of the energy sector. So much so, one of the senior engineers at the CEB at that time declared to Eng. Joseph that if even one unit of electricity is produced using wood fuels, he would eat his hat. Unfortunately, he did not keep to his promise when the Walapane Dendro Power Plant was commissioned and was producing 24,000 units (kWh) per day feeding the national grid!”

Despite the naysayers, dendro power is now proven both technologically and economically; several small plants are already operated by private companies for their own needs. In 2005 the Government of Sri Lanka declared Gliricidia as the fourth plantation crop in the country (after tea, rubber and coconut).

Renewables rising

According to the ‘Sri Lanka Energy Sector Assessment, Strategy and Roadmap’ prepared by the Asian Development Bank (December 2019), there were 10 biomass-based small power producers with a total installed capacity of 26.1 MW by end 2017. Meanwhile, the Sri Lanka Renewable Energy Master Plan estimates that the country has a potential for 2,400 MW of biomass-based generation capacity. Ray’s early calculations are not off the mark!

[For context, by end 2017, Sri Lanka’s total installed electricity generation capacity was 4,180 MW of which 42% was from hydro (both large hydro and small hydro); 51% from thermal; and 7% from other renewable sources such as wind, solar, and biomass.]

Technology adaptation and scaling up of renewables with private investment requires enabling policies and regulatory reforms. Can the new Government – which has two Cabinet Ministries for power and for energy, and a State Ministry for solar, wind and grid power generation development – provide this framework? Let us hope so!

While Ray was passionate about dendro, his interest was not limited to it.

He studied and experimented with other types of renewable energy: solar, wind and mini/micro hydro. He collaborated with the Sri Lanka Sustainable Energy Authority, a state agency, and the Energy Forum of Sri Lanka, a non-profit group promoting renewable and distributed forms of energy. He also co-founded the Bio Energy Association, www.bioenergysrilanka.lk.

He urged planners, researchers and activists to aim for a mix of energy sources and solutions: “Let us not drown ourselves in the myth of dependence on just one or two (possibly-sustainable) energies: neither just hydro, nor just solar, nor just wind, nor just biomass. The developed world has provided ample evidence of the futility of such blinkered, or one-tracked, vision…”

Hundreds of men and women inspired by Ray’s thinking and tinkering are still active in Sri Lanka’s public, corporate and non-profit sectors. Ray’s key ideas and writing on sustainable agriculture, land and soil care, renewable energy, tech innovation and climate change adaptation are collected in a website that I wrote and curated in 2012, located at: http://www.raywijewardene.net.

It is time for Sri Lanka to rediscover the vision and ideas of Ray Wijewardene, a man who was ahead of his time. A time of global crisis is when ideas of this enlightened nationalist can come to the nation’s help.

(Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene first met Ray Wijewardene in the mid 1980s when he covered the engineer’s work for the local and international media. Later, they collaborated in various science communication projects – the last was on climate change for the ‘Sri Lanka 2048’ TV debate series in 2009. He was a founder trustee of the Ray Wijewardene Charitable Trust.)