Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 18 September 2024 01:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The notion that Sri Lanka’s debt sustainability is more fragile than the narrative suggests is reinforced by the IMF’s own warnings to Sri Lanka; that its debt sustainability and economic recovery remains on a “knife edge”

This article considers the weaknesses and flaws in the current trajectory of Sri Lanka’s economy and the need to reassess the path we are taking towards debt sustainability. It will present the views of professional economists that have critically evaluated the outcomes of Sri Lanka’s IMF program and debt restructuring negotiations.

This article considers the weaknesses and flaws in the current trajectory of Sri Lanka’s economy and the need to reassess the path we are taking towards debt sustainability. It will present the views of professional economists that have critically evaluated the outcomes of Sri Lanka’s IMF program and debt restructuring negotiations.

There are a number of questions to ask about the current trajectory, but we must first understand that the broad targets are all aimed at generating debt sustainability and increasing Sri Lanka’s international credit ratings so that it is able to re-enter capital markets to finance part of the country’s foreign exchange requirement. Given below are these broad targets of the IMF:

1. Primary ac surplus of 2.3% of GDP by 2025 for 3 consecutive years

2. FX debt service cover of 4.5% of GDP by 2027 until 2032

3. Total public debt to GDP of 95% by 2032

4. Reduce Gross Financing needs to 13% of GDP by 2027 until 2032

There are two ways to perceive these targets. First, we notice that it requires a sharp fiscal adjustment in a short space of time. For over a decade, the IMF had been calling on the Sri Lankan Government to engage in a revenue based fiscal consolidation. “Revenue-based” because it does not view Sri Lanka’s overall spending as the problem.

Why does the time constraint for the adjustment matter? The argument is, the longer your debt remains unsustainable, the longer it takes to get the country back to sustained periods of high growth. This makes sense; our financial flows are not consistent, we need to borrow foreign exchange. Bilateral finance is one option, but these are complex and project driven, whereas the second option, borrowing from the markets is significantly more straight forward, making the sometimes high rates and fees attractive to countries like Sri Lanka.

On the other hand, as many other economics commentators have suggested, these targets are relatively less stringent than those applied to Zambia and Ghana. Writing in the Financial Times in September 2023, Theo Maret (Global Sovereign Advisory) and Brad Sester (Council on Foreign Relations – CFR) note that “the IMF’s targets for Sri Lanka have an internal logic with the IMF’s frameworks, but they are fundamentally hard to square with the Fund’s targets for Zambia, which looks remarkably like Sri Lanka on many metrics underpinning debt service capacity”.

Sri Lanka and Zambia have similar levels of public debt-to-GDP and external debt-to-GDP but Zambia has a larger export sector and revenue to GDP of 20%, yet Zambia’s targets are much more demanding. “Sri Lanka’s targets, in essence, are the result of threshold effects induced by the sharp difference between the IMF’s two models for assessing debt sustainability — the one for low-income countries, and the one for ‘market-access countries’… but it certainly seems like the supposedly state of the art market-access model isn’t doing a good job setting debt restructuring targets for lower middle-income countries with volatile revenue and export bases.”

Sester has been following Sri Lanka’s progress through its negotiations with the IMF and creditor committees and has some key insights for Sri Lankan policy makers. Writing on the CFR website in February 2024, Sester remains doubtful that the IMF is succeeding in setting effective targets: “I am not convinced that the IMF has been doing this job especially well. It certainly hasn’t been setting targets that are consistent across cases – and it doesn’t seem that the different targets relate in any reasonable way to differences in fundamental capacity to repay. Sri Lanka, Ghana, and Zambia have some important similarities beyond all being in default.”

Like Sri Lanka, Ghana and Zambia have had public debt that is over 100% of GDP with relatively high external debt to GDP, between 50 and 60% in many instances. Sester focuses on external debt because many countries in debt distress suffer from under-diversified streams of foreign exchange inflows. Sri Lanka has a higher GDP per capita than these African nations, which places it in a different category, what the IMF categorises as a ‘market access country’ as opposed to a low income country in terms of its debt sustainability analysis (DSA) model. Sester insists however, that if “low-income implies low (external) payment capacity, all should have relatively low payment capacity… but the restructuring targets set by the IMF differ wildly across the country cases.”

An umbrella for the drowning man

Here we are reminded of the critique of global capital and “hot money” as established by economists such as Jeffrey Sachs and Joseph Stiglitz and raised at a seminar in Sri Lanka during a visit in June this year by renowned Indian Economist Prof. Jayati Ghosh and Argentina’s former Finance Minister, Martin Guzman. Ghosh and Guzman were at pains to explain that Sri Lanka’s debt distress is not unique and that many countries around the world have fallen prey to excess, cheap liquidity from western markets following stimulus spending by those governments and increased credit from their banks.

I have written previously about how, following the trend of ISB investments by the “emerging markets” of the 1990s; the last two decades have seen large funds disbursed to “pre-emerging markets” or what are now called “frontier economies”. Ghosh notes that the whole reason for distinctions between emerging and frontier economies are the fundamental weaknesses in those ‘frontier’ economies: high fiscal deficits, persistent trade imbalances, governance deficits, underdeveloped export sectors and a lack of industrialisation.

Why were such fragile economies with limited foreign exchange inflows allowed access to large sums of foreign exchange finance? Is it feasible for Sri Lanka to re-enter capital markets so soon after a collapse, without addressing these weaknesses at the core of our economy?

Sester further notes that the “IMF does not explicitly set out the path of Sri Lanka’s external public and publicly guaranteed debt-to-GDP”, for market access countries like Sri Lanka, “there is literally no assessment of Sri Lanka’s external debt in the IMF’s debt sustainability analysis and the IMF considers this a feature, not a bug”.

Thus, while Sri Lanka’s target for public debt to GDP is 110% by 2027, Ghana cannot exceed 55% debt to GDP, and external debt to GDP has a ceiling of 40%. Due to there being no explicit modelling for Sri Lanka’s external debt over the course of the IMF program, Sester makes a few assumptions. If Sri Lanka receives “$5 billion in new fiscal financing from the MDBs during the program period… and a possibility that a significant share of Sri Lanka’s past-due interest will be honoured… Sri Lanka’s $ 40 billion in external foreign currency debt seems set to rise to about $ 50 billion in 2027… Depending on the evolution of Sri Lanka’s dollar GDP, that would put external debt between 50 and 60 percent of GDP.”

The IMF has limited Zambia’s external debt service to between 14% and 18% of revenue which is around 3-4% of GDP; Ghana’s external debt service is restricted to 18% of revenue. Sri Lanka’s target for external debt service cover is 4.5% of GDP, which according to Sester works out to be around 30% of Sri Lanka’s projected revenues in 2027.

Sri Lanka has exports to GDP of 21% compared to Ghana and Zambia that have between 30-40% exports to GDP in any given year. The IMF has therefore seemingly judged that Sri Lanka is able to “support significantly more debt (versus GDP) than Ghana or Zambia, despite having a smaller revenue base” and having lower exports to GDP.

The notion that Sri Lanka’s debt sustainability is more fragile than the narrative suggests is reinforced by the IMF’s own warnings to Sri Lanka; that its debt sustainability and economic recovery remains on a “knife edge”. The IMF Debt Sustainability Analysis emphasises that Sri Lanka faces a high potential for continued debt distress, to quote its summarised assessment: “Sri Lanka is in a deep crisis, as debt is unsustainable. Deep fiscal reforms are necessary but not sufficient to address the situation in a durable manner. Contributions from creditors are therefore needed, along with new concessional financing, to restore debt sustainability. Even after a successful program and debt restructuring, debt risks will remain high for many years.”

Debt and all his friends

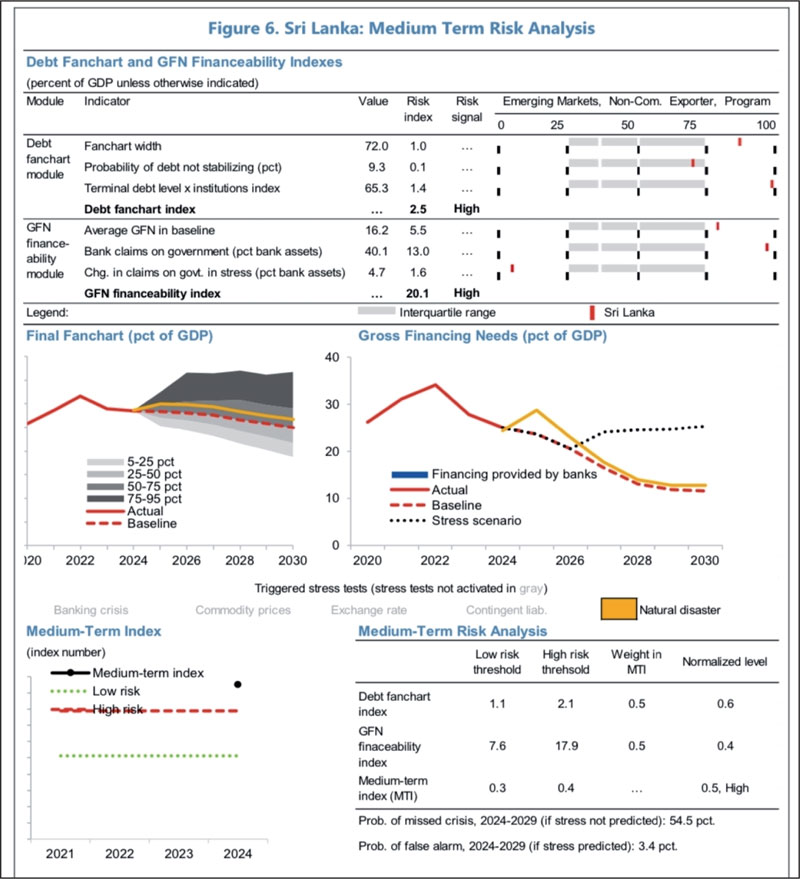

The IMF’s DSA includes a ‘Medium Term Risk Analysis’ that considers Sri Lanka’s debt and financing capabilities based on various stress scenarios and uses a debt ‘fan chart’ index and a GFN financeability index, both of which categorise Sri Lanka as ‘High Risk’ indicating that debt will not stabilise without further intervention. A fan chart is a representation of the possible variance in projections, it offers various outcomes based on deviations from a baseline scenario. Sri Lanka’s medium term sustainability is based on the total GFN and on the results of the Fan Chart Analysis.

As Sester points out, according to the IMF’s Fan Chart, “Sri Lanka was judged capable of supporting debt-to-GDP levels of above 100 percent even though it got into trouble with debt-to-GDP of around 70 percent because its gross financing need is projected to be much smaller, and IMF’s model thinks fiscal risk correlates with gross financing need” instead of the public debt stock or more importantly, the external debt stock. “Bottom line – across a host of metrics, Sri Lanka is judged able to support about twice as much debt as Ghana because it was assessed according to the IMF’s Market Access Country debt sustainability model.”

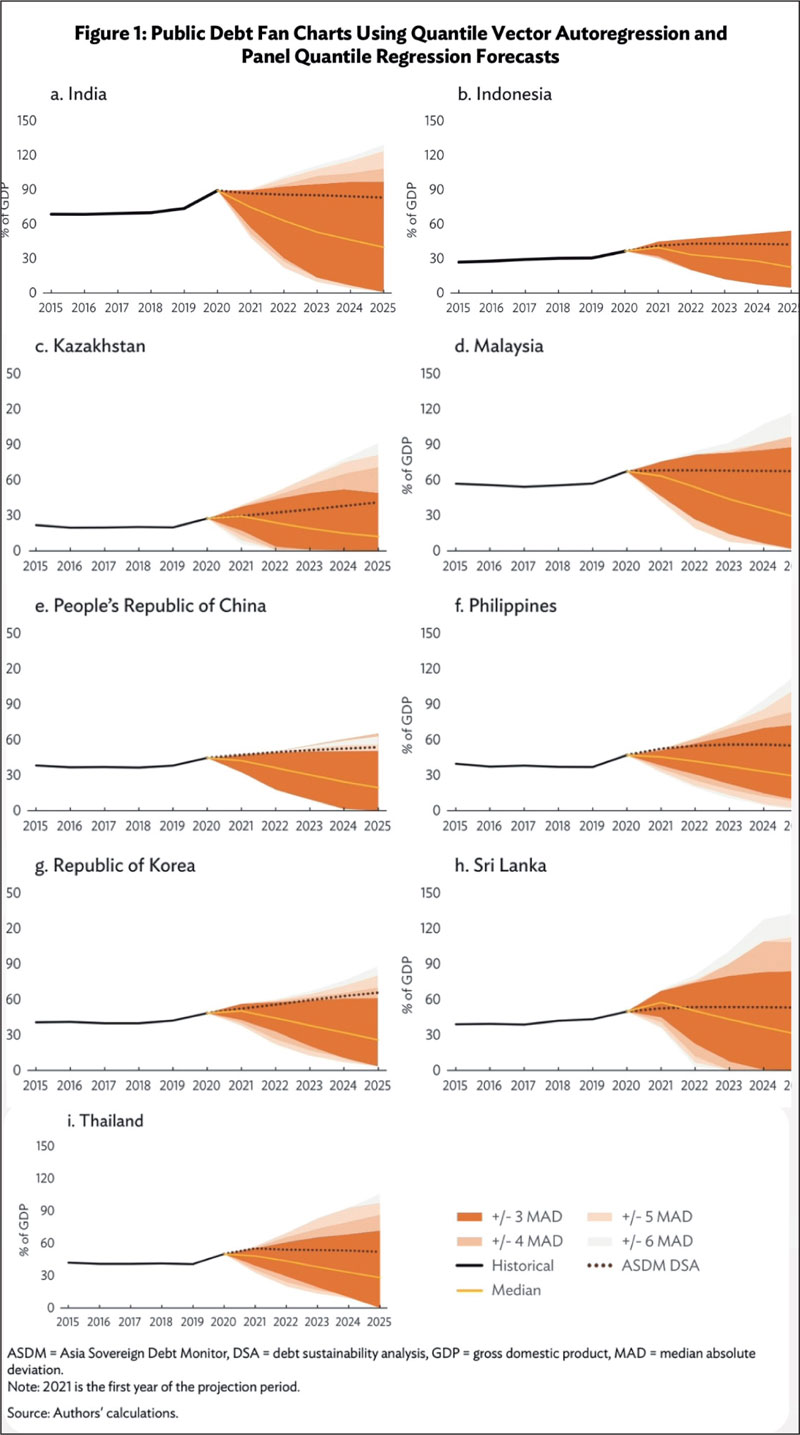

An ADB Working Paper from 2022 described a fan chart analysis as “one of the most common stochastic approaches to public debt sustainability analysis (DSA). Fan charts use historical information about the variations and correlation patterns among debt ratio determinants. They simulate a large number of random shocks, each representing a possible debt path and together fanning out as a bundle or fan. The pattern and shape of such fan charts convey information about the expected evolution of debt under uncertainty.”

In this 2022 paper, the ADB analysed debt ratios as depicted by fan charts of 9 developing member countries (DMC), including Sri Lanka. It noted that “Some DMCs, such as Sri Lanka, have large volatility in the determinants of debt, thus widening the range of debt projections, unlike others, such as Indonesia, with fan cone widths that are narrower and more stable… Sri Lanka’s fan chart has the largest fan cone width, spanning from the debt-to-GDP ratio of 1% to over 250% by 2025.” You can view the fan charts from the ADB report below, including Sri Lanka’s:

The commentary from the IMF indicates Sri Lanka’s “high level of risks associated with relatively high levels of debt and GFNs, a strong sovereign-bank nexus, and the economy’s vulnerability to large shocks. The banking sector is expected to absorb higher amounts of government debt as a proportion of its assets (now estimated at 40.1% in end-2024) compared to the first review. Sri Lanka is prone to natural disasters such as typhoons and such natural disasters could take both debt and gross financing needs to very high levels, threatening sustainability further.”

The IMF’s own commentary thus seems to reinforce the point being made by Brad Sester and Theo Maret, that the IMF’s market access model has provided targets that may not be adequate for Sri Lanka, leaving it “exposed to a high risk of a future debt crisis. The notion that Sri Lanka can safely raise $1.5 billion a year in the bond market from 2027 with public debt-to-GDP of over 100 percent and external public debt of over 50 percent is quite simply a recipe for future default – and for “new” bonds that trade badly after the restructuring”.

The authors also repeat the critique of many Sri Lankan analysts, that the IMF’s revenue targets are simply inadequate for a country with Sri Lanka’s levels of indebtedness. The IMF target of 15% is significantly lower than many countries in Sri Lanka’s income bracket.

As Sester et al contend, if Sri Lanka meets the IMF’s targets on revenue and “if you assume a 5 per cent average interest rate on Sri Lanka’s debt and a debt-to-GDP ratio of around 100 per cent, the IMF’s revenue projections imply that Sri Lanka will spend about a third of its revenue on interest payments alone…”

What’s more worrying is that the authors suggest this to be an optimistic calculation as Sri Lanka’s borrowings costs have historically averaged around 8%. At this higher interest rate, Sester et al suggest that more than half of Sri Lanka’s revenue would be gobbled up by interest payments”.

According to the IMF, only four countries will spend more than a third of their revenue on interest payments: Pakistan, Egypt, Ghana and Malawi. These countries, like most with very high debt levels, will struggle to raise large sums from the international bond markets at reasonable rates.

The question the reader must answer is, why has Sri Lanka negotiated an IMF program with so many obvious flaws? It could be speculated that Wickremesinghe is aware that further reforms and adjustments would be too challenging for a Government without a popular mandate. There are many indications in the structure of the program that this was only ever intended to be an interim program that builds a bridge to another IMF program in a few years’ time. This is the result of economic policy that fails to look beyond the confines of what Prof. W.A. Wijewardena, writing in this very journal recently, called the “neo-liberal economic policies of the Washington Consensus”.

As a member of Sri Lanka’s business community and a participant in our economy, it is essential that you are aware of the nuances of Sri Lanka’s path to stabilisation and recovery. Sri Lanka must not only improve its performance under the current plan, it must go beyond it, as Dr. Montek Singh Aluwahlia recently noted at an economic seminar in Colombo. Once Sri Lanka shows that it is on course to meet and even exceed the current parameters, it can then suggest to the IMF an alternative path that not only eases the burden on Sri Lanka’s poor and middle-classes, but actually delivers a realistic path to debt sustainability sometime in the near future.

(The writer can be contacted via: [email protected].)