Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 26 February 2024 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

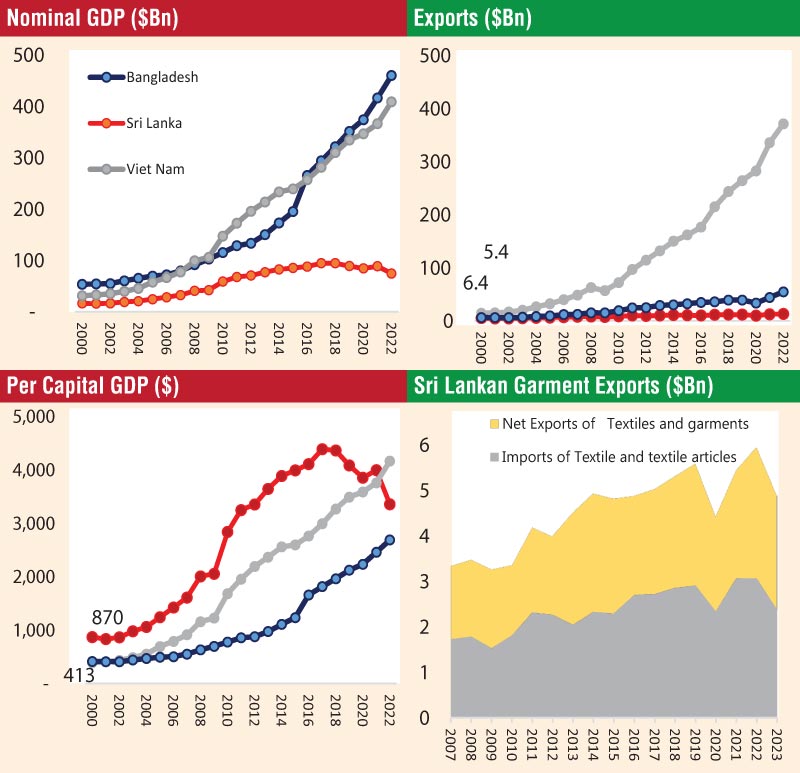

Owing to a long persisted inward-looking economic policy, large unproductive public sector and unfavourable monetary and exchange rate policies, the country failed to develop a sufficiently large export-oriented industrial sector

Sri Lanka is celebrating 76 years of independence this year, and the country is just emerging from its worst ever economic crisis which erupted in 2022. With the support of the IMF Extended Fund Facility arrangement and debt restructuring, which aims to restore long-term public debt sustainability, the country is obligated to make certain structural economic policy reforms to avoid the repetition of a similar crisis in the future.

Sri Lanka is celebrating 76 years of independence this year, and the country is just emerging from its worst ever economic crisis which erupted in 2022. With the support of the IMF Extended Fund Facility arrangement and debt restructuring, which aims to restore long-term public debt sustainability, the country is obligated to make certain structural economic policy reforms to avoid the repetition of a similar crisis in the future.

Since independence, Sri Lanka has adopted contrastingly different economic policies. The country adopted agriculture focused inward-looking economic policies of varying degrees until opening the economy in 1978. In the 1970s, Sri Lanka followed a closed economic policy. The Government in 1978 decided to embrace an open economic policy. The open economic policy encourages and prioritises private sector participation and the integration of Sri Lanka with the global economy. Since 1996, the policies adopted by the SLFP/SLPP led Governments were mostly inward looking and relied on large public spending for generating economic growth, a variant of popular Keynesian economic model. As a result of this left-centric economic policies, the public sector expanded disproportionately compared to the rest of the economy. Productive industrial and export sectors which underwent a positive start in the early 1980s didn’t receive the same facilitation from the Government. The expanding Government sector failed to generate adequate productive capacity, while imprudent policies diminished Sri Lanka’s competitiveness.

Focus on agriculture

Most Governments in the post-independence era relied heavily on facilitating and subsidising the agriculture sector in various forms. Though the economic contribution of the agriculture sector in terms of GDP remains very low (around 7%), nearly 25% of the workforce remains in agriculture. As a result, agriculture sector productivity is low and costs of production are comparatively high. Due to an overreliance on agriculture and non-modernisation, the upliftment of the population engaged in agriculture has become a challenge.

Lack of industrialisation

Many Asian countries adopted policies encouraging industrialisation and focused on the modernisation of agriculture with technology. Development of an industrial base in those countries results in large-scale labour migration from the agriculture sector to the industrial sector, as well as urbanisation. The lower labour supply into the agriculture sector demanded more capital investment, and resulted in large improvement in productivity and a reduction of the costs of production. China alone was able to raise millions out of poverty through industrialisation and by linking with global supply chains.

Contrastingly, Sri Lanka failed to focus on industrial development and was unable to link up with the global supply chain. Sri Lanka instead relied on highly subsidising the poor workforce in the agriculture sector through various support schemes including massive fertiliser subsidies and limited capital investment in agriculture, which resulted in low productivity. Since industrialisation was limited to the garment industry which developed in the late 1970s with the open economic policy, the country’s growth was subpar and a large percentage of population continues to remain in poverty. Sri Lanka missed the natural cycle of economic development that typically follows migration from agriculture sector to industrial sector, and then to service sector.

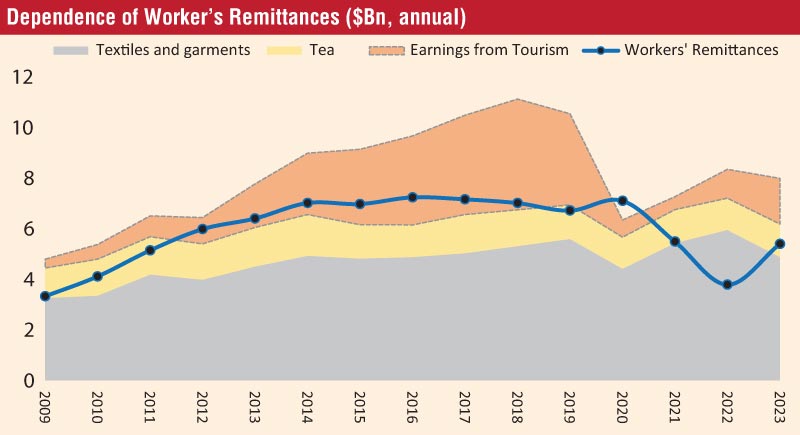

Migrant workforce

Since opportunities generated by the Sri Lankan economy were limited, and many could not find suitable employments in the country, a large population migrated to developed countries looking for better employment opportunities while the semi and low-skilled category moved to the Middle East and Asia as migrant workers. A disproportionately large migrant workforce continue to bridge the large Balance of Payment (BOP) deficit in Sri Lanka for many decades.

Unlike countries in East Asia such as Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia and lately Vietnam, Sri Lanka lacked the focus on industrialisation and couldn’t link the country with the global supply chain. Over the years, the share of country’s exports (percentage of GDP) declined and the economic growth was generated by non-tradable goods.

In economics, the goods cannot be traded across the borders and produced for consumption within the country in which they are produced, are called non-tradable goods. Countries could export tradable goods and earn foreign exchange. In contrast, non-tradable goods won’t generate export income; hence the country cannot earn foreign exchange. Economic growth in the country post 2000 was derived largely from non-tradable goods.

The large BoP deficit was funded by workers’ remittances of the large migrant workforce. Sri Lanka receives remittances from temporary migrant workers while skilled migrants generally settle in those countries and won’t contribute to workers’ remittances significantly. Empirical evidence suggests that countries, which rely heavily on migrant workers’ remittances, run into BoP problems in some point in time, since the growing deficit becomes larger to cover through remittances alone.

Quoting from a previous article published in Daily FT on ‘Exchange rate crisis: Identifying right reasons and finding appropriate solutions’ (https://www.ft.lk/columns/Exchange-rate-crisis--Identifying-right-reasons-and-finding-appropriate-solutions/4-664311). “There is a greater need for initiating necessary economic reforms for improving the structure of the economy. Sri Lanka mostly depends on female labour for foreign exchange earnings; the apparel industry ($ 4.8 b), tea industry ($ 1.5 b) and inwards remittances of migrant workers ($ 7.2 b).

Sri Lanka’s non-oil imports peaked in 2018 with imports worth of $ 18 billion while exports remain around $ 12 billion at best, including nearly $ 5 billion from export of apparel and $ 1.3 billion from export of tea. Female labour from rural Sri Lanka significantly contribute to garment and tea industries while the migrant workforce comprising significant female labour force, employed as domestic assistants in the Middle East contributes more than those two industries together.

The country’s lack of industrial focus and low economic modernisation to link with global supply chain are the main reason for economic stagnation. Sri Lanka failed to develop any industry with world recognition, except apparel manufacturing which managed to carve a niche market in the world apparel industry. The size of the apparel industry with export value of $ 5 billion is too small for an $ 80+ billion economy. Garment industry is globally cost-competitive and easily move to countries with competitive labour cost. This export oriented garment industry in the country remains around $ 5 billion mark from 2011 onwards with limited growth potential. Local value addition in the apparel industry is comparatively low with over 50% imported raw materials. Sri Lanka needs serious efforts to modernise and diversify its export base, especially linking the country’s industrial sector with the global supply chain.

While Asia is growing fast, Sri Lanka has repeatedly experienced serious economic crisis. During the past two decades, Sri Lanka couldn’t enter into any meaningful trade negotiation with its trading partners for securing free trade access to key markets. While most Asian economies focused on achieving economic growth led by industrialisation through increasing competitiveness, reforming technological education and linking the industrial sector with global supply chain, Sri Lanka relied on protectionism policies, which resulted in gradual erosion of the country’s competitiveness.

The root cause of the economic crisis is the structural deficiencies created by long-term imprudent economic policies. Economic development of a country goes through a natural transformation cycle, moving initially from the agriculture sector to industrial sector and then to service sector. Sri Lanka had failed to achieve significant headway in the industrial sector. Owing to a long persisted inward-looking economic policy, large unproductive public sector and unfavourable monetary and exchange rate policies, the country failed to develop a sufficiently large export-oriented industrial sector. While the country had failed to create a conducive environment for exports, the growth of import demand, emanated from non-tradable sector driven economic growth created a sustained large gap in the trade account.

The widening trade gap was filled with workers’ remittances from migrant workers. These inward remittances are received from temporary migrants for employment. A country can’t completely rely on workers’ remittances in the long term.

With support of IMF, the country is gradually moving out of the deep economic crisis. With heavy resistance from pressure groups and labour unions, the country is undertaking long-waited economic reforms including an ambitious privatisation program.

The country should improve the competitiveness and should aggressively pursue a strategy for gaining free trade access with key trading partners.

The duty of Government is to ensure a conducive environment to foster the industrial export sector through reforms in technological education, long-term consistent policies and facilitation of linkages with global supply chains.

(The writer is a CFA charterholder; capital market specialist and Certified FRM. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any institution.)