Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 5 May 2018 01:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

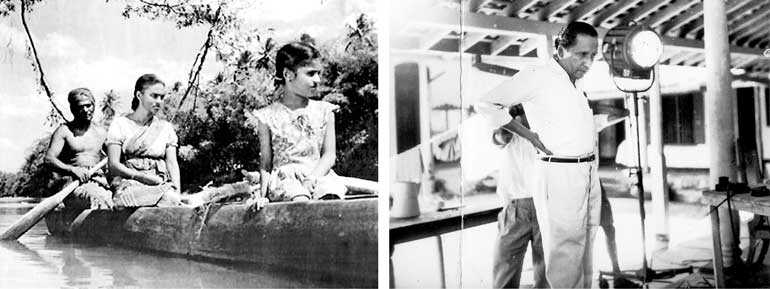

Cinematic journey of maestro

Lester James Peries – Part 1

The doyen of Sri Lankan cinema, Lester James Peries, has breathed his last. It has been my firm opinion that the master movie maker was Sri Lanka’s greatest film director.

The doyen of Sri Lankan cinema, Lester James Peries, has breathed his last. It has been my firm opinion that the master movie maker was Sri Lanka’s greatest film director.

When I began the ‘Spotlight’ column focusing on films, film personalities and film-related matters, my first article in this newspaper was about Lester and his maiden venture ‘Rekava’. Choosing to write about the maestro’s maiden feature film in my maiden article was my way of acknowledging the foremost director of Sinhala cinema.

Maestro Lester James Peries has directed 20 feature films in 50 years starting from ‘Rekava’ (Line of Destiny) in 1956 to ‘Amma Warune’ (An Elegy for a Mother) in 2006. The greatness of Lester cannot be measured by the quantity of his output. It is the qualitative nature of his films that elevated him to commendable heights.

Lester is acknowledged as the pioneer of authentic Sinhala cinema. It was he who created in every sense of the term an indigenous cinema in both substance and style. It was also Lester who first gained worldwide recognition for Sinhala cinema. Lester has become a national icon identified with the sphere of Sri Lankan cinema over the years.

In a heartfelt tribute paid to Lester by Punya Heendeniya, who starred in three of Lester’s films, the well-known actress says thus: “He (Lester) breathed cinema, talked cinema, thought cinema, dreamt cinema, produced cinema, directed cinema. He married cinema and his wife is cinema. His timeless masterpieces have left an indelible imprint on Sri Lankan and world cinema. This celebrated master considered his creations as his offspring.”

In a bid to pay homage and honour the memory of my favourite Sinhala film director I intend writing about Lester’s creations – ‘his offspring’ in the words of Punya – in a series of articles for the ‘Spotlight’ column in Daily Financial Times. I have in the past written about a few of Lester’s films and film-making and will draw from them if required. The objective now is to write about all 20 feature films directed by the great man. I must emphasise that these will not be reviews because I am not a critic. I am only a film aficionado who writes about films and film related matters.

It all began with ‘Rekava’

Just as my inaugural article for ‘Spotlight’ was about ‘Rekava,’ the first article in this series will also be on ‘Rekava’. Naturally ‘Rekava’ has to be written about first because it is the first of Lester’s films. Most of the facts that I will be relying upon for this as well as other envisaged articles would be from Lester’s earlier interviews in books and journals along with details gleaned from other related articles and reviews in magazines and newspapers.

I, myself, have utilised some of this information in some of my earlier writings and would do the same now for this article also. I do hope the effort will be successful and that this piece along with future articles will be appreciated by readers notably the numerous ‘rasikas’ of the renowned director.

The well-known director Asoka Handagama was quoted in a news story on Lester James Peries in The Hindu written by its Colombo correspondent Meera Srinivasan: “They say that Dostoevsky once said ‘we all come out of Gogol’s Overcoat’. The same way, we all came out of Peiris’s ‘Rekava,’” Handagama told The Hindu.

The impact and influence of Nikolai Gogol on the “golden age” generation of Russian writers was immense and that is what Dostoevsky’s oft-quoted remark meant. Likewise Asoka Handagama’s allusion was to emphasise the sea change brought in Sinhala cinema by Lester and the influence of the pioneering director on future Sri Lankan filmmakers. And it all began with ‘Rekava’ in 1956.

A red letter day in Sri Lanka’s cinematic history

‘Rekava’ (Line of Destiny) directed by Lester James Peries premiered 62 years ago at the Regal Theatre in Colombo on 28 December 1956. It was a red letter day in the cinematic history of Sri Lanka. ‘Rekava’ was the path-breaking film which altered the destiny of Sinhala cinema. (Though Rekava is spelled with both a ‘V’ as well as a ‘W’ in English, I am sticking to V because the original titles shown in the film spelled it with a V). Veteran journalist Mervyn de Silva, writing about ‘Rekava’ after the premiere, described it as ‘the birth of Sinhala cinema’.

The renowned journalist, critic and writer Regi Siriwardena who was later associated with Lester in writing scripts for films like ‘Gamperaliya,’ ‘Delovak Athara’ and ‘Golu Hadawatha’ was exhilarated after seeing it. He called it an ‘event of tremendous importance’ in an excellent review written by him in the Sunday Observer.

The following excerpt from that review sums up aptly the significance of the film: “And so, in the very first few moments of ‘Rekava,’ you realise you are in an entirely different world from that of the Sinhalese film up to now. We are no longer watching preposterous puppets animated by synthetic emotions; this is life itself… What Lester Peries has done is to tear down the artificial barriers that the Sinhalese film industry had erected between the screen and the real life of our own people.”

Regi and Mervyn and many others who praised ‘Rekava’ were impressed by the fact that the film dispensed with the melodramatic hallmarks prevalent in Sinhala movies since the pioneering ‘Kadawuna Porunthuwa’ or Broken Promise made in 1947. The making of Sinhala films in the early years was heavily influenced by Hindi and Tamil films made in India which were derisively described as ‘Masala movies’ or ‘formula films’. ‘Rekava’ was in that sense a departure which contrasted sharply with the usual Sinhala films.

‘Rekava’ belonged to the realist cinema category. The actors in Rekava appeared on screen as real people whom one meets daily. They spoke simply and easily in a natural way without stylised diction or expansive gestures. There were many shots where they did not speak at all with their expressions conveying emotions through the eloquence of silence. The greater part of the story was narrated – not by words and songs alone – but to a very great extent by a number of images and scenes with minimal dialogue.

Another remarkable aspect of ‘Rekava’ was that it was shot entirely on location outside a studio. Until then movies were mostly filmed in studios in India and Sri Lanka in artificially constructed sets. Also few of the filmy stories took place in a rural area. Lester changed all that by basing the film’s tale in a rural village. More importantly he filmed the village-based story in real rural surroundings with cameraman Willie Blake. Most outdoor scenes in ‘Rekava’ were shot in natural light.

Rekava

Though ‘Rekava’ is acknowledged widely as a pioneering venture with many firsts to its credit, not all the laurels heaped upon it are totally accurate. For instance, it is stated by many that ‘Rekava’ was the first Sinhala film to be shot outside studios entirely on location and that dialogues were recorded on the spot. It is also said that ‘Rekava’ was the first Sinhala movie to be filmed in Sri Lanka alone. Both these assertions are only partially correct.

The first Sinhala film to be shot on locations entirely outside a studio was ‘Gambada Sundari’ made in 1950 by Prasad Studios productions and directed by George S. Wijegunaratne. The film was first shot on 16 mm film using an Auricon ‘sound on film’ camera which recorded sound optically on film. The 16 mm film was later blown up to 35 mm and screened on 27 January 1950 at Crown theatre in Colombo. So ‘Rekava’ was not the first Sinhala film shot completely on location.

The other point made in praise of ‘Rekava’ is that the film was the first movie to be filmed entirely in Sri Lanka. Earlier Sinhala films were either wholly or partially shot in India. While ‘Rekava’ was definitely shot entirely in Sri Lanka, it was not the first movie to be so filmed.

The first Sinhala movie to be filmed completely in Sri Lanka was ‘Banda Nagarayata Pemineema’ (Banda Comes to Town) produced in 1952 by S.M. Nayagam. It was Nayagam who made cinematic history by producing the first Sinhala “talkie” ‘Kadawunu Poronduwa’ (Broken Promise) in 1947.

S.M. Nayagam who had filmed ‘Broken Promise’ and other films through his production company Chitrakala Movietone at his studio in Madurai in India had later acquired land in Kandana and constructed the Sri Murugan Nava Kala studio which later became known as SPM Studios. ‘Banda Comes to Town’ was the first film made by Nayagam in his Kandana studio. It was directed by Raja Wahab, Kashmiri an Indian national.

Making a realistic Sinhala film

After spending several years in London working as a journalist for ‘Times,’ Lester James Peries had returned to the land of his birth in 1954 and begun working at the Government Film Unit (GFU) for one-fourth the salary he got in Britain. Four years at GFU had dampened his spirits as Lester felt rather stultified presumably due to internal office politics. Besides, the creative impulse in him wanted to make a fictional feature film. There was also this growing disdain for the melodramatic Sinhala films being churned out and the idealistic ambition of making a realistic Sinhala film.

It was at this juncture that destiny played a hand in the form of kinsman Christopher Peries, a successful businessman. Lester was told that a group of entrepreneurs and professionals wanted to form a company and produce a Sinhala feature film. Lester was requested to quit GFU and come on board where he would be given a free hand. Lester would produce and direct the film. The script was to be of his choice. He could select the cast and crew. The company would purchase state-of-the-art equipment.

Lester James Peries mulled over it and decided to grasp the offer. This was the opportunity he was waiting for. Two of his colleagues also opted to quit GFU and team up with Lester. One was the cinematographer William Blake, called Willie Blake. The other was the Editor Titus de Silva who later became known as Titus Thotawatte. The trio embarked upon the challenging venture fired by the vision of making an authentic and realistic Sinhala film.

The production company was duly formed and named Chitra Lanka. The Chairman was the wealthy tycoon Sarath Wijesinghe (uncle of Upali Wijewardene). Besides Christopher Peries, the others on the Board of Directors were eminent Lawyers George Chitty QC, H.W. Jayawardene QC (the younger brother of J.R. Jayawardene), cartoonist Aubrey Collette and Douglas Fernando, an insurance entrepreneur

After much pondering Lester decided that he himself must write the story and film script for his first feature and not rely on an outside contributor. He wrote the story which was a simple narrative tinged with elements of a fairy-tale or fable. Lester wrote the script himself aided greatly by K.A.W. Perera, who later became a successful director in his own right making films like ‘Kapatikama,’ ‘Lasanda’ and ‘Bicycle Hora’. There was however much improvisation as shooting went on with new lines and words of colloquial usage being introduced.

The story of ‘Rekava’

The story of ‘Rekava’ takes place in a rural village named in the movie as Siriyala where superstition reigns supreme. The narrative in essence is about two childhood friends – a boy Sena and a girl Anula. A stilt-walker cum soothsayer reads Sena’s palm and predicts he would become a great healer. Later Anula loses her sight by accident and even the ‘Vedamahathaya’ (native physician) is unable to cure her. Anula however believes Sena can cure her by touching her eyes. She regains her sight later and is convinced it was due to Sena’s healing powers.

The story of Sena’s healing spreads and the boy’s father together with a money lender exploit this by promoting the son’s healing powers in a bid to make money. When a wealthy landowner’s son is brought for healing, Sena is unable to cure him and the boy dies. The village begins to turn against Sena. The monsoon rains fail and a drought sets in, causing hardship and misery.

The suffering villagers start believing that Sena is possessed by a devil and is bringing bad luck to the village. A ‘thovil’ ceremony to exorcise the boy is held but the devil dancers fail to detect any evil spirits in the boy. The mass mood turns ugly and at one point the landowner even tries to strangle and kill Sena. And then it begins to rain! As the torrential life giving rain pours down, the evil hopeless mood of the people transforms into that of hope and happiness. Peace descends on Siriyala.

Lester wanted to skip studios and shoot the film outdoors on location. To be really authentic, he wanted to film it in an actual rural village. This yearning to some extent had a personal dimension. Lester was from a privileged Westernised background. He was a Roman Catholic brought up in an urban atmosphere. He was more at home speaking in English rather than in Sinhala.

Lester knew very little of Sri Lanka’s villages and village life when he began making films. The decision to go to a village and shoot there was a manifestation of the deep-rooted desire to experience the village personally. While shooting the documentary ‘Nelungama’ in Mirigama, Lester had begun to discover his roots and become appreciative of the island’s cultural heritage – something his upper-middle class anglicised existence had restricted earlier.

In later life, some critics pointed out that his ‘distance’ from the social and cultural milieu in which his films were rooted was a disadvantage. But Lester compensated for this purported deficiency by infusing his creations with a tremendous amount of empathy. As Lester himself stated, “In film, the visual language is more important than the verbal. A filmmaker must master the language and syntax of the film. What is most necessary for a filmmaker is empathy, the ability to empathise with his subject.”

Shooting begins

There were two locations for the film, one at Bandarawela in the up country and the other at Wewala in the low country. Shooting began first at a location in Bandarawela. There were only two boarding houses in the area. The entire unit was housed there amidst cramped conditions. Meals were supplied from a Chinese restaurant.

The surroundings were scenic with a long winding road, grasslands, striking trees and a mountain in the backdrop. Shooting began and the opening sequences were filmed. Scenes of Sena and his friends and the virindhu song sung by Ivor Dennis for the stilt walker and the antics of his monkey were filmed to a great extent in the first few days. And then it began raining, raining, raining! It rained consecutively for 22 days! Days passed and nothing could be done.

As the pouring rain continued without abating, Lester thought of utilising the opportunity by shooting the final sequence that required heavy rainfall. So the cast needed for the final sequences were brought to Bandarawela for filming in the rain. What happened next was that the rains suddenly ceased and the sun began shining brightly, making the cast brought for the rain sequence redundant. According to Lester, the Chinese restaurant proprietor had chortled, “Lain, lain, no shooting; sun, sun, no shooting.” The weather gods had a hearty laugh at the expense of Chitra Lanka. The unit shot a few sunny scenes and returned after wasting more than 20 days.

The second location chosen was a village called Wewala close to Alawwa. Lester was familiar with the place, having filmed some scenes there earlier for the GFU. The crew and cast went to Wewala and lived there with the villagers in village homes. Lester, Willie and Titus shared one small room in a local house. The unit spent more than eight months shooting at Wewala and nearby places. The shooting schedule went awry when a chicken pox epidemic erupted, afflicting the villagers and the cast and crew including Lester. Two whole months of shooting were lost due to chicken pox.

In keeping with the assurances given to Lester, the company did let him purchase modern equipment. While in London Lester had seen the director Carol Reed use the new Arriflex camera for location shooting in his film ‘A Kid for Two Farthings’. So Lester procured the blimped, 400 ft. magazine Arriflex model from Germany. This was the first such camera to be used anywhere in Asia at that time. Lester also bought an RCA Kinevox magnetic sound recorder from the USA. This was the second of its kind to be used in Sri Lanka; the first was used by the GFU.

Since this was Lester’s first attempt at making a feature and because the concept of location shooting was something novel, the film making became a trial-and-error exercise. The weather was fine most of the time in Wewala but the problem was the overwhelming presence of crows and the sounds they made. The mikes picked up all outside sound.

The track had to be transferred regularly from magnetic to optical and sent to India for processing. A sound recordist from Madras N.B.S. Mani had been enlisted. There was no post-synching facility on location in those days. Thus Lester could not take any chances and had to shoot more than 120,000 feet of film. Nowadays of course celluloid has given way to the digital image and the art and craft of film making is completely transformed.

Handpicked cast

The cast for Rekava was handpicked by Lester. Somapala Dharmapriya was picked to play the boy Sena. The girl Anula was played by Myrtle Fernando. The role of the mother Kathrina was acted by Iranganie Serasinghe nee Meedeniya. Her husband in the film Kumetheris was played by her spouse in real life Winston Serasinghe. As is well known, both Iranganie and Winston at that time were from the elite English theatre.

Sinhala stage actors of the time like D.R. Nanayakkara, N.R. Dias and Romulus de Silva played the parts of Sooty, Podi Mahathaya and the village headman respectively. The versatile Sesha Palihakkara acted as Miguel the stilt-walker. The young couple Premawathie and Nimal were played by Mallika Pilapitiya and Ananda Weerakoon.

One of the difficulties Lester had in filming ‘Rekava’ was to make the actors, who were influenced heavily by the stage and melodramatic films, break out from that mould and act naturally. They were asked to speak normally as in everyday life instead of adopting stylised diction and intonation along with sweeping mannerisms. As shooting progressed, more and more colloquial speech was introduced into the script written by K.A.W. Perera on the instructions of Lester. Actors were also made to adopt silence at times and convey emotions through expressions or lack of expressions. Ironically the problem of sound recording on location compelled Lester to ask actors to speak out aloud at times.

Music score and songs

A remarkable feature of ‘Rekava’ was the music score and songs. When Lester was living in London, he had heard the Lankan singer Hubert Rajapaksa sing Sunil Santha’s immortal composition ‘Olu Pipila’ in a concert held at the Wigmore hall. This was in 1949. The song had a great impact on the young Lankan living in London. Years later, Lester was to recount the experience to writer-director Tissa Abeysekara. “It was a call from home and something responded from deep within my conscience,” said Lester to Tissa.

A remarkable feature of ‘Rekava’ was the music score and songs. When Lester was living in London, he had heard the Lankan singer Hubert Rajapaksa sing Sunil Santha’s immortal composition ‘Olu Pipila’ in a concert held at the Wigmore hall. This was in 1949. The song had a great impact on the young Lankan living in London. Years later, Lester was to recount the experience to writer-director Tissa Abeysekara. “It was a call from home and something responded from deep within my conscience,” said Lester to Tissa.

After listening to the ‘Olu Pipila’ rendition by Hubert Rajapaksa at Wigmore Hall, the highly-impressed Lester had inquired about the song and was told that the composition was by Sunil Santha. Apparently Lester resolved then that he must get hold of Sunil Santha if and when he made a film. So when Lester embarked upon Rekava it was Sunil Santha that he approached to compose the music. Catholic Priest, Rev. Fr. Marceline Jayakody, also known as the ‘Pansale Piyathuma’, wrote the lyrics.

Sunil Santha refused at first to compose music for a film. Lester enlisted Fr. Jayakody in his effort to make Sunil agree. Finally Sunil Santha consented with some conditions. He composed the melodies and musical score but got music director B.S. Perera to conduct the orchestra with K.A. Dayaratne as the music arranger.

The singers were Indrani Wijebandara, Sisira Senarathne, Latha Walpola, Ivor Dennis and Tilakasiri Fernando. Subsequently Indrani and Sisira got married. The song sequences in ‘Rekava’ are fabulous thanks to the words of Fr. Jayakkody, the music of Sunil Santha and the renditions by the respective singers. The picturisation of songs by Lester was enhanced by the striking camera work of Willie Blake.

‘Olu Nelum Neriya Rangala’ (Sisira), ‘Sudu Sanda Eliye’ (Indrani), ‘Mini Muthu’ (Tilakasiri), ‘Sigiri Landakage’ (Latha), ‘Anurapura Polonnaruwe’ (Ivor) and ‘Wesak Kekulu’ (Indrani) were all great hits. So too was the classic theme music composed for the showing of titles and opening scenes. Willie Blake brought out the pastoral beauty of rural hinterland through his expressive cinematography and one cannot but help recalling Mahatma Gandhi’s saying about India living in her villages.

At one stage Chitra Lanka exceeded the budget allocated for ‘Rekava’. Additional finance was procured from Ceylon Theatres which distributed the film after Sir Chittambalam and Lady Gardiner viewed some of the reels. The main editing was done in Sirisena Wimalaweera’s studio in Colombo by Thotawatte, who is credited in the film as Editor under his original name Titus de Silva. Titus however served in many capacities as an assistant director. The great thespian Gamini Fonseka too worked as an assistant to Lester for ‘Rekava’.

Gamini Fonseka’s screen debut

Sinhala cinema’s first superstar Gamini Fonseka made his screen debut in ‘Rekava’. Gamini was working as a camera cum production assistant then for Lester. His chief responsibility was to ferry the artistes and crew from wherever they were staying to the shooting location in the morning and bring them back in the evening.

It was while the film was being shot that Gamini Fonseka got a chance to be an actor. According to the script, the boy Sena played by Somapala Dharmapriya was said to have healing powers. There were scenes where afflicted people came to be cured. Due to some reason Gamini had not shaven for a few days and had stubble. Deciding to shave it off on location, Gamini hung a small mirror on a tree and took out a razor when Lester passing by told him not to shave.

“Gamini, don’t shave today. We have to shoot sick patients and with that growth you look like a sick man,” Lester said. Thus Gamini faced the camera for the first time as a patient with a towel around his neck, seeking a cure from Sena. Later in another shot he was a part of a crowd but the camera did not focus on him.

Making rain

Interestingly enough, the famous director Sir David Lean who arrived in Sri Lanka to shoot ‘Bridge on the River Kwai’ was the man who helped Lester shoot the rain scenes for ‘Rekava’.

When the making of ‘Rekava’ was in progress, Lester had a dinner meeting with Lean at the Chinese Dragon cafe in Colombo. While conversing, Lester told David Lean that he was waiting for rain to shoot the final sequences. The British Director had laughed out loud, telling Lester not to wait for rain but to go ahead and make rain with the help of the Fire Brigade. Lean also delegated his special effects and property master Eddie Fowlie to help out. Renowned Sri Lankan filmmaker Chandran Rutnam, then a very young man, was Eddie Fowlie’s assistant.

The services of the Colombo Fire Brigade were obtained. Since large volumes of water were required, the rain scene was shot in an estate belonging to J.R. Jayawardene in Kelaniya adjoining the Kelani Ganga. The fire engines pumped in the water from the river and sprayed it upwards to a height of over 60 feet using a special kind of nozzle called the London nozzle. About half-a-dozen cars flashed their headlights constantly to provide light as the shooting went on from midnight to dawn. The monsoon rain sequence was very well shown in ‘Rekava’ and forms an integral component of the film narrative.

A path-breaking venture in Sinhala cinema

As stated earlier, ‘Rekava’ premiered to an invited audience at Regal Cinema on 28 December 1956. Thereafter it was screened in 16 theatres, including Elphinstone and Roxy Theatres in Colombo. The initial reviews particularly in the English media were complimentary. The film evoked great expectations and ran well for the first week. Audiences began to dwindle from in the second week and drop drastically in the third week. ‘Rekava’ had flopped financially. The public mood had changed soon as this realistic film disappointed fans used to seeing melodramatic films of the formula variety. Also sections of the Sinhala media turned hostile to ‘Rekava’ and conducted an anti-‘Rekava’ campaign.

‘Rekava’ was a path-breaking venture in Sinhala cinema that notched many “firsts”. Among these was the singular honour of being the first Sinhala film to compete for the Palme d’Or best film award at the prestigious Cannes Film festival in France. ‘Rekava’ was screened by invitation at the 10th film festival held in Cannes from 2-17 May 1957. Lester along with Titus went first to London and edited the film again with sub-titles. The length was whittled down to 89 minutes. Rekava, dubbed in English as ‘Line of Destiny,’ did not win but Lester James Peries won significant fame for Sri Lanka known as Ceylon then by placing Sinhala cinema on the global movie map for the first time.

‘Rekava,’ the first Sri Lankan film to be shown at Cannes, did not win any award but for Lester – down in the doldrums after the film flopped – it was a morale booster. The film was received well and exhibitors bought screen rights for the Soviet Union, Poland, Germany, France and Britain. This international recognition had a positive impact back home. The film was again screened at outstation theatres for few days at a time.

Those days it was customary for cinema theatres to screen old Sinhala and Tamil films between the screening of new films. There were some theatres which screened only old films for two days at a time. ‘Rekava’ got gradually popularised in this way. I too saw ‘Rekava’ on screen for the first time at a theatre in Kurunegala in my early twenties, almost 20 years after 1956.

‘Rekava’ is now celebrated as one of Lester’s three best films along with ‘Gamperaliya’ and ‘Nidhanaya’. Lester James Peries with his ‘Rekava’ is seen as a creative pioneer in Sinhala cinema as Ediriweera Sarachchandra is perceived in Sinhala drama with ‘Maname’. ‘Rekava’ and ‘Maname’ were screened and staged in the watershed year of 1956.

As mentioned earlier, the fate of ‘Rekava’ and its director may have been different if not for the film being screened at the Cannes festival. It was that recognition which paved the way for a ‘Rekava’ renaissance. Cannes proved to be the line of destiny in Lester’s life in another sense too. It was en route to Cannes via Paris that Lester met his wife Sumitra Peries nee Gunawardena for the first time in the city of light. The couple married in 1964. That truly was for Lester and Sumitra their own line of destiny!

Next: Gamperaliya

(D.B.S. Jeyaraj can be reached at [email protected].)