Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 2 January 2024 00:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

An often overlooked factor responsible for this cycle is climate change

Growing 1.6% in the third quarter of 2023, Sri Lanka’s economy has experienced a significant shift from the dire economic crisis it faced just a year ago. The crisis led to riots and the resignation of former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, as the country grappled with lengthy power blackouts and acute shortages of food, fuel, and medicine. Defaulting on its sovereign debt repayments, Sri Lanka secured its 17th International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan in March while debt restructuring negotiations with creditors are ongoing.

Growing 1.6% in the third quarter of 2023, Sri Lanka’s economy has experienced a significant shift from the dire economic crisis it faced just a year ago. The crisis led to riots and the resignation of former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, as the country grappled with lengthy power blackouts and acute shortages of food, fuel, and medicine. Defaulting on its sovereign debt repayments, Sri Lanka secured its 17th International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan in March while debt restructuring negotiations with creditors are ongoing.

Foreign Minister Ali Sabry attributed the crisis to bad luck and bad policies, while political opponents cited corruption and nepotism. Experts also pointed to unprofitable infrastructure projects and concerns over China’s debt-trap diplomacy. These differing viewpoints agree, however, that mounting debt and a lack of foreign currency reserves created a vicious cycle that trapped Sri Lanka in fiscal crises for decades. In April 2022, the country held just $ 1.8 billion in foreign reserves, or less than one month’s worth of imports. As a nation dependent on imports of its essential goods, Sri Lanka depleted its reserves faster than it could replenish them.

An often overlooked factor responsible for this cycle is climate change. Unexpected shortfalls in domestic output due to unpredictable or extreme weather patterns and climate phenomena have accelerated the high debt and low foreign reserves cycle in Sri Lanka. As a result, it has deepened the country’s import dependence on essentials and consequently its economic and social woes.

Energy

Historically, Sri Lanka heavily relied on hydroelectric power, accounting for 43% of its electricity generation in 2021, as it offered lower installation and operating costs than solar and wind power. However, in recent years, climate change has made this vital source of energy an unreliable one. In 2021, the three largest hydropower stations in the country – providing around 40% of the total hydropower capacity – generated less than half of its maximum potential output. Rising global temperatures have accelerated water evaporation, leading to more intense storms and prolonged droughts, disrupting hydropower generation during the country’s distinct monsoon seasons. A delay in the start of the monsoon seasons has also hindered hydroelectric power output.

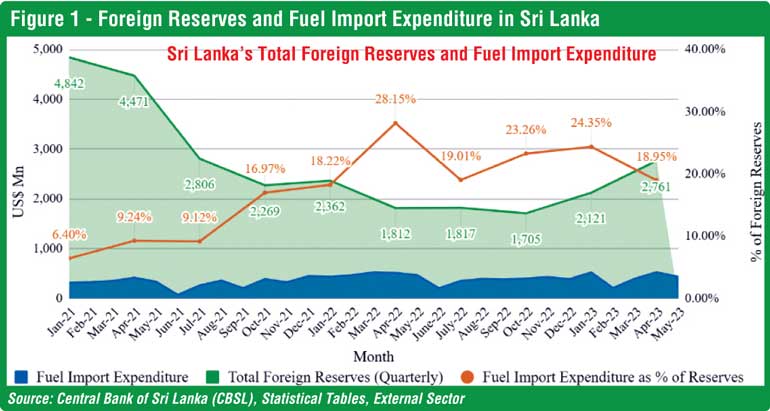

Extended periods of insufficient rainfall forced Sri Lanka to import coal, oil, and gas to compensate, with these imports comprising 49% of total electricity generation in 2021. Of Sri Lanka’s $ 1.8 billion in reserves in April 2022, $ 510 million was spent on importing fuel – or approximately 28% of its available foreign currency reserves. Sri Lanka’s reserve position was at its lowest in October and April 2022, respectively, coinciding with the inter-monsoon season.

Energy imports are at the core of Sri Lanka’s ongoing economic crisis, as the country restricted such imports at the height of the emergency, leaving schools, hospitals and nearly all of its 22.8 million citizens in the dark. Foreign assistance from countries such as India, which extended over $ 4 billion in lines of credit, enabled Sri Lanka to restart the import of fuel and essential consumer goods.

The impact of climate change on Sri Lanka’s energy sector was not factored into national policies, evidenced by domestic Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects under the Kyoto Protocol. The CDM programme allows developed countries to finance decarbonisation projects in developing countries, in exchange for ownership over the resulting emission reductions. Of the 22 CDM projects in Sri Lanka, more than half were dedicated to hydroelectric power generation. However, the diversification of the country’s generation mix would have made its energy sector more climate resilient and the CDM program would have provided the external capital needed to achieve this.

Food insecurity

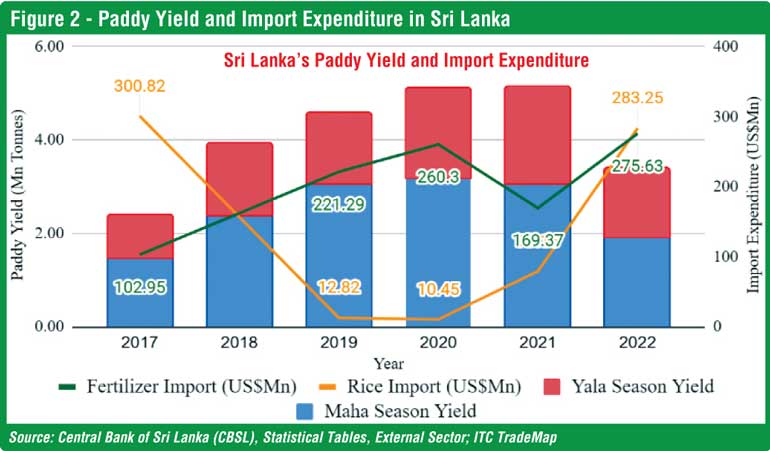

While disruptions to the water cycle have impacted Sri Lanka’s energy sector, its combination with excess heat has heightened food insecurity on the island. A severe drought in 2016 led to a 40% decrease in paddy production in 2017, while heavy rains in May 2017 further hampered crop yields. Over 600,000 people were displaced and 246 people lost their lives as a result of landslides, flooding, and heavy rain. To meet demand, Sri Lanka spent over $ 300 million on rice imports in the same year and increased fertiliser imports to boost paddy yields.

In a bold attempt to conserve foreign currency, Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa banned chemical fertiliser imports in April 2021, resulting in a 34% contraction in paddy yield in 2022 and declining tea production. Although the negative impacts of the ban represent a policy misstep rather than global warming, the latter is responsible for the instability in Sri Lanka’s food supply that led to risky policy manoeuvres.

Periods of drought or excess rain harm crops, necessitating food imports. To bounce back, fertiliser is imported to grow the domestic food supply. Ultimately, the island nation was left in a worse position, as both rice and fertiliser import expenditures ballooned in 2022, breaking away from the inverse relationship that persisted.

Climate change and pandemic preparedness

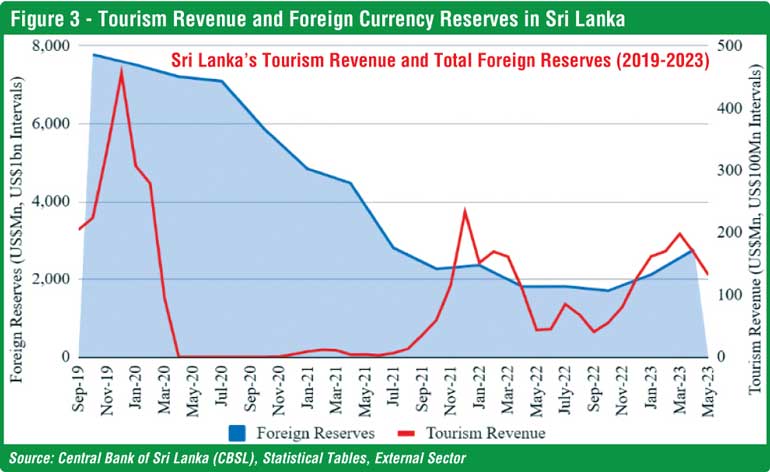

Turning from cash withdrawals from Sri Lanka’s foreign reserves to cash injections, tourism provided a major source of income. However, COVID-19 exposed the Government’s unsustainable expenditure patterns when pandemic lockdowns brought the sector to a halt. The increased cost of imports to respond to the health emergency, alongside billions of dollars lost in potential tourism revenue, depleted the nation’s foreign currency reserves before the ensuing economic collapse.

Yet another effect of climate change, pandemics are expected to occur more frequently with an even greater social and economic toll for climate-vulnerable nations like Sri Lanka. According to a report by the World Health Organization (WHO), rising temperatures inhibit the spread of zoonotic vectors and diseases, exposing more people to vector-borne diseases. In addition, land use changes that destroy wildlife habitats increase interactions between humans and animals, raising the probability of infectious diseases spreading to humans. Sri Lanka’s low urbanisation rate, with only 18% of its population living in urban areas, renders it susceptible to zoonotic spillover events, further exacerbating pandemic risks.

Policy recommendations

To address the social and economic impacts of climate change in Sri Lanka evaluated thus far, it is necessary to consider reforms to its trade policy and the energy and food sectors. Adopting a de-dollarisation strategy diversifies foreign currency use, evidenced by recent plans to transact with India in Indian Rupees (INR). Expanding this approach to other trade partners, particularly within BIMSTEC, can yield more favourable global trade outcomes than pursuing additional free trade agreements, given Sri Lanka’s limited product range and supply capacity.

Sri Lanka’s energy sector must be diversified, just as the use of its reserves must be diversified, to become more climate resilient. Improving grid efficiency and lowering the cost of solar and wind energy through advanced technologies is essential. Building on its CDM program experience, Sri Lanka can attract foreign financing for solar and wind power through the carbon trading provisions in the Paris Agreement, aided by a recent MoU with Singapore. Encouraging microfinancing for small-scale household renewable energy installations, like solar panels, can also provide crucial energy during inter-monsoon periods.

A bottom-up approach in the energy sector may also prove successful in tackling food insecurity in Sri Lanka. This may include facilitating knowledge exchange and best practices amongst farmers in the country. Growing crops that are resilient to climate change and tackling food waste are other key measures that can be taken at a grassroots level.

While raising domestic production is essential for Sri Lanka, so too is the process of domestic value addition in its non-tourism export sectors. To discourage raw material exports, authorities could raise levies on textiles and tea, the two largest export sectors by revenue. This strategy complements the low supply volumes available to Sri Lanka by targeting high-value, niche markets.

These economic policies serve as a catalyst for Sri Lanka to break the climate-induced high debt and low foreign reserves cycle that has plagued its people and institutions for decades.

(The writer is an environmental economist who conducts research and provides guidance on sustainable finance instruments and global climate policy. He joined the Sri Lankan youth delegation to COP28 in Dubai covering carbon market developments. His research positions with Sri Lankan institutions include the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies, a think tank that serves the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as well as Sri Lanka’s Permanent Mission to the United Nations in New York. Sandev has also worked with the sustainability teams at BNP Paribas in Singapore and Doha Bank in Qatar. Through these experiences, he has identified market opportunities within the financing mechanisms of various climate policies. Sandev holds a Bachelor of Arts in Economics from Yale-NUS College, with a minor in Environmental Studies.)