Saturday Jan 31, 2026

Saturday Jan 31, 2026

Thursday, 24 January 2019 00:40 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

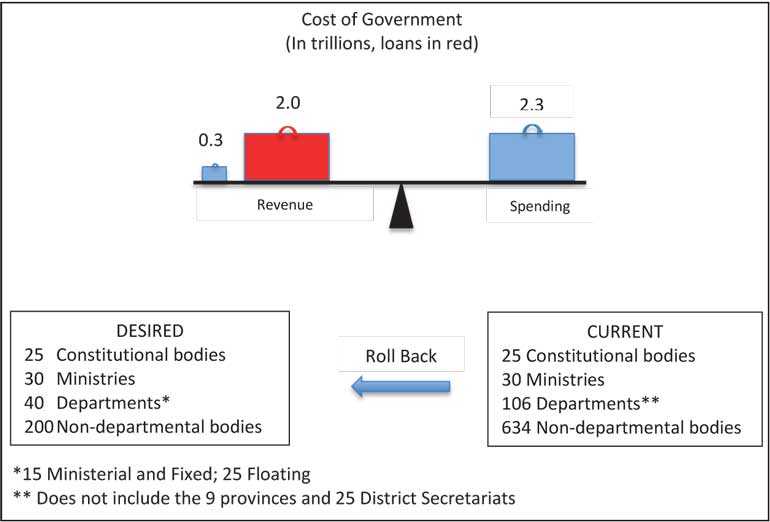

Preliminary estimates in the 2019 Budget to be presented on 5 March this year include an income of 2.5 trillion and a debt service requirements of a whopping 2.2 trillion, leaving only a net income of 0.3 trillion.

As for expenditure, the Government estimates it needs 2.3 trillion to support the 25 special accounting units or constitutional bodies, 30 ministries, 105 departments and 634 non-departmental units that constitute the Government. The department count does not include the nine provinces and 25 District Secretariats which are also spending units of the Central Government. The non-departmental units include 234 statutory bodies, and 400 public enterprises reporting to respective ministries.

In short, we are funding a 25-30-105-634 distribution of nearly 800 Government entities with borrowed money to the tune of two trillion.

Development requires deficit spending to make investments and give relief to those affected in the process, no doubt. But, are we investing as needed or are we using the money to feed a monster of a government?

Comparisons with other countries show that we indeed have a monster government with too many public entities depending on the public purse. Some preliminary benchmarking and an analysis of the allocation of departments and non-departmental bodies in cabinets present and past tells me that rolling back to a 25-30-40-200 formula is a workable ideal.

Rolling back to a smaller government

Current 25 constitutional bodies which are accountable to the Parliament include the Cabinet, the Courts, offices of the PM, President and Leader of the House, Auditor General, independent commissions and other independent bodies. I envisage the number to remain more or less the same.

Currently, the number of ministries is fixed at 30. Of those, 15 portfolios – Defence, Finance, Foreign Affairs, Home Affairs, National Planning and Economy, Physical Planning and Infrastructure, Digital Infrastructure and Digital economy, Justice, Labour, Land, Industry and Commerce, Power, Science, Technology and Research, Agriculture, Education, Environment, Health, Housing, Human Services, Cultural Affairs – can designated as ‘ministerial departments’ which are one and the same as the ministries, avoiding duplication between ministries and departments. These 15 ministerial departments would be a suitable amalgamation of any number of existing departments, for a fixed set of portfolios.

Twenty-five other departments would be distributed among fifteen other ministerial portfolios. There would be flexibility here to account for economic, social and political realities. This set of 25 departments too would be reconstituted as an amalgamation of remaining departments.

Who will roll back government to this formula, or close to, is the two trillion rupee question.

Politicians are driven by an electorate which views elections as a lottery for government jobs. Bureaucrats always seek to increase their budgets in order to increase their own power (Niskannen, 1971). Therefore, it is not surprising that our government gets bigger with each election. New units are formed to monitor the performance, but they succumb to the same fate as entities which they are supposed to monitor.

There is a Department of Public Enterprises to oversee the public enterprises. It does its best to document but its jurisdiction ends there. Sri Lanka’s Strategic Enterprises Management Agency (SEMA) was set up in 2004 with the responsibility to improve 13 public enterprises including State Banks, Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB), Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC), State Pharmaceutical Corporation (SPC), Central Transport Board (CTB), Ports Authority, Railways and plantation companies. But, it was used as a vehicle for misguided ‘green’ propaganda by its Chairman until it was shut down in 2018.

The present Government initiated a Ministry of Public Enterprises in 2015 (without abolishing SEMA of course), but it too has been a failure. The Parliamentary Committee on Public Accounts (COPA) and the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) are made up parliamentarians with so many demands on their time and a weak support system and the two are not in a position to rationalise the set up.

The annual budget is the place to start, I believe. Thanks to the initiatives by the present government, the budget format is looking more like a performance budget with outputs, outcomes and/or key performance indicators listed for each funded entity. These indicators not adequately articulated with measurable targets, but it is a good start.

Civil society in Sri Lanka has been successful in keeping the present Government more or less on track in regard to law and order, independence of public bodies and right to information. We have not been as successful in curtailing corruption. A focus on performance of government bodies is a necessary condition for that.

Performance budgeting

In public policy we learn about four basic types of budgeting: traditional Line-item budgeting, Program budgeting, Performance budgeting and Zero-based budgeting.

In Line-item budgeting allocation for each line item is based on previous year’s allocation. Whether you increase or decrease and by how much being the main consideration. In Zero-based budgeting, in theory at least, every allocation is set to zero and the allocation has to be justified each year.

In a Performance budget, each line is also broken down into performance units and allocations presented by each unit or program and its expected performance. Without the performance component, the latter would be a Program budget.

You cannot take away funding from a government department for poor performance because of job insecurity that entails, but increments can be tied to performance. However, this kind of minimal accountability will not get us far.

A gradual roll back of present government structure of 25-30-106-634 to more sane levels, with compensation for existing workforce, is essential. In order to push for that we need to understand the present structure better.

Spawning of non-departmental entities

The President recently appointed A. J. M. Muzammil, former Mayor of Colombo, to the Central Environment Authority; Reginald Cooray, a former Governor, to the Gem and Jewellery Authority; and Niluka Ekanayake, another former Governor, to State Timber Corporation as Chairmen.

Another appointment that received media attention was the naming of the brother of a minister as Chairman of the Ports Authority. All four entities are non-departmental entities which are set up to operate outside of the civil service to address various regulator or developmental issues in selected sectors more efficiently and effectively.

In reality, these entities are instruments of power for politicians. Arguments and counter arguments on the merits of these appointment is counterproductive I think. As I said before performance is the more important issue. However, given that we are supporting these entities and more on borrowed money it is time we looked beyond performance to the question of the very existence of some of these entities.

The first non-departmental entity to be formed in Sri Lanka, if I am not mistaken, was the Ceylon Tourist Board established in 1966 as a statutory body. Today we have 234 such bodies, covering almost every sector and sub sector. These bodies can indeed make government function smoother, but the problem is that the departments and even ministries have not down-sized accordingly. There are a further 400 Government-owned companies representing these same sectors. These bodies require a separate evaluation.

Redundant departments

The Cabinet of Ministers after independence consisted of 13 ministries which oversaw a handful of more departments in number. In 1966, when the Tourism Board was established, it replaced the Ceylon Tourism Bureau, a Government department. Some of those who worked in the bureau chose to leave a pensionable service to join the new board and some given the option to remain in the service.

It should have been the practice that for each new statutory body the relevant department is abolished or downsized. Judging by the current number of entities, it has not been the case. When the Central Environment Authority was established in 1980, environment related departments in the Ministry of Environment and other ministries continued to function or further expand.

New reforms require a study of the genesis and the current relevance of each every statutory body or public enterprise and the departments paralleling those to come up with a distribution close to the ideal.

Ministries becoming standalone bureaucracies

A ministry should set policy and monitor performance of implementing bodies. It need not have specialists in each of the areas under its jurisdiction. Over the years ministries have evolved into bureaucracies of their own. In addition to the usual divisions for planning, legal, administration they have additional divisions covering various sectors and sub sectors, with additional secretaries and assistant secretaries and many minions to staff each of these divisions and vehicles and drivers for senior staff. All a ministry needs is a policy planning and monitoring unit with supporting legal and financial units.

Ministries overstepping provincial authority

The Ministry of Education is a classic example of a ministry of the central government expanding into sectors where the administration is devolved to the provinces. The ministry already has under its jurisdiction the implementing bodies it requires – i.e. the Department of Examinations, National Institute of Education, Education Publication Department and the nine Directorates of Education representing each province.

The National Education Commission, a policy making body, unfortunately exists outside of the ministry irrelevant to education. The national school system is the entry point for incursion of line ministry into provincial affairs and the necessity for that system should be closely examined.

United in dysfunction

The culture of our public entities is such that these ministries, departments, statutory bodies and public enterprises seemed to be united in their dysfunction. They compete with each other for light-weight activities such as awareness and training and doling out goodies, and wasting time planning, holding and attending tamashas and waiting around for ever-late ministers.

(With apologies to exemplary Government officials with whom I have had the pleasure to work. You know who you are.)