Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday, 8 October 2020 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

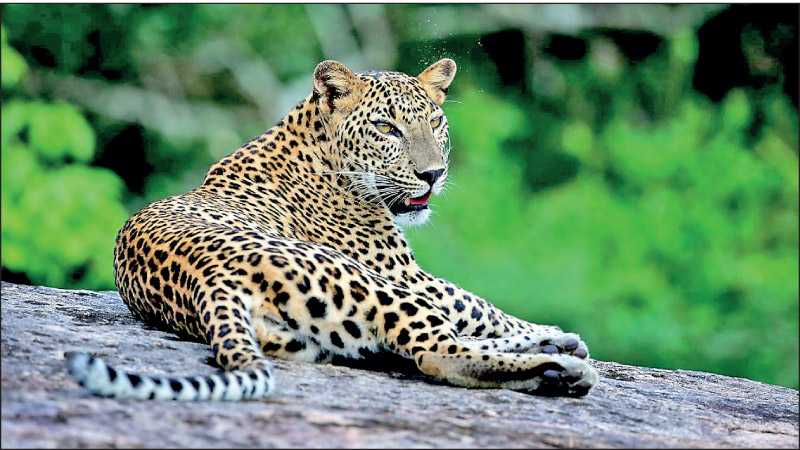

The fundamental law that governs our wild is the Fauna and Flora Act. Yet the provisions included in the Act have failed to come to terms with the realities Sri Lanka faces at this moment. The Act goes into detail on crimes against elephants with extensive punishments, however our laws do not grant specific preference to panthera pardus kotiya, the apex predator of our jungles

By Kelum Samarasena

When the police in Ududumbara stopped a trishaw for a routine check last week, what they discovered could only be termed as macabre. Later the search of the home of the suspects would lead to finding the rest of the remains of a leopard cut into multiple pieces.

Ududumbara is a sleepy hill town surrounded by the sheer beauty of Knuckles and the likelihood is high that the leopard may have belonged to this World Heritage Conservation Region. Knuckles is not known for leopards and this one could well be among the very few that live in this pristine mountain region.

It was only a week ago the workers found yet another leopard brutally shot dead with five bullet wounds in the head, at Brown low Estate in Maskeliya situated close to Peak Wilderness Reserve.

The Facebook page maintained by the Department of Wildlife Conservation shows evidence of nearly a dozen cases of arrests of suspects for killing various endangered species during the previous two weeks, and it’s just one indication of the magnitude of the terror unleashed on our last remaining wilderness regions by poachers.

It is no exaggeration to state that our systems of law enforcement and justice have failed in their mission, with regard to stemming the spate of crimes against wildlife.

Shortcomings in law

Sadly, the root cause of the tragedy may lie within the law itself.

The fundamental law that governs our wild is the Fauna and Flora Act. This has been an Ordinance from the colonial era that has been amended several times in the past with the most recent being in 2009. Yet the provisions included in the Act have failed to come to terms with the realities Sri Lanka faces at this moment.

The Act goes into detail on crimes against elephants, with a number of sections of the law being allocated for the largest mammal in our land. The punishments are extensive, including fines up to Rs. 500,000 and imprisonment up to 20 years for specified serious offenses against elephants.

However, our laws do not grant specific preference to panthera pardus kotiya, the apex predator of our jungles. Named as a protected species [Schedule II] with others including Slender loris, Jungle cat, Rusty-spotted cat, Fishing cat, Eurasian otter, Sloth bear, Grey flying squirrel, Small flying squirrel, Indian pangolin, Sambar, Barking deer and Olu muwa. The killing of a protected mammal within a reserve is punishable to the maximum of Rs. 200,000 fine and up to 10 years imprisonment for reconviction for the same offense according to Section 6[4].

Although these punishments might appear harsh enough on paper, the sad reality is that our courts have been more comfortable with fines much lower than the maximum granted by law. Instances of judgments resulting in Imprisonments for the killing of protected wildlife have been very rare.

The Act goes on to cover different types of other species as well, however with lesser punishments.

A large number of birds are named as protected species. This includes the alpine swift whose nests are frequently destroyed, particularly from the railway tunnels by criminals. Both types of crocodiles as well as many types of fish species are protected.

Incidentally, the Act has stricter punishments against crimes relating to invertebrates such as butterflies, insects, spiders, etc., an indication of the high number of cases involving the trafficking of these species in recent years. The Act does not provide protection for two species endemic to Sri Lanka –the Sri Lanka Krait snake [bungarus ceylonicus] and the Jungle fowl [Gallus lafayettii].

Wild boar, Black-naped hare, Indian crested porcupine, Toque Monkey, Grey langur, Cobra, Common Krait, Russell’s Viper, Saw-scaled Viper and over 100 species of birds are some of the many species that remain outside the protected list of wildlife.

Protected animals such as elephants and leopards are further protected by the fact that offences against them are non-bailable offences there by providing complete power to the court to refuse bail for the suspect.

Section 30[2] of the Fauna and Flora Act makes virtually any harm against a protected mammal or reptile outside a Nature Reserve or a Sanctuary an offense, resulting in the imprisonment of up to 5 years and/or a fine up to 100000 Rupees. Further, Section 67[3] of the same Act makes any offense committed under Section 30[2] an offense where bail shall not be granted by courts.

In a nutshell, Section 67[3] of the Act is emphatic on the denial of bail for an offense against a protected mammal or reptile either within or outside a Nature Reserve or a Sanctuary.

However, it would need pains to search for application of such restrictions in our courts.

Much of these punishments have been added to Fauna and Flora Act of Sri Lanka when it came under a series of amendments in 2009, by almost doubling its severity compared to previous Ordinance.

Discretion in setting fines

Still, one drawback in our law is the wider range of discretion in terms setting the fines. Although the maximum punishment appears to be substantial, the application of the full power of the legislation has been few and far between, at times with fines as little as Rs. 20,000 for the killing of a leopard.

Sri Lanka suffered massive loss of its wildlife during the previous decade. Deaths of elephants could number well over 2,500. Records show the deaths of over 100 leopards. There have been countless reports of crimes against protected species from every single Nature Reserve of the country.

Meanwhile trafficking of wildlife has been extensive, given the number of detections made. Scales of more than 700 pangolins were discovered in one capture a few months back. A huge haul of endangered wildlife in Sinharaja Reserve was recovered from a foreign tourist this year. Wildlife trafficked from Sri Lanka has been detected in neighbouring countries on a number of occasions during recent years.

Sri Lanka acceded to the CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) way back in 1979 as one of the early signatories from the region to the wide-ranging international agreement, but we are yet to incorporate the measures as agreed in CITES.

The Convention on International Trafficking of Endangered Species covers more than 36,000 such wildlife, among which there are over 200 species listed as endangered in Sri Lanka. Ironically, Sri Lanka is still listed as a category 3 nation in the CITES due to our failure in enacting laws to meet the requirements of CITES. Neither Fauna and Flora Act No. 22 of 2009, nor the Customs Act No. 23 of 2003 appear to meet the CITES requirements for preventing the trafficking of wildlife.

Category 3 includes countries whose laws are believed as not meeting the requirements for implementing CITES. Sri Lanka is one of the 35 nations in category 3. More than 141 nations come under category 1 or 2 as countries with higher levels of local legislation.

During the CITES convention held in Colombo in 2019, Sri Lanka successfully pushed for the protection of a number of species endemic to Sri Lanka or the subcontinent namely ten sub-species of lizards, Indian star tortoise, guitarfish, two species of Mako sharks, two species of white-spotted wedge fish and fifteen species of Tarantula, endemic to India and/or Sri Lanka. It’s yet another indication of the unique place Sri Lanka holds as one of the very few biodiversity Hotspots in the world.

During recent times the Sri Lanka Wildlife Enforcement Network (SLAWEN) has been set up by bringing together all stakeholders in the fight against destruction of wildlife. Sri Lanka is a member of South Asia Wildlife Enforcement Network [SAWEN] as well, which promotes cooperation among SAARC nations. But much needs to be done in order to increase the powers of enforcement of these institutions involved in wildlife protection. In a highly overburdened public sector of Sri Lanka in terms of numbers of Government servants, DWC is one with far less manpower than what’s adequate.

The fact of the matter has been the lack of teeth in our laws in effective enforcement due to highly limited scope of the punishments involved. A sophisticated poaching ring could take liberties of our existing laws, whenever their members get apprehended by the law enforcement in Sri Lanka. It has been the custom of our poachers to admit to the guilt no sooner than the charges are filed, leading to fast track punishment which may lead to ceasing of further investigations.

Law needs updating desperately

Sri Lanka desperately need to update our primary law on wildlife to meet challenges of the present times. Much of our fines fall way below the level of possible income from a sale of wildlife specimens. A killer of a leopard could earn multiple times more than the typical fines ordered by our judicial system, thus the fear of punishment hardly serves the purpose of prevention.

Though it’s true that the Act has its limitations with regard to punishments for crimes against protected wildlife, a resourceful prosecution could still utilise the Act to the maximum effect by bringing charges against a culprit under multiple sections of Act, which may lead to harsher fines.

In fact there are provisions for the Subject Minister to introduce new regulations under various Sections, without the need for time consuming legislative process.

The environmental community should endeavour to enlighten our judicial system with regard to the necessity of severe punishments since a major portion of available punishments appear to be underutilised by our courts.

It’s about time that a sustained effort is made to increase awareness among our Judiciary that the seemingly innocent looking person who has been produced for killing a leopard might have done the same many times over and that poaching is hardly a poor man’s business forced on to him due to poverty and helplessness. Poaching and the trade of wildlife stand as among the most lucrative of illegal businesses everywhere. Sri Lanka is no exception.

(Kelum Samarasena is a consultant, trainer on sustainability, and visiting lecturer for commercial law at University of Peradeniya.)