Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Tuesday, 17 August 2021 02:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Central Bank Governor Prof. W.D. Lakshman in a recent TV interview mentioned that the rupee has depreciated in the recent past due to the pandemic, although the present Government promised to maintain a stable exchange rate. But now the Central Bank is maintaining the official exchange rate at a certain level through moral suasion

Justifying the excessive currency issues by the Central Bank, State Minister Ajith Nivard Cabraal in a recent interview has stated that money printing is like drastic treatment to a major illness. But I would like to counter-argue here that money printing is wrong treatment to the ailing economy that might lead even to kill the patient!

Amidst the foreign exchange crisis intensified in recent months, the Central Bank has been attempting hard to manage the currency float so as to prevent a free fall of the rupee. Meanwhile, exporters are reported to have been lobbying the Government to depreciate the rupee to restore export competitiveness.

Amidst the foreign exchange crisis intensified in recent months, the Central Bank has been attempting hard to manage the currency float so as to prevent a free fall of the rupee. Meanwhile, exporters are reported to have been lobbying the Government to depreciate the rupee to restore export competitiveness.

The trade deficit expanded in the first half of this year despite a remarkable recovery of exports during the pandemic. This was mainly due to the substantial increase in imports of intermediate and investment goods reflecting the revival of economic activities. Consumer goods imports too rose in spite of the import restrictions that are in force.

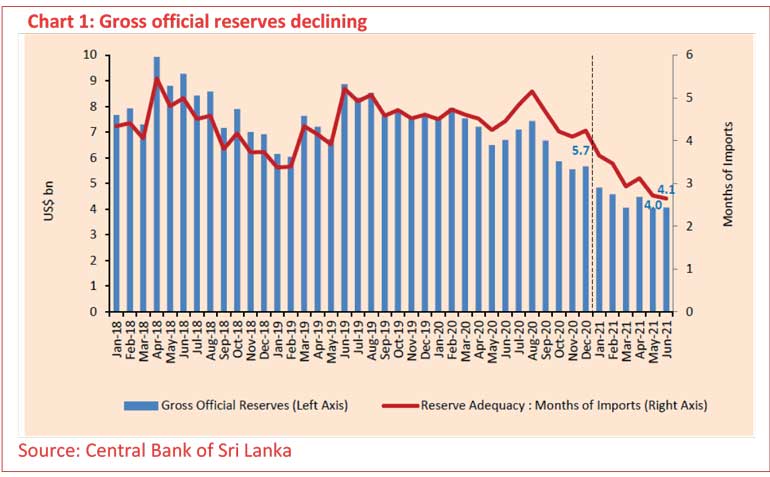

The country’s foreign reserves depleted as a result of the external payments deficit compounded by heavy foreign debt repayments, causing a severe dearth of dollars in the forex market.

Black market exchange rate much higher

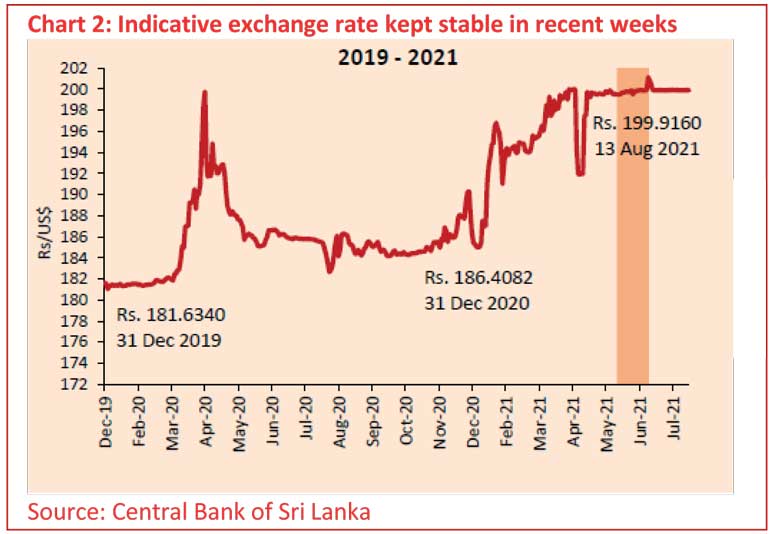

The indicative exchange rate has remained around Rs. 200 a dollar in the past couple of weeks, as per daily figures published by the Central Bank (Chart 2). But commercial banks are buying dollars from exporters at Rs. 210, and selling to importers at Rs. 215 levels, according to media reports. This happens in spite of a request made by the Central Bank to commercial banks to maintain the exchange rate at Rs. 202/204 levels.

The US dollar is said to sell in the black market at exorbitant rates of nearly Rs. 260 per dollar. Back market is a typical characteristic of a controlled economic environment.

As I predicted in this column last February, the Central Bank cannot hold the exchange rate at an artificially fixed level for long, while entertaining low interest rates and free capital flows at the same time, in terms of the “policy trilemma” or “impossible trinity” (https://www.ft.lk/columns/Policy-trilemma-poses-formidable-challenges-to-interest-and-exchange-rate-management%20/4-713226). No central bank can escape this time-tested rule.

CB adopts moral suasion to stabilise the rupee

CB adopts moral suasion to stabilise the rupee

Central Bank Governor Prof. W.D. Lakshman, in a recent TV interview on Derana’s Hyde Park, mentioned that the rupee has depreciated in the recent past due to the pandemic, although the present Government promised to maintain a stable exchange rate. But now the Central Bank is maintaining the official exchange rate at a certain level through moral suasion, he says. Moral suasion means persuading commercial banks to cooperate with the Central Bank to adopt a particular monetary policy measure.

The Governor further stated that the exchange rate is the price which affects not only imports and exports, but also various other things including people’s cost of living and the Government’s debt burden. Hence, he emphasised the need to avoid a substantial depreciation of the rupee.

It may be noted here that the Central Bank attempted to keep the exchange rate at Rs. 180 a dollar a few months ago without success.

The Central Bank’s position on the exchange rate is understandable, given the ramifications of rupee depreciation. For instance, the Government would have incurred an additional domestic currency cost of around Rs.1 billion in settling the International Sovereign Bond of $ 1 billion last month, had the currency depreciated by one rupee more.

While admitting that it is difficult to stabilise the exchange rate, Prof. Lakshman stated that export promotion is imperative to overcome the current account deficit in the balance of payments persisted over several decades.

But it is questionable how export promotion could be carried out while keeping the exchange rate at an administratively fixed level as at present, eroding export competitiveness. Currently, exporters are lobbying the Government to depreciate the rupee so as to make their exports competitive in global markets. They have requested to depreciate the rupee to Rs. 230 a dollar.

Further depreciation of the exchange rate would be unavoidable in time to come with the erosion of export competitiveness emanating from inflationary pressures manifested by excessive money growth.

Dirty float?

Sometime ago, the Central Bank sought to maintain the exchange rate at a desired level by supplying dollars from its foreign reserves. This is not possible now, as the Central Bank does not have sufficient reserves. Therefore, it exercises the tactic of moral suasion.

My former colleague Dr. W. A. Wijewardena, in a recent FT column, rightly states that the Central Bank tries to adopt an unconventional tactic that could be called ‘immoral suasion’ or arm-twisting of the forex dealers in commercial banks (https://www.ft.lk/columns/Forex-crisis-plea-for-calmness-in-national-interest-and-need-for-getting-IMF-driven-bailout/4-719992).

This kind of undue central bank intervention in the forex market is also known as ‘dirty float’.

Balance of payments deficit rising

In spite of the significant recovery of exports, the trade deficit expanded by $ 1.1 billion to $ 4.3 billion in the first half of this year from $ 3.3 billion in the same period last year on account of rising imports. Worker remittances increased while tourist earnings remained at minimal levels during the first half of the year.

In the financial account, both foreign investment in the Government securities market and the stock market recorded net outflows, and foreign direct investment continued to remain low. Hence, the overall deficit in the balance of payments rose to $ 1.3 billion in the first half of this year, resulting in a depletion of foreign reserves. The country’s usable foreign reserves are down to $ 2.8 billion, providing an import cover of only 2½ months.

Poor debt dynamics

Poor debt dynamics

The widening balance of payments deficit aggravates Sri Lanka’s debt sustainability, which is already in bad shape. A country’s public debt is considered sustainable if the government is able to meet all its current and future debt payment obligations without exceptional financial assistance or going into default. While Sri Lanka has maintained its unblemished record of debt repayment so far, as frequently claimed by the authorities, it should be noted that such prompt settlements were done through continuous foreign borrowings.

The situation has become so worse now that even foreign borrowings are constrained owing to the country’s low sovereign credit ratings. Therefore, the Central Bank is compelled to exhaust its foreign reserves for debt settlements.

Merits of flexible exchange rates

The basic idea behind exchange rate flexibility – depreciation or appreciation of the domestic currency against foreign currencies depending on market forces – is to alter the relative domestic profitability of tradable. The tradables consist of exportables and importables. The domestic prices of tradable goods are determined by the global factors and the exchange rate, plus international transport costs, tariffs, and export subsidies, if any. The prices of nontradables, largely consisting of services, are determined by domestic supply and demand.

A depreciation of the rupee results in an increase in the domestic prices of exports and imports, thereby raising the price of tradables relative to nontradables. This encourages production of exports, and discourages imports, and thereby helping to reduce the balance of payments deficit. Thus, the exchange rate works as an equilibrating tool or a shock absorber in a flexible exchange rate regime.

In contrast, under a fixed exchange rate regime, a balance of payments deficit or a surplus directly affects the country’s foreign reserve stock, and in turn, the monetary base and the money supply. Hence, the monetary authority does not have the freedom to conduct monetary policy at its will in such an environment.

In a flexible exchange rate regime, the monetary authority can exercise independent monetary policy, since external imbalances are transmitted to exchange rate movements, instead of reserve movements.

In the absence of a self- equilibrating mechanism under the fixed exchange rate regime, administrative controls such as import restrictions become necessary. Import and foreign exchange restrictions imposed in Sri Lanka since last year are a good example. Such restrictions could have been avoided, had the exchange rate is allowed to be determined by market forces.

Money creation is wrong treatment to the ailing economy

As reiterated in this column previously, excessive borrowings by the Government from the banking sector has led to a substantial increase in the money supply. Net bank credit to the Government rose by 44% over the last 12 months resulting in an increase in the money supply by 22%. The excess liquidity in the economy has raised domestic expenditure, exerting demand pressures on imports. It has also exerted pressures on the prices of nontradables and wages.

As the Central Bank has kept the rupee at a pre-determined rate through moral suasion, the role of the exchange rate as an equilibrating mechanism is lost by now. Therefore, import controls have been introduced since last year to curb the trade deficit.

Justifying the excessive currency issues by the Central Bank, State Minister Ajith Nivard Cabraal, in a recent interview with the Daily Mirror, has stated that money printing is like drastic treatment to a major illness (Daily Mirror, 2 August).

But I would like to counter-argue here that money printing is wrong treatment to the ailing economy that might lead even to kill the patient! Money creation will only aggravate economic sicknesses by widening the trade deficit and accelerating inflation.

Policy directions

Although the export sector has recovered remarkably in spite of the pandemic, export earnings still remain below the pre-pandemic levels. It is important, therefore, to consider removing the obstacles that hinder export growth. In particular, maintaining the exchange rate at an artificially fixed level is detrimental to export competitiveness. Import restrictions are only a temporary solution.

In a broader sense, it would be necessary to revisit the macroeconomic policy strategies with a fresh approach. It is understandable that drastic policy reforms cannot be adopted during these hard times, in the backdrop of the pandemic. But the policymakers need to be humble enough at least to recognise the grave economic crisis on our doorstep, instead of painting a rosy picture of the ailing economy.

No economic strategy will be successful, unless policy adjustments are carried out to rectify the macroeconomic imbalances. As reiterated in this column many a times previously, the fiscal deficit – the root cause of most economic ills – needs to be pruned down by means of revenue mobilisation and expenditure cuts.

Ideally, fiscal discipline should be enforced effectively paving the way to set up an inflation targeting monetary policy framework while permitting free float of the rupee.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and a former Director of Statistics of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, reachable through [email protected])