Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 18 August 2023 00:33 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The idea of separating wealth management from policymaking has been a practice for many centuries. Most governments have delegated public management of several core financial operations to separate professional institutions, such as, government debt to the debt management office and interest rates to the Central Bank. Similarly, some governments have delegated the management of surplus revenue from exports to sovereign wealth funds (SWFs). These SWFs, often in resource-rich countries, have succeeded in generating wealth for society and future generations.

The idea of separating wealth management from policymaking has been a practice for many centuries. Most governments have delegated public management of several core financial operations to separate professional institutions, such as, government debt to the debt management office and interest rates to the Central Bank. Similarly, some governments have delegated the management of surplus revenue from exports to sovereign wealth funds (SWFs). These SWFs, often in resource-rich countries, have succeeded in generating wealth for society and future generations.

The effective management of public commercial assets (including airports, ports, utilities, banks, listed corporations and real estate) can transform the way business is conducted, while also being a driver of productivity and fiscal space. The importance of well-governed public assets cannot be overstated, as they often operate in important sectors such as transport, energy, and finance, as well as real estate on which the broader economy depends.

A government owner of commercial assets faces many conflicts of interest, especially, with its role as a regulator of the business sectors where it also has an ownership stake. This is why commercial assets owned by the public sector are best held and governed in a separate ecosystem – a Public Wealth Fund (PWF) - away from the line ministries.

This differs from a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) such as the GIC in Singapore, primarily concerned with managing reserve liquidity, typically investing in securities traded on major mature markets. SWFs are designed to optimise a portfolio by trading securities to balance risk and returns. A PWF is a fund for managing a portfolio of operational assets with a view to maximising the assets’ value.

The managers of such a fund should be at arm’s length from short-term political influence and be able to use all the tools available in the private sector for professional management of the assets, including proper accounting, as though the fund were a listed business.

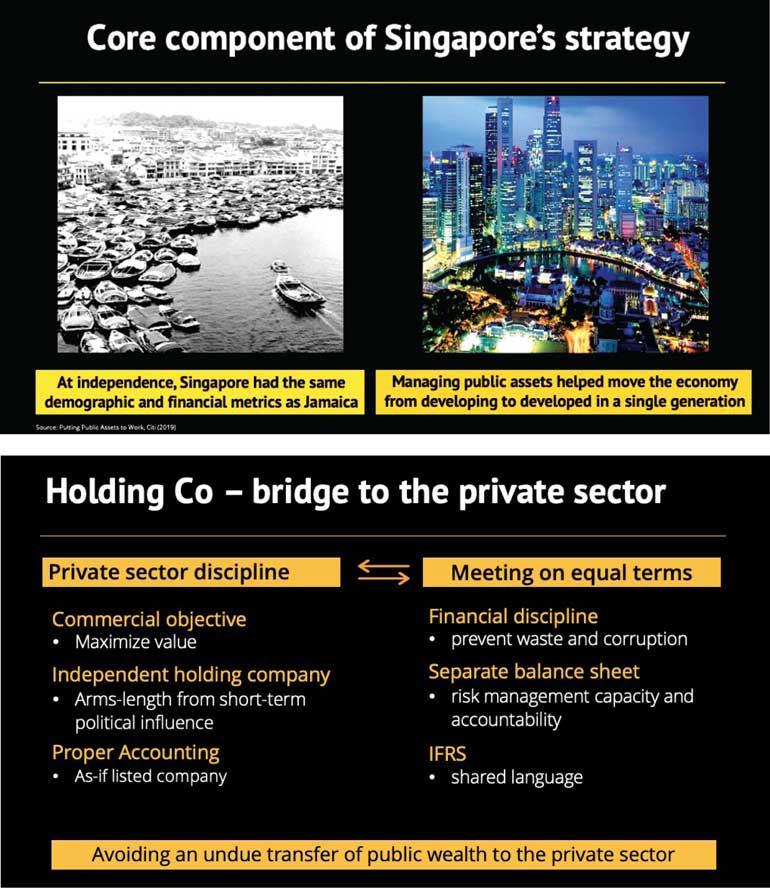

The best example is Temasek, the Singaporean PWF that has generated a compounded and annualised return of 14 % since its inception in 1974. Together with GIC the two holding companies manage a portfolio worth more than twice the GDP. The government has put in place mechanisms to safeguard the nation’s accumulated net worth (‘Reserves’) from being potentially frittered away by future governments. These Reserves have the dual role of providing a stream of investment income, as well as serving as a rainy-day emergency fund.

It was Goh Keng Swee, the Singaporean politician who served as Deputy Prime Minister of Singapore and was one of the founding fathers of Singapore, who decided to see public assets in a somewhat contrarian and different way. The tiny Asian nation had no significant resources, not even essential utilities such as water or the capacity to generate electricity. It was originally part of Malaysia, a country rich in every natural resource, from oil to agriculture and water. Separating from Malaysia in the 1960s forced Singapore, a developing economy, to rely solely on its wits to survive.

Compared to Malaysia, with which Singapore is connected by geography, history, economics, and kinship ties, the development in Singapore has taken a different track. Both countries developed institutions to manage their public assets inside wealth funds. The objective and purpose of the asset management systems differed, however, with Malaysia focused on how to divide and distribute its vast wealth among its population, while Singapore had an almost paranoid mindset to fight for survival daily. The result is that Singapore’s GDP per capita today is seven times that of Malaysia. Accordingly, a first step towards professionalising wealth management would be to separate any policy objectives and potential subsidies to focus on a single commercial objective, value maximisation – as if privately owned.

Public service obligations should be removed from public commercial assets, outsourced, and managed in a separate entity owned directly by the government department responsible for this policy area, keeping at arm’s-length from the ownership and governance of public commercial assets. A competitive procurement process, also inviting private sector competitors to operate a public service obligation would ensure that the funding with tax revenues from the budget is spent efficiently, rather than mix the funding.

Efficient financial intermediation is critical, as productivity and economic growth depend entirely on efficiently allocating capital to the most productive assets.

This is achieved partly by increasing the share of the lending carried out via capital markets and partly by decreasing the lending between government-owned banks and government-owned companies, obliging banks to turn to private companies, SMEs, and consumers instead. Moving the lending for the largest government companies to the capital market would not only improve the depth of local capital markets but also move a bilateral relationship to a competitive multilateral footing.

Any political meddling would instantly be translated into lower returns and a discount on the price a potential investor would be prepared to pay when considering investing in a public commercial asset. Hence, there exists a strong correlation between the level of private sector discipline and the yield coming from a government-owned company. Professional management of public commercial assets is not rocket science, it is done in the private sector daily. There is no reason why Sri Lanka cannot pull level with Singapore in the decades to come.

The writer is the principal of Detter & Co, an advisor to governments, investors and IFIs such as the IMF, World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. He led the restructuring of the Swedish portfolio of state-owned assets and is the author of ‘The Public Wealth of Nations’.