Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 8 November 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Buddha is the physician. Dharma is the medicine. Sangha is the nurse. This luminously lucid analogy explaining the Buddhist concept of the three jewels – Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha – is given by Professor Richard Gombrich.

Buddha is the physician. Dharma is the medicine. Sangha is the nurse. This luminously lucid analogy explaining the Buddhist concept of the three jewels – Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha – is given by Professor Richard Gombrich.

In the age of our republic, the Sangha are bent on being physicians. Some wish to be surgeons such as those in BBS and the more learned ones wish to be anaesthetists, insisting that elephants are essential to sustain Buddhist traditions.

This is the conundrum we are trapped in. Sanctimonious framers of the new constitution have become derailed trains intimidated by pseudo profundities of a priestly class cocooned in privilege from the time of our last kings of Kandy.

A paradox confronts us: Prince Siddhartha is back in the Palace.

Monastic indolence and canonical caprice have repealed and replaced the essential Buddhist wisdom – renunciation and nonattachment.

Our purpose here is not to rediscover the distilled truth in Buddhism. It is an attempt to understand how the Sinhala Buddhist Sangha, in post-independence years particularly after the 1956 political transformation, have succeeded demonstrably to run with the spiritual hare and hunt with the political hound. Their political punch drives ruling elite to call on the two principal monasteries in Kandy routinely to exchange pedestrian pities. Their presumed spiritual saintliness as custodians of the ‘sacred tooth relic’ is above and beyond public scrutiny. It allows them an undeserved and an unearned invincibility in public discourse. In the 21st Century, our Republic is taken hostage by a phantom kingdom in Kandy.

The Asgiriya Chapter fired the first volley by a clever chemistry of the thinkable and the unthinkable. ‘We do not approve of the actions of Galabodaaththe Gnanasara but his protestations have merit’. They condemned the bigot, endorsed his bigotry. In effect, the Asgiriya monastic order was signalling the government that inclusive governance was subject to boundaries that they will determine.

The three main ‘Nikayas’ have now decided to oppose Government’s constitutional reengineering and if at all undertaken to limit it to what they consider as needed.

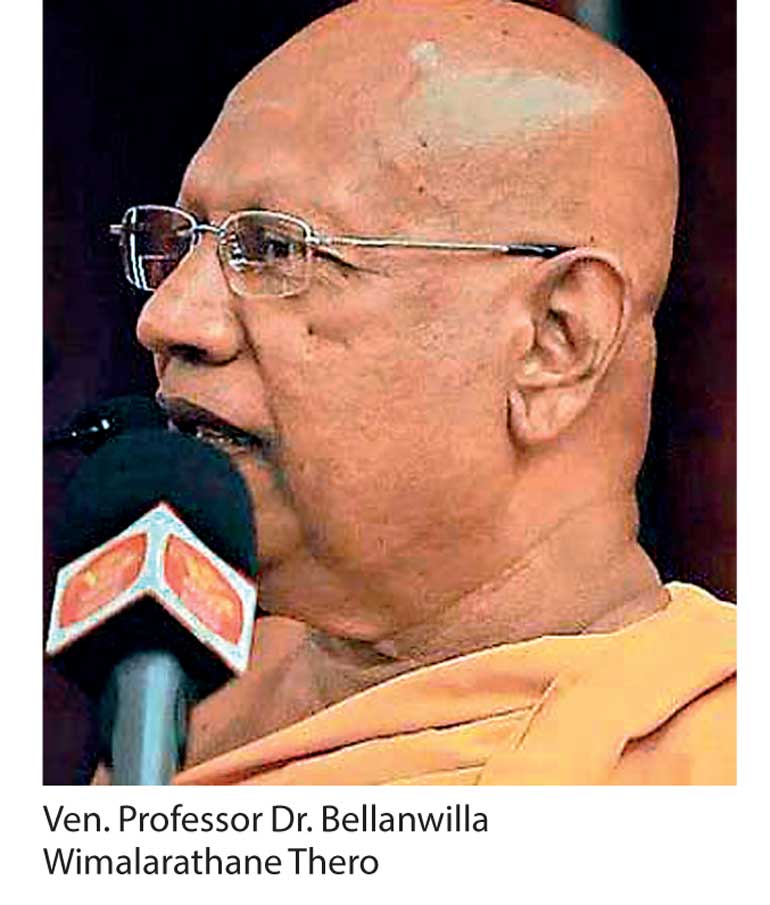

Venerable Professor Dr. Bellanwilla Wimalarathane Thero, Anunayake of the Kotte Chapter, Chief Incumbent of Bellanwila temple (film maker Asoka Handagama’s choice as the refuge of insecure minds of Colombo Buddhist middleclass in Agey Asa Aga), Chancellor of Sri Jayawardenepura University, has assumed a pivotal role of presenting a learned opposition to constitutional changes.

We are elated. Confronting literate bigotry is less complicated.

The two monasteries Malwatte and Asgiriya manifest the Sangha community in our popular mind. The sangha community of Sri Lanka is not unitary. The largest and the most influential is the Siam Nikaya which is Govigama-centric, decidedly aristocratic and feudally administered. The top layer of Malwatte and Asgiriya were manor born. The practice remains intact.

The Ramanna nikaya is a subsequent development catering to non-Govigama castes. Malwatte and Asgiriya higher echelons in the time of kings were manor born.

The Amarapura Nikaya is yet another offshoot with its origins in the south. The irony is that its federal structure escapes their blinkered minds.

The Sri Lanka Sangha is not a timeless institution either in practice or by tradition. Their claim to have preserved the Theravada tradition for two and half millennia and more is endorsed only by cagey and conniving politicians. The 2,500 years of unbroken Buddhist tradition is an idea that invaded Buddhist popular mind when the State decided to celebrate the 2,500th year in the Buddhist calendar.

Constraints of space prevents further amplification. India – the land of the Buddha – also appointed a special committee headed by Vice President Saravapalli Radhakrishnan – the philosopher. He celebrated the life of Buddha – “he was born a Hindu and died a Hindu” who reformed the caste-ridden Brahmin society.

The story of our Sangha preserving our 2,500-year-old Sinhala Buddhist heritage is not untrue. It is stating the obvious with a pinch of salt. The Sangha was integral to society and thrived or decayed parallel to the rest of society. Any religion leaves an imprint on the landscape, culture and lifestyle of the territory it dominates. Cagey clerics spin yarns on it and conniving politicians enthusiastically spread them.

‘Sangha’ in Sri Lanka – the three Nikayas Siam, Ramanna and Amarapura as we know them today – do not represent a timeless, homogenous institution of antiquity or sanctity. We need not strain ourselves to prove it. We can look around.

With a crown and kingship trapped in uncertainty, turmoil in the kingdom of Kandy did not spare the Sangha. The clerical order was in decay and neglect. The kingdom was bereft of monks who had obtained the higher ordination – Upasampada. They remained Samaneras – novice monks. Deprived of supervised discipline or peer review some degenerated to being regular householders abandoning celibacy. They wore a yellow thread or shawl around neck to signal their priestly vocation.

King Wimaladharmasuriya, the first consecrated king of Kandy, to erase an inconvenient past of fraternising with the Portuguese, and to legitimise his rule built a new palace to house the sacred tooth relic. The new King needed a functional Sangha to observe the elaborate rituals associated with the tooth relic and to perform their historical role as mediators between subjects and king. He got down monks from Rakkhangadesa – a part of Myanmar to reinstate the Upasampada order. The experiment was short-lived.

Historian Lorna Devaraja assesses the impact of the Siam Nikaya founded on the full moon day of the month Esala in 1753.

“The establishment of the Siam Nikaya was the climax of centuries of endeavour on the part of the Sri Lankan rulers and it is considered an event of singular importance in the religious, cultural and political history of the island and is recorded in elaborate detail not only in the Mahavamsa but also in several contemporary and near contemporary literary works…. “

Sinhala Buddhist society at the time was a rigid caste-based society. At its apex was a king whose divine right to  rule was incidental to his responsibility as the custodian of the Sacred Tooth Relic and the royal superintendent of the Dalada Maligawa, the Temple of the Tooth.

rule was incidental to his responsibility as the custodian of the Sacred Tooth Relic and the royal superintendent of the Dalada Maligawa, the Temple of the Tooth.

The king made tenurial grants of huge swathes of land to Malwatte and Asgiriya, the two monasteries assigned with the exclusive right and responsibility of performing the rites and observing the rituals of and related to the Temple of the Tooth.

The people – ordinary folk – worshipped the Dalada from a distance. The sanctum sanctorum was the preserve of aristocratic priests of Malwatte and Asgiriya and officials of noble birth assigned duties as required by priests.

It was an interdependent relationship between the king and the two monasteries. The priests exercised sacerdotal authority and the King minded the state. This equilibrium was lost when the King was dethroned. The British despite their undertaking to continue state patronage handed over all responsibilities to the two monasteries and one lay official the Diyawadana Nilame.

The rituals of the Palace were intended for an enshrined relic with mystical powers. One such ritual was the symbolic bathing of the relic with a special herbal preparation with fragrant flowers and scented water. The holy water from the ritual Nanumura Mangallaya was believed to contain healing powers.

Rituals of the palace were and still are expressions of homage to a sovereign. Throughout history, the sacred tooth relic was the symbol of sovereignty. In the besieged kingdom of Kandy, it was more than a symbol. It was the suzerain around which governance revolved.

To the present day, the two monasteries cling to this belief system. A Minister justifying the cost of the central highway leading to the palace in Kandy clings on to the same belief system.

The Esala Perahara mirrored the social hierarchy of the time. It was a grand choreographed event where provincial chiefs had to coalesce at the centre assuring fealty to the king.

British takeover in 1815 changed the system. They humoured the priests in the beginning but under pressure from their own missionaries were content to leave matters to the two monasteries and an official – Diyawadana Nilame.

The social reawakening of 1956 unfolded while Malwatte and Asgiriya monasteries remained in peaceful slumber. They were enjoying the tithes from land holdings, secure in the knowledge that by birth and family tradition they were the custodians of the symbol of the nation’s sovereignty.

It took a little longer for them to parlay it for a real political punch.

The serious political transformation of the system occurred when Nissanka Wijeratne, civil servant and Sinhala Buddhist activist, contested for the position of Diyawadana Nilame.

It was a curtain raiser for a subsequent foray into national politics. The then Prime Minister devoutly Buddhist, devotionally feudal, fielded a relation with a superior manorial pedigree.

He lacked the poise and punditry of the historian civil servant Nissanka Wijeratne, whose election as Diyawadana Nilame irretrievably politicised the institution in our representative democracy. The controversial contest propelled the two Mahanayakes into political prominence. If they had any influence on the election of the lay official, now they became indispensable arbiters.

Soon after, the then Leader of the opposition J.R. Jayewardene used the Maha Maluwa as the venue for a satyagraha with the permission of the Diyawadana Nilame.

When the police dispersed a LSSP protest in 1991 held with no permission from temple authorities, Bernard Soysa filed a Fundamental Rights petition on the grounds that the Maha Maluwa was a public space.

The Supreme Court ruled that the Maha Maluwa of the Dalada Maligawa was a place to which the public had access for the purpose of worship and it could not be treated as a public place for the purpose of holding a satyagraha by persons standing together in a single line and displaying posters and placards and sometimes shouting slogans or other vociferous protests. Satyagraha was a political event for which no implied permission can be presumed in relation to the Dalada Maligawa and express permission would be required for the purpose.

President Premadasa chose the Octagon of the Palace to take his oath as President. He fixed a golden canopy over the main shrine.

Historian and Sinhala scholar Anuradha Seneviratne was consulted over its official Sinhala nomenclature. He called it a ‘Runviyana’ and got into bad books of the President. A mischief maker had informed the President that the term ‘viyana’ had a caste connotation.

We must reframe the nation’s sovereignty and traditions attached to its expression in the age of the republic.