Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Wednesday, 17 April 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

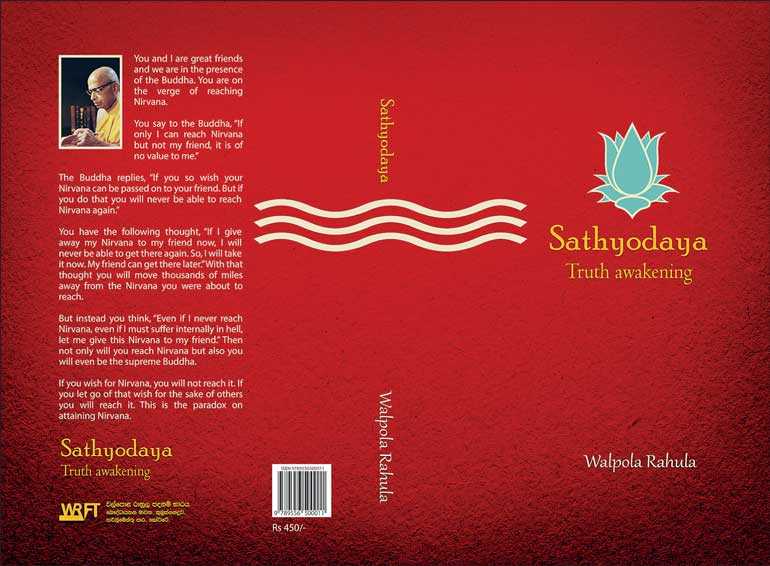

‘Sathyodaya’ written by Venerable Walpola Rahula may be introduced as the key to free thinking.

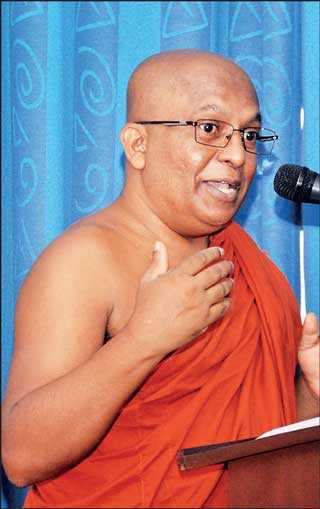

Venerable Galkande Dhammananda, the only Monk pupil of Venerable Rahula, in his introduction to ‘Sathyodaya’ says that free thinking is not an ability gained easily through habit. Proper direction and guidance is required to develop this skill. Though the physical body can be easily trained to perform a task, he says that the same cannot be said about training the mind.

develop this skill. Though the physical body can be easily trained to perform a task, he says that the same cannot be said about training the mind.

He goes on to say that progressively cultivating human understanding and judgement through reasoning is a challenging task and that Venerable Rahula articulated how this may be done in many books he wrote, and his book ‘Sathyodaya’ or ‘Truth Awakening’ epitomised his approach to how Buddhists should practice Buddhism as Buddha taught.

The original Sinhala version of this book was written by Venerable Rahula during the period 1933-34 or about 85 years ago as a series of articles teaching Buddhists how to think. These were compiled into a book and published in 1992. This book has now been translated to English. Venerable Rahula points out many false interpretations of the Buddha’s teaching as well as using Buddhism for personal gain and classifying people according to their birth by the Buddhist clergy themselves.

The question today, as it was when ‘Sathyodaya’ was published as a book in 1992, is whether the society has advanced beyond the misrepresentations, and falsehoods to a more progressive one based Buddha’s teachings as clearly articulated 85 years ago by the Venerable Rahula.

‘Sathyodaya’ as seen by this writer is about values. Values may lead to the truth. If values are not based on Metta and loving kindness to each other and every living being, it is difficult to imagine how one could see the truth. A false sense of values could easily deceive us into believing we are on the right path to the truth. Venerable Walpola Rahula’s ‘Sathyodaya’ examines these values and gives a sense of where we are with values today and where we can be with values based on the Buddha’s teaching.

This is not to say that the values of those who practice numerous Ahmisa Pooja as against Prathipatti Pooja are any less than those who practice the reverse. One person cannot and should not judge another’s values. Besides, one has to take into account the cultural context of a value system although some may take the view that there is a universal truth regarding values and that a cultural context cannot be subsidiary to that universal truth.

Then of course one can question and argue and debate the universal truth itself. Buddha’s teaching in this respect is very clear. He articulated a path towards a universal truth that he himself had travelled and realised.

He however did not advocate blind adherence to his attainment and subsequent teaching but self-reflection, and practice sans attachments and desires.

|

Ven. Galkande Dhammananda |

If one were to look at the influences that a common man (or woman) is subject to today, it is extremely difficult for such a person to decipher the truth from the untruth. For many such persons, the Buddha Sasana is what the influential Buddhist Monks amongst them represent. While it is unfair to generalise the behaviour of Buddhist Monks, it is the behaviour of some Monks that has come to represent an increasing norm amongst the Sangha about their worldliness and deviation from the teachings of the Buddha. These influence our value system.

We have seen the unBuddhistic stridency and racism of some Monks allegedly fighting for a “cause”. We witness all around us the opulence of some Monks. We see around us the open depiction of caste differences amongst the Monks, with the spectacle of Monks from one sect being given higher seats than what had been given to Monks from other sects. Of all things, this spectacle was at the launch of the campaign to list the Tripitakaya as a World heritage!

We are made to believe that some Monks have families and at times several female partners. Be that as it may, or may not, the issue here is the influence that Monks who behave contrary to the teachings of Buddha have on the ordinary Buddhist populace and how they influence and change the value system of such ordinary folk.

Today, there are many ordinary people who are being led to believe that Buddha was born in Sri Lanka. The issue here is not about the birth Nation of Buddha, but the fact that his birth place rather than his teachings has become the focus for many ordinary people. Influences have also come from some Monks who reportedly are claiming that they have realised the Truth or attained the state of an Arahath while basking in opulence.

More than 60 years ago, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike strode to power with his political platform promising the era of the common man. His political message was that the “common man” was trapped in Colonial subjugation firstly by the Colonialists themselves and after Independence, by those to whom power was transferred, one might say very peacefully, who carried on the traditions and practices of their former masters and who were referred to as the “Brown Shahibs”.

Bandaranaike successfully marshalled the five forces, Sangha, Veda, Guru, Govi and Kamkaru against the rule of the “Brown Shahibs” and won a very handsome political victory. It is not the intention here to do a critique of Bandaranaike or his policies, but to draw a parallel (of sorts) between the common man’s plight, then, and now, within the context of Venerable Walpola Rahula’s ‘Sathyodaya’.

From a Buddhist practice context, the common man is trapped within the practices of the institutional arms of Buddhism and what they present as the way to respect Buddha, the Buddha Sasana and the Sangha, and acquire merit.

The common man’s existential vulnerabilities are nothing new and even Buddha himself realised this and was reluctant initially to talk about the path to the truth. Not many amongst the populace would have been able to grasp the essence of Buddha’s message then, as they would be finding difficult to grasp it today.

The avenues available today for sensual pleasures of the five senses, and the mind, are perhaps far greater than during Buddha’s time making it even more difficult now, than then, to focus and live one’s life in keeping with Buddha’s path to the truth.

Human vulnerabilities of the mind and even the body, not just that of an individual, but even a loved one of an individual, require some anchoring mental support as a person adrift in a river would be seeking an anchor like a branch of a tree to prevent being drowned. Many people are drawn to Buddhist rituals as they are the mental anchors that give them temporary mental solace and protection.

The issue is not about such basic human wants, but about the exploitation of such wants by institutions which markets rituals for their survival and prosperity rather than as a means of providing the anchors people are looking for in their hour of need.

This writer would like to suggest that Venerable Walpola Rahula’s ‘Sathyodaya’ has to be studied in this context and not as a teaching that does not consider the anchoring support people look for in their moments of need. The challenge for Buddhist Monks, Bhikkunis, lay preachers and ordinary folk is to find a way to understand human fallibilities in their moments of need, and adapt some ritualistic practices with simplicity, mindfulness and the tenets of Buddhist principles such a Metta, Karuna, Muditha and Upeksha. The exploitation of human needs in times of vulnerable situations faced by them must stop and should be exposed for what they are.

A way has to be found as to how an anchor could be provided to anyone who is in need of an anchor without the excesses that are prevalent today and the myths that are propagated to support such excesses.

In this sense, one has to find a middle path between some basic ritualistic practices and bringing mindfulness to such practices, and the excesses that appear to send a message to ordinary people that largesse gives you more merit, that offerings to Buddhist Monks who are already endowed with far more than what they need, is more meritorious than giving a meal to a human being or even an animal who is starving.

Finally, readers should question whether ‘Sathyodaya’ is only about just reading it or whether it should be about practising Buddhist principles to the best of our ability and making a change, inwardly first and then sending a vital message to the external world by example. Many of us are quite aware of the truths contained in the book. We have been and still are in some sense, looking at these truths in abstract. We should live the truth to the extent possible. This is what Venerable Rahula presents in his great treatise on Buddhist principles.