Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 2 April 2025 00:24 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

ABC Instagram post

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC) story, “Is your tea ethical? – The uncomfortable truth behind your cup of tea,” examines whether Sri Lanka’s tea brand meets ethical and sustainability standards. However, the investigation only targets Plantation Companies (PCs) and their compliance with international certification requirements. While this focus may seem reasonable at first glance, it fails to acknowledge that PCs only contribute to about 23% of Sri Lanka’s total tea production. The report, on the other hand, generalises its findings to represent the entire “Ceylon Tea” industry, which presents a skewed perspective, relying on selective reporting rather than delivering a balanced analysis.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC) story, “Is your tea ethical? – The uncomfortable truth behind your cup of tea,” examines whether Sri Lanka’s tea brand meets ethical and sustainability standards. However, the investigation only targets Plantation Companies (PCs) and their compliance with international certification requirements. While this focus may seem reasonable at first glance, it fails to acknowledge that PCs only contribute to about 23% of Sri Lanka’s total tea production. The report, on the other hand, generalises its findings to represent the entire “Ceylon Tea” industry, which presents a skewed perspective, relying on selective reporting rather than delivering a balanced analysis.

Small and medium-scale tea cultivators, often referred to as small tea growers (STGs), play a pivotal role in Sri Lanka’s tea industry. As per a 2023 report, STGs contribute approximately 77% of the country’s total tea production. This substantial contribution underscores the importance of small and medium-scale cultivators in maintaining the quality and reputation of the “Ceylon Tea” brand in the export market.

The ABC documentary gives a sweeping narrative about the Sri Lankan tea industry—without fully exploring the complexities of the sector.

Television stories have long been regarded as a pillar of truth, delivering breaking news and investigative reports to audiences worldwide. However, as the demand for engaging content grows, so too does the temptation to shape narratives in ways that may not fully reflect reality. A method sometimes employed by news outlets is the selective framing of stories—choosing specific events, locations, and testimonies to create the illusion of a widespread crisis or trend. This approach can distort public perception and, in some cases, manipulate opinion rather than inform it.

Cherry-picking in television journalism is a selective use of facts that support a predetermined conclusion while ignoring contradicting evidence. Instead of presenting a well-rounded analysis, producers can focus on extreme examples or isolated incidents that align with their editorial stance. And viewers must keep their eyes and ears open when news is disseminated in mainstream or even social media, to determine what to believe and what not to.

A complex industry

There is no doubt that the tea industry in Sri Lanka is vast, and the economy built around this simple leaf is highly complex. One could argue that condensing such a subject into a 28-minute documentary, such as what the ABC did is challenging, but that does not excuse a lack of fairness, accuracy, and balance. When these elements are missing, the cost falls on those who are directly dependent on the industry and this goes right down to the tea small holder.

In the story of Naomi Selvaratnam, which was broadcast on 5 March of this year, the aim was clearly established from the beginning, highlighting Sri Lankan tea brands she discusses.

“On the boxes of the big tea brands, there’s a promise that their product has been ethically and sustainably produced wherever it’s grown. But is it true for tea grown here in Sri Lanka?…We are heading deep into the tea fields to see whether the labels live up to their promises.”

This writer would like to point out that she says ‘wherever it’s grown’, and connects it to the ‘tea grown in Sri Lanka’.

But as the story unfolds, we see how this so-called investigation becomes increasingly disconnected from reality, turning localised issues of some tea estates run by the Plantation Companies into a perceived crisis for the entire “Ceylon Tea” brand.

What is most disappointing is that her visit to the tea fields in the PCs and the interviews she conducts amount to little more than superficial storytelling, failing to substantiate the innuendo she uses to cast doubt on the Sri Lankan tea industry. By the end of the documentary, there is no clear answer to the very question she set out to investigate. Yet, between the introduction and the conclusion, the report creates uncertainty about the credibility of “Ceylon Tea” in terms of ethical compliance—without providing the necessary depth or evidence to support such claims.

One sided narrative

In her piece to the camera on some unknown estate she says, “this is not an easy place to work as you can see, these are difficult fields to navigate.” She implies that the overgrown tea bushes is a hindrance towards meeting the required daily targets by tea pluckers. She also has concerns about leeches and snakes in the area. However, instead of probing further into the actual reasons why workers struggle to meet their targets, the reporter misses an opportunity to ask the right questions. A more thorough investigation would have revealed that leaf yield varies by region and season. Furthermore, the mention of snakes as a significant workplace hazard is misleading—had she consulted local hospitals, she could have easily obtained data on snakebite incidents in the area.

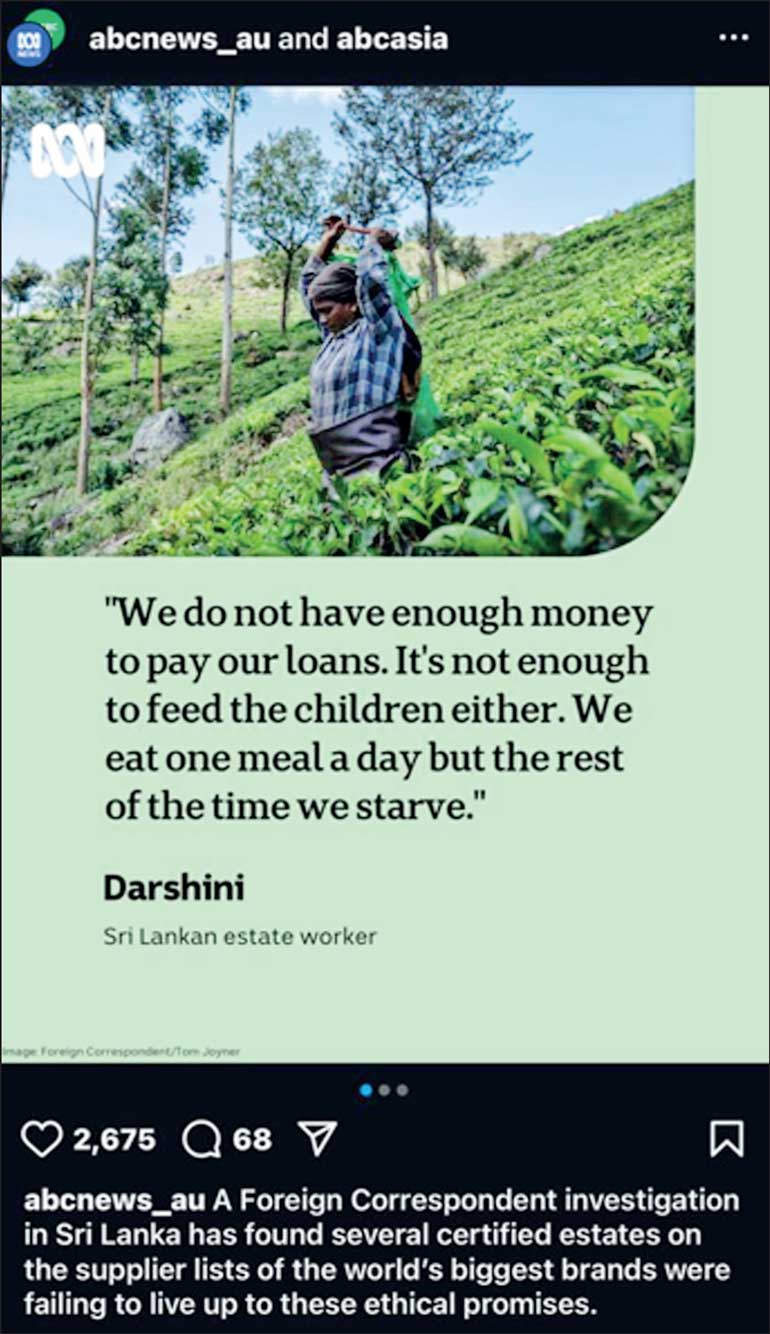

She also criticises the certification process, highlighting the lack of toilets and drinking water in the fields. The documentary claims that supervisors prevent workers from speaking to auditors, but when Selvaratnam asks one of the women what she would tell an auditor if she had the opportunity the response is vague: “I’ll tell them a bit about our struggles. After all we are ladies, are we not—we have to clear out the weeds, we have to pluck a lot of tea, we have to carry it from up there, all the way down, and when we carry it down we get back pain and headaches.” While these are certainly difficult working conditions, they do not automatically equate to labour violations or systemic abuse. This could simply be the experience of one individual or a reflection of the physical demands of agricultural work in general. The correspondent, Naomi Selvaratnam, acknowledges that if the workers pick enough, they are paid the minimum wage guaranteed under the (international) certification but claims that many, like the one tea plucker she interviews, cannot survive on that wage and remain caught in a cycle of pay advances, meaning she is constantly in debt. She interviews a woman named Dharshini, who says, “We don’t have enough money to pay off our loans, or enough to feed the children. We eat one meal a day but the rest of the time we starve. When there’s no food, we feel sad. Yesterday my children went to school without any food and I went to the field without any food. Our income isn’t much so we can only pay back a little at a time.” Darshini says she’s raising three children on her income alone, struggling to make ends meet. This is undoubtedly a harsh reality for many estate workers. However, tea industry specialists have pointed out that broader social factors contribute to these struggles. Notably, in the ABC documentary, there is no mention of the men in the family, and the absence of interviews with them leaves a crucial gap in the story. If the reporter had investigated further, she would have found another angle—one that could have provided a more comprehensive explanation for the challenges these families face.

ABC had the opportunity to deliver a nuanced and insightful report. Instead, it presented a one-sided narrative that barely scratches the surface of the real issues.

Child labour

Naomi Selvaratnam interviewed a 12-year-old child working in a privately owned vegetable garden on a PC tea estate. The child, who had dropped out of school a year earlier, told her: “I went to work because my family was suffering. If I come to work, I get paid 500 rupees, and that helps us buy food. I really want to go to school, but when I get home from work at 5 o’clock, I can’t even play. Often, there isn’t food at home. When there isn’t any work, we go hungry and just drink a cup of tea.”

This interview was arguably the most striking moment of the 28-minute program, offering a glimpse of the poverty on Sri Lanka’s tea estates. However, when analysing ABC’s journalistic approach, a critical question arises first: how was this interview obtained?

At the beginning of the program, the correspondent categorically states that they have taken measures to protect the identities of their interviewees by not mentioning the names of the estates, implying that individuals interviewed are at risk. According to UNICEF’s ethical guidelines on interviewing children, the best interests of the child must take precedence over any other consideration, including advocacy for child rights. Most importantly, permission for such interviews must be obtained from both the child and their guardian, in writing, and under circumstances that ensure they are not coerced or unaware of the potential consequences of participating in a widely disseminated story. Furthermore, steps must be taken to ensure that the child’s home, community, or identity is not revealed in a way that could endanger them.

This leads to a critical question. Why wasn’t the child’s face blurred out in the visual?

And also another one: If the child’s parent or guardian was present during the interview—as ethical journalism mandates—why were they not asked about their child working instead of attending school? If they were indeed present, it is likely the answer would have been the same one as the child gave, that financial hardship forced them into work. However, including the parent’s perspective would have made it clear that the responsibility for the child’s well-being primarily lies with their family. And proved objective journalism!

Poverty

The broader issue of poverty, which drives children to work in private gardens for rupees 500 a day, is undeniably a serious concern that demands attention. But for ABC’s reporting to be truly impactful, it needed to go beyond a single anecdote. Was child labour a widespread problem on these estates? Had the authorities taken note of such cases? (The authorities in this case would be state agencies. As Naomi Selvaratnam clearly says in her documentary that the plantation companies are on government land). Was there any available data on the extent of the issue? Answering these questions would have given viewers a clearer and more comprehensive understanding of the gravity of the situation.

Instead, by presenting just one isolated case without context, the report risks exaggerating the problem rather than providing a well-rounded analysis.

In her interview with Planters’ Association of Ceylon Spokesperson, Roshan Rajadurai, ABC correspondent Naomi Selvaratnam says, “Can I ask a few questions just relating to your estates? We visited one of them which falls under your company and we found that there were children that were under the age of 16 who weren’t attending school and were working in the tea estate’s private gardens.”

Rajadurai’s response to this issue is clear—if they were working in a private vegetable garden, the responsibility lay with the parent, not the plantation company. However, the ABC correspondent uses the word children instead of a child. Which was it? Did she actually find multiple children working in vegetable gardens, and if so, why wasn’t this properly documented in her report? If it was only one child, then using the plural is misleading. More importantly, this is an example of clumsy journalism. She had the opportunity to investigate the extent of the issue, gather concrete data, and question the spokesperson of the Planters’ Association with factual evidence. Instead, this segment of the report relies on innuendo and hearsay—clearly a let down on objective journalistic standards.

Housing

Commenting on the housing available for tea plantation workers and families, the ABC reporter has this to say in the documentary “The tea pluckers don’t just work on these estates, they live here in supplied dwellings known as line houses. Under certification standards, they have to be provided with safe, clean, and decent homes.” The report goes on to show some damaged houses and interviews from people who live there and complain about their living conditions. But did ABC actually do their homework before pointing fingers? Did they miss out some vital facts?

In Sri Lanka, all Regional Plantation Companies operate on government-owned leased land, so it is the government’s responsibility to build and maintain adequate housing for workers. Tea companies contribute to a common fund managed by the Plantation Human Development Trust (PHDT), a tripartite organisation made up of the Government of Sri Lanka, the Planters Association, and the Trade Union. Because the Certificate Holder does not own the land, auditors are unable to evaluate housing during audits, which means that Rainforest Alliance’s housing standards do not apply to these companies.

This is a factor that has been confirmed through multiple sources within the industry.

It has also been confirmed that private vegetable plots are not included in the certification. Tea estate management does not oversee these small private gardens, which are typically home gardens or government-allocated plots used by workers or other individuals to supplement their income. Because these gardens are privately owned and separate from the estate, they fall outside the scope of international certifying agencies, and auditors do not have access to them.

Roshan Rajadurai, spokesman for the Planters’ Association of Ceylon, confirmed that the sale offer in 1992 for the privatisation of the Regional Plantation Companies (RPC) document stipulates the mandatory release of line rooms and cottages occupied by estate workers, along with the vegetable gardens cultivated by these workers from the responsibility of the management from the RPCs and came under the purview of the state.

Rajadurai also says that in 1992, a separate ministry known as the Ministry of Estate Housing and Infrastructure Development was established under a Cabinet Minister representing the plantation community. This ministry is tasked with providing housing, health care, sanitation, water supply, and other amenities for plantation communities, as outlined in a Government Gazette. As a result, the estate management companies were relieved of any responsibility or liability in these areas. Rajadurai expressed his surprise that, despite clarifying this information to the ABC reporter, she continued to assign these responsibilities to the regional plantation company.

Verisimilitude

Selective use of sources, expert commentators, and interview excerpts can create the illusion of consensus, even on debated issues. This technique aligns with verisimilitude—the appearance of truth—allowing news outlets to shape narratives through selective storytelling, visual framing, and expert curation rather than objective reporting. By emphasising specific incidents, journalists can make a story feel authentic while distorting the broader reality. Selvaratnam telling the viewers that this is an isolated tea estate, gives the impression that there was something to hide in that location which needed to be revealed. “Estates like these are so remote that no one comes here unless they have a reason and that’s why it remains hidden.”

So what was the intention of this statement?

Moreover, sensationalism relies on verisimilitude by crafting compelling yet distorted portrayals of a situation. A well-edited documentary with dramatic music, emotionally charged interviews, and carefully chosen expert opinions reinforces the perception of truth, making viewers less likely to question its authenticity.

This reinforces the importance of media literacy. Viewers must critically assess the information they consume, recognising the potential for bias, selective storytelling, and sensationalism. Cross-referencing multiple sources, seeking out independent journalism, and questioning the framing of stories are all essential practices in an era where narratives can shape public perception more powerfully than ever before.

While journalism remains a vital tool for democracy and accountability, the techniques used to craft compelling television narratives must be scrutinised. Only by recognising these trends can audiences navigate the complex landscape of modern media and separate fact from fiction.

Selective reporting

The ABC documentary was explicitly framed as an inquiry into whether Sri Lankan tea production as a whole is ethical. However, a crucial factor in the analysis is that over 75% of Sri Lanka’s tea production comes from private owners—small and medium-sized farmers—while plantation companies (PCs) account for only about 23%. So why did Selvaratnam go in the direction of the PCs only, why not the small holders? Was the ABC correspondent aware of the fact that she was looking only at the smaller component of the larger brand of “Ceylon Tea”? If not, it reflects poor research. But if she deliberately ignored this matter, then there is a serious flaw in the reporting —one that relies on selective reporting to misrepresent, potentially harming the larger plantation companies and thousands of small-scale tea growers not only in the highlands of Sri Lanka but across the island, who are an integrated part of the single source brand “Ceylon Tea,” to markets like Australia!

Problems on the estate

This writer acknowledges that there are ongoing challenges between plantation companies and the estate workforce—issues that have persisted for decades. An amicable and lasting solution is essential for this community, which has long been denied not only their rights but also full acceptance into mainstream Sri Lankan society.

Resolving these challenges is crucial, not just for the workers’ well-being but also for the sustainability of the businesses that depend on them. The plantation industry, which has thrived for close on two centuries on the labour of these workers, must evolve in a way that ensures both economic viability and fair treatment.

This issue requires the active involvement of all stakeholders, fostering dialogue rather than division. Most importantly, any efforts to address these disputes must not sever the vital connections between plantation management and their workers. Finding solutions will require honest brokers—mediators committed to ensuring fair outcomes for all involved. Ultimately, what is needed is a path forward that delivers win-win solutions for both the workforce and the industry.

To truly understand Sri Lanka’s tea industry, one must recognise its complexity. Numerous factors influence the final price of a cup of tea, both locally and internationally, and this price, in turn, affects the entire supply chain. More importantly, the question of who determines the price is a critical issue that requires deeper investigation.

Simply swooping in with cameras onto tea estates in search of a quick scoop will never reveal the full picture or the right answers.

Intentions

Even the best intentions can lead to unintended consequences if not handled carefully. The ABC report on Sri Lanka’s tea, regardless of its intent, should have been approached with greater diligence. In today’s world, investigative journalism must be driven by data and deeper analysis—it cannot rely on anecdotal evidence alone.

As a writer, I still believe mainstream journalism remains the most reliable source of factual reporting. While social media has its place, mainstream media is the foundation. Journalists and editors must take this responsibility seriously—it is the very lifeblood of their profession. If public trust is lost, so is everything journalism stands for.

Ultimately, a journalist must go beyond merely assembling facts and hoping they form a compelling story. A respected and reliable journalist—one trusted by both peers and the public—is someone who seeks the truth, no matter how uncomfortable it may be. While exposés have their place, they often reveal only part of the picture. ABC must continue investigating this story with sharper insight and deeper understanding. Their reporting should be fair, balanced, and accurate, benefiting not only the Sri Lankan tea industry but also buyers and, ultimately, consumers in Australia.

(The writer is a communications professional with 44 years of experience. He has worked as a correspondent on the frontlines during the war years in Sri Lanka and has been a reporter on the news and investigation desks of several English newspapers. He has also been a Business Editor and Deputy Editor of two national newspapers with work experience with international news teams from CNN, German Television (ARD), and Deutsche Welle (DW) in Sri Lanka. Devotta was also the News Director for a leading private media organisation for eight years, managing a trilingual newsroom that delivered news to three television channels and four radio stations. Fluent in English, Sinhala, and Tamil, he is currently a columnist for Daily FT and a Public Affairs consultant.)