Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 18 July 2020 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The political party structures and constitutions, and the inflexible workings within the legislature are indeed indicative of parliamentary autocracy

The separation of powers within a state, reflects the nature of governance of a state. Under this model, a state’s government is divided into branches with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that powers of each branch are not in conflict with the other.

The separation of powers within a state, reflects the nature of governance of a state. Under this model, a state’s government is divided into branches with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that powers of each branch are not in conflict with the other.

The typical division is into three branches; the legislative, executive and judiciary – the ‘trias politica’ model. This model can be contrasted with the fusion of powers in parliamentary and semi-presidential systems, where the executive and legislative branches overlap.

A brief look at history in the Western world

The idea that a just and fair government must divide power between various branches has deep philosophical and historical roots. In his analysis of the government of Ancient Rome, the Greek statesman and historian Polybius identified it as a ‘mixed’ regime, with three branches: monarchy (the consul, or chief magistrate), aristocracy (the Senate) and democracy (the people).

These concepts greatly influenced later ideas about the separation of powers being crucial to a well-functioning government. Centuries later, the Enlightenment philosopher Baron de Montesquieu wrote of despotism as the primary threat in any government. In his famous work ‘The Spirit of the Laws’, Montesquieu argued that the best way to prevent this was through a separation of powers, in which different bodies of government exercised legislative, executive and judicial power, with all these bodies subject to the rule of law.

The separation of powers, therefore, refers to the division of responsibilities into distinct branches of government, by limiting any one branch from exercising the core functions of another. The intent of the separation of powers is to prevent the concentration of power, by providing for checks and balances.

The principle of ‘checks and balances’ is that each branch is bestowed the power to limit or check the other two – which creates a balance between the three separate branches of the state. This principle induces that each branch is to prevent either one of the other branches from becoming supreme, thereby securing political liberty.

Immanuel Kant was an advocate of this, noting that “the problem of setting up a state can be solved even by a nation of devils”, as long as they possess an appropriate constitution to pit opposing factions against each other.

Checks and balances are designed to maintain the system of the separation of powers, keeping each branch in its place. The idea is that it is not enough to separate the powers and guarantee their independence, but the branches need to have the constitutional means to defend their own legitimate powers from the encroachments of the other branches.

They guarantee that the branches have the same level of power (co-equal), so that they can limit each other, avoiding the abuse of power. The origin of checks and balances, like separation of powers itself, is specifically credited to Montesquieu from the Enlightenment era, with his book; ‘The Spirit of the Laws’, published in 1748. It is Montesquieu’s principle of the separation of powers that was implemented in the 1787 Constitution of the United States.

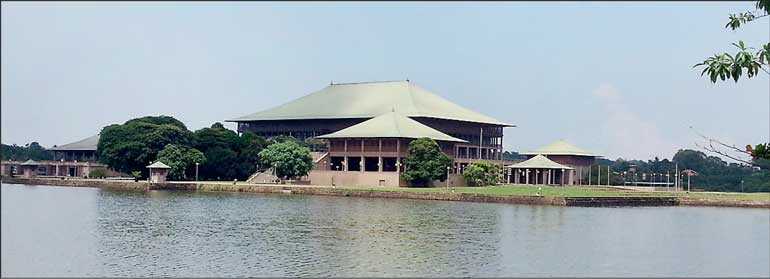

Contemporary Sri Lanka

It can be said that independent Ceylon and the then Sri Lanka since 1972, has been following a trias politica model. However, many would challenge the degree of independence each arm of the country’s governance structure has had since 1972. It is also a discussion point whether the checks and balances in place have been sufficiently effective, to ensure this independence and to guarantee the separation of powers.

The Legislature

Ceylon as a nation was known as such till 1972, functioned under the Soulbury Constitution from Independence in 1948 until 1972, when a new constitution replaced it. In 1970 Sirimavo Bandaranaike swept to power in coalition with the Marxist parties, LSSP and the Communist party. This was probably the first time a political party or a combination had a two-thirds majority. This two-thirds majority of seats however was secured with less than 50% of the polled vote (49%). The two-thirds majority enabled her to introduce the first Republican constitution in 1972.

The second occasion was when J.R. Jayewardene gained a five-sixth majority in 1977. He secured this huge Parliamentary majority with just over 50% of the polled vote (50.92%). He introduced the Executive Presidential model in 1978. Until then, the country’s parliamentary system was based on members being elected on first past the post system.

The 1978 constitution introduced a proportional representation model effective from the following parliamentary election. The 1978 constitution has since been amended on 19 occasions.

The political parties in government voted without any dissention from within, on each occasion the constitutions were introduced. This was in line with strict party constitutions that did not afford much flexibility among the members to express dissenting views within the party or any flexibility to express dissenting views in Parliament.

While some public consultative processes were undertaken on both occasions, it is debateable whether they were effective and whether they had any grassroots consultations. The introduction of the new constitutions in this manner, questions the validity of the independence of the legislature and whether they had the people’s will for the new constitutions.

The principle of ‘checks and balances’ is that each branch is bestowed the power to limit or check the other two – which creates a balance between the three separate branches of the state. This principle induces that each branch is to prevent either one of the other branches from becoming supreme, thereby securing political liberty

On one hand, the enactment of constitutions by a government with less than 50% (49%) of the popular vote cast, and on another occasion, with just over 50% of the vote (50.92%), questions the moral validity of the constitutions from a democracy context.

On the other hand, the absence of flexibility available for members of Parliament to consult with their constituencies and express dissention, if that was the view of their constituents, questions the independence of legislators and the objectivity of democracy.

Besides constitution making, amendments to constitutions have faced the same fate. The party constitutions too are hardly democratic as they are framed and amended in such a manner as to ensure the survival of a leader through mechanisms that cannot be termed democratic.

Party members are hardly ever consulted or given power to overturn a leader’s decisions if they feel such decisions are not in the best interest of the country. Such mechanisms give inordinate powers to the leader and encourages the expansion of Yes men and women, favourites over talent, ability and liberal thinking.

In this context, the independence of the legislature is questionable and so is adherence to the Lincolnian “government by the people, for the people” visionary objective. The political party structures and constitutions, and the inflexible workings within the legislature are indeed indicative of Parliamentary autocracy.

The Executive

The powers granted to the Executive Presidency in the 1978 constitution questions the independence of the legislature. This is aggravated by the questions on independence of the legislature as mentioned earlier.

For all intents and purposes, the 1978 constitution appeared to make the legislature an institution that is rubber stamped at the Presidents bidding. The 19th Amendment to the 1978 constitution reduced the powers of the Executive Presidency by transferring them to the legislature, thus enhancing the separation of powers.

However, flaws in the 19th Amendment seems to have impacted the roles and responsibilities of the Presidency; causing confusion between its role and that of the legislature, and that of the Prime Minister within the government that was elected in 2015.

This was aggravated by the fact that the President and the Prime Minister were from two different major political parties. The government elected in 2015 was one of the most dysfunctional governments that the country had since independence. It is clear that the 19th Amendment needs revising, and while retaining some of its very significant positive features like the independent commissions – it should coherently define and demarcate the roles and responsibilities of the President, the legislature and the Prime Minister.

The Judiciary

The judiciary in Ceylon and Sri Lanka has always functioned independent to the executive and the legislature, quite relatively. There have been occasions when the juggernaut powers of the Executive Presidency had compromised the independence of the judiciary.

The International Crisis Group in a report published on 30 June 2009 (https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/sri-lanka/sri-lanka-s-judiciary-politicised-courts-compromised-rights) stated that at independence in 1948, Sri Lanka had a comparatively professional and independent judiciary.

The new constitutions in 1972 and 1978, however, cut back on the judiciary’s protection from parliamentary and presidential intrusions. The 1978, the constitution vested unfettered control of judicial appointments in presidential hands.

Unlike other South Asian countries, no strong tradition or norm of consultation between the president and the chief justices developed. Nor did predictable rules immune from manipulation, such as promotion by seniority, emerge.

Continuing, it states that the 17th Amendment, enacted in October 2001, attempted to depoliticise a range of public institutions, including the judiciary, by establishing a constitutional council. The council limited the power of the president to make direct appointments to the courts and independent commissions.

In an article titled ‘Independent Judiciary and Rule of Law: Demolished in Sri Lanka’ by Rohini Hensman in the Economic and Political Weekly in March 2013, a critical and worrying analysis of the function and independence of the judiciary was made.

Since one of the key impetuses of the General Election scheduled for 5 August is the need to introduce a new constitution, it is worthwhile that all political parties and citizens ponder the fundamental premise that underpins democratic governance: whether the three branches, the legislative, the executive, and the judiciary, or the trias politica model, has enshrined the separation of powers, and whether they are practiced in effect. If the country is to move forward on the democratic governance path, it should recognise where it has failed to practice this separation of powers, and incorporate the necessary ‘checks and balances’ to ensure they are practiced

Sarath Wijesinghe, a President’s Counsel, former BASL Secretary and former Ambassador to UAE and Israel writing in the Daily FT on 31 January 2019 stated: “Independence of the judiciary is the barometer of the computation of the democracy, and culture of a nation expecting justice and fair play for the resolution of their disputes from impartial and politically insulated independent judges appointed under the constitution.”

“It is a good sign that in Sri Lanka the Judiciary today is well-paid, remunerated, protected and looked after, respected, and has gained the confidence of the citizen, maintaining impartiality and trust of the litigants.” (Independence of the judiciary worldwide http://www.ft.lk/columns/Independence-of-the-judiciary-worldwide/4-671988).

However, he also states that it is very difficult to answer whether justice has been dispensed by an independent judiciary and it is only the average citizen/litigant who may be capable of answering this million-dollar question.

He goes on to say: “In the West and many others in the Commonwealth and civil law jurisdictions, the judiciary is independent with sufficient checks and balances. But in highly-politicised societies with rampant bribery and corruption, mostly in less-developed countries, this has ripple effects all over the society as a cancer, lowering standards in the lowest ebb; it is not a breeding ground to maintain such standards.”

He contends as most would that judges should be free to make decisions because they are charged with the ultimate decision over life, properties, rights and duties of the citizen, including all kinds of freedoms enshrined in the Constitution and by way of conventions, powers and traditions vested within the executive with great trust: to be impartial, and should not be undermined overlooked or destroyed.

They are the guardians of the supreme law and the citizen. However, he expresses a feeling that many probably share that it is “unfortunate that successive governments and the leaders of the Executive have misused and violated this sacred responsibility entrusted to them as the guardians and temporary trustees of the ‘Temple of Justice’, which is the backbone of the freedom and equality”.

The jury seems to be out and still deliberating whether the judiciary in Sri Lanka is as independent as it should be and whether incursions have been made especially by the Executive to erode that independence.

Since one of the key impetuses of the General Election scheduled for 5 August is the need to introduce a new constitution, it is worthwhile that all political parties and citizens ponder the fundamental premise that underpins democratic governance: whether the three branches, the legislative, the executive, and the judiciary, or the trias politica model, has enshrined the separation of powers, and whether they are practiced in effect.

If the country is to move forward on the democratic governance path, it should recognise where it has failed to practice this separation of powers, and incorporate the necessary ‘checks and balances’ to ensure they are practiced.