Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Thursday, 21 September 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Internet of Things, or IoT, is the next technological revolutionpoised to change the way we, and everything around us, communicate and interact. Management consultant company McKinsey forecasts that IoT will generate up to $11trillion a year in economic value by 2025, 15% of the current global GDP.This translates into substantial growth potential;global information companyIHS forecasts a 17% CAGR in connected devices to 75b globally from 2015-2025.

But how much of this potential is relevant to Sri Lanka?In Sri Lanka, significant investment in IoT infrastructure is required to support long-term growth in IoT. However, in the short term, the country has the ability to kick-start innovation by developing simple and customised IoT solutions for key economic sectors.

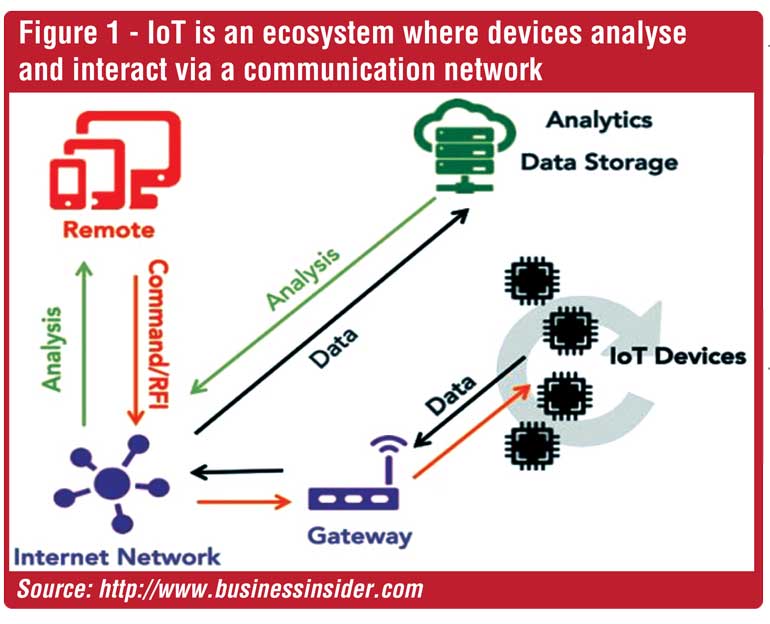

IoT can be described simply as an ecosystem where a multitude of devices communicate over a network such as Wi-Fi, in orderto jointly optimise their respective tasks (Figure 1).Data collected by these sensors is stored and analysed aggregately, to enable the system to make decisions. For example, the Nest smart thermostat canadjust the temperature inside your home based onyour daily routine. The device communicates with a multitude of sensors, including your vehicle to gauge its location, and analyses the information to holistically optimise energy efficiency.

The challenge: Sri Lanka requires significant investment in IoT infrastructure

The key contributor to the IoT value chain is the platform (accounting for 30-40% of value), which requires well-established IoT network infrastructure. On the face of it, Sri Lanka currently has reasonable 3G/4G coverage of 78% compared to 91% in the US and 94% in Singapore and over 100% mobile phone penetration. However, development of large-scale IoT solutions requires investment in specific infrastructure, which is fraught with challenges.

First, IoT networks are heterogeneous and vary significantly in terms of cost, configuration, and data throughput. As such, different, application-specific network technology must be used; for example, wearables are suited to use Bluetooth Low-Energy (BLE) networks to transmit data over a few meters, Low-Power Wide-Area (LPWA) networks support low data throughput coverage over five km for smart city applications, and high-power Neighbourhood Area Networks (NANs) are suited for transmissionover 10km for smart grid applications.

Second, imported IoT solutions will likely have to conform to regulatory standards that vary according to country (e.g., different frequency bands and maximum allowed power emissions), which can lead to significant complications during adoption. In this sense, local home-grown solutions may have a potential edge.

Furthermore, all these technologies must be standardised within each of their ecosystems to allow for seamless interoperability.Thesechallenges are further exacerbated by the lack of commitment from enterprises to invest in IoT infrastructure, which results in 60% of IoT projects stalling at the proof-of-concept stage, according to worldwide leader in IT and networking Cisco.

Understanding these bottlenecks, regional peers are investing heavily in IoT infrastructure. In Thailand, SK Telecom and CAT Telecom have deployed an IoT-specific LPWA network in central Bangkok and Phuket. Such initiatives are expected to drive growth of 17x in the country’s IoT spending over 2014-2020, according tomarket-research companyFrost and Sullivan. Similarly, in Malaysia, Atilze Digital and edotco Group havedeployed an LPWA network in the Klang Valley region.

Clearly, if Sri Lanka is to progress towards large-scale IoTadoption in the long term, significant investment in infrastructure is required. However, with its current infrastructure’s limited capabilities, it makes more sense for Sri Lanka to focus on simpler, more confined IoT systems.

Short-term opportunity: Sri Lanka should focus

on simple IoT projects, targetedat core economic sectors

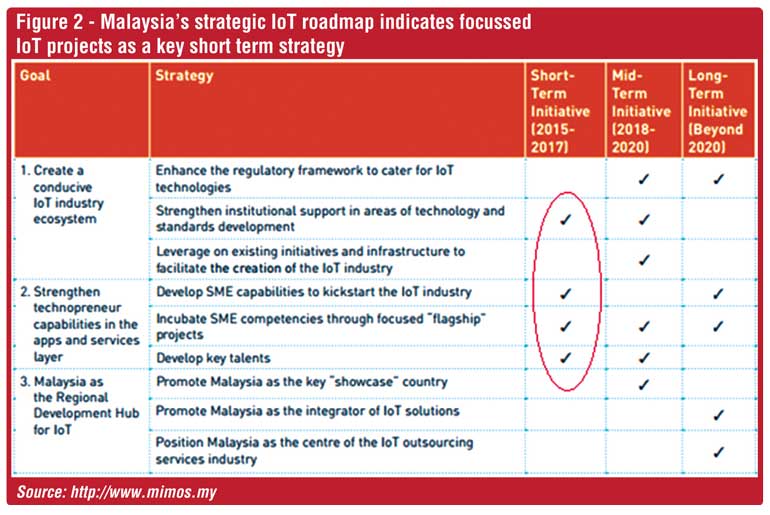

While investing in the required infrastructure, regional peers have drawn up strategic IoT roadmaps to overcomeshort-term hurdles.A good example is Malaysia, which has segmented its IoT strategy via a timeline to allow the effectiveset-up of an environment while it invests in the required infrastructure. Some of its primary short-term goals are initiating focused pilot projects and developing the talent pool (Figure 2).Focussed pilot projects are effective catalyststhat helporganisationsunderstand and overcome application specific IoT challenges.

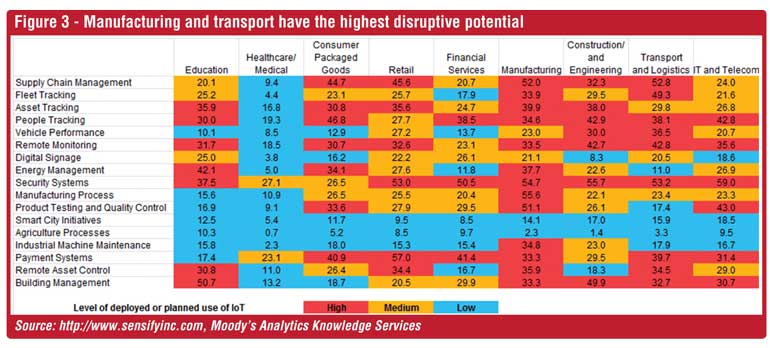

In addition to adopting a similar framework, Sri Lanka should also seek to maximise the value added from IoT to GDP by considering (1) sectors with the highest disruptive potential from IoT and (2) sectors that make substantial contributions to GDP. A survey conducted by global market intelligence firm IDC shows that the manufacturing and transport and logistics sectors are among those that have the highest disruptive potential from IoT (Figure 3; the numbers display the impact ranking out of 100).

In this context, Thailandexpects the largest investment in IoT to be in manufacturing operations ($ 1.3b) until 2020, followed by freight monitoring (USD0.5bn).Considering that both the manufacturing (15.0% of Sri Lanka’s 2015 GDP) and transportation and logistics (10.8%)sectors are key contributors to the local economy, this presentsan IoT opportunity profile very similar to that ofThailand.

Currently, Sri Lanka has a few examples of simple, successful IoT projects of its own. In the utilities sector, JLanka Technologies’“Smart Meter” monitors and reports granular utility usage data so that the state-run Ceylon Electricity Board can reduce peak power generation by shifting the load of devices (such as washing machines) that do not require a specific time for operation.

Similarly, in the agricultural sector (7.9% of Sri Lanka’s 2015 GDP), sensors are used to control nutrients and PH levels, and treat fungi in soil, driving increased yield. We therefore believe Sri Lanka should be able to create similar, value-adding IoT solutions for thesectorswith high disruptive potential.

To illustrate the concept, we examinein more detail belowexamples of how peers have successfully implemented IoTsolutions to deal with specific issues.Sri Lanka may not be able to replicate such solutions to the same extent, but it should be able to adopt a basic solution that operates within the strict confines of a particular industry’s processes.

Manufacturing: Using IoT to increase productivity

Manufacturing is set to account for a largec.32% of total IoT spending in the Asia-Pacific region by 2020. Our closest peers – the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia – plan to increase manufacturing IoT spendingby 5-10x over 2014-2020. The technology should result in significant productivity gains via automation of basic processes and in reducing manufacturing costs via processes such as predictive maintenance.

Predictive maintenance using IoT is estimated to reduce maintenance costs by 10-40% and reduce downtime by 50% in factories, according to McKinsey. For example, this technology drove $ 9m in cost savings at Intel’s semiconductor fabrication plant in Penang, Malaysia, by actively utilising embedded sensors to recognise faulty equipment and increase their uptime.

Transport and logistics: IoT in fleet management and smart traffic to reduce delays and costs

This sector has considerable disruptive potential due to the large opportunity it presents for IoT to revolutionise fleet management and smart traffic.Currently, Sri Lanka’s major logistics players do have reasonably intricate fleet management solutions, but as management in key logistics corporates have clarified,most systems still rely heavily on their human counterpartsand have limited machine-to-machine connectivity.Therefore, IoT offers a large opportunity here as well.

For example, a connected fleet utilising predictive asset lifecycle management can help autonomously decide when it requires maintenance. In 2012, a project carried out by Volvo and DHL using the technology was found to increase vehicle uptime by over 30%.Advantages of IoT extend further to traffic management.

In Malaysia, Cyberviewrecently developed LTE-equipped controllers to be mounted on traffic lights; these run video cameras with analytical capabilities, enabling them to intelligently direct traffic in the Persiaran Multimedia, Cyberjaya region. The sensors wirelessly transmit the data via the “cloud” to the central Traffic Management Command Center that has direct access to the traffic-light controllers.

The system achieved a significant 65% decline in waiting time during peak hours. Such initiatives are expected to increase Malaysia’sspending on IoT transport by 5-10x to c.USD70mor to more than 8% of the country’s total IoT spendingby 2020, according to market-research company Frost and Sullivan.

Long-term recommendation: Investin IoT infrastructure and promote industry-wide integration

Beyond the five-year horizon, the incremental value added by adopting confined IoT projects diminishes rapidly. Only when the communication infrastructure is fully in place can Sri Lanka leverage it to drive adoption of full cross-ecosystemoptimised IoT systems, and hence economic value addition, similar to that envisioned in the mid-term strategy of Malaysia’sroadmap (Figure 2).

Currently, supportive technology solutions are being explored locally, including LPWAnetworks on Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6), fibre optics, and communication via 4G LTE, but these are mostly experimental or are used in a few remote cases in very confined applications. A few niche private enterprises are actively implementing IoT solutions locally;for example, Senzmate concentrates on creating IoT solutions focused on enterprise, logistics, and agriculture.

It is essential that the Government actively promote the integration of such entities and their services with larger corporates and SMEs to maximise the adoption of IoT.This also implicitly means establishing a regulatory framework for technology adoption, IP protection,product standardisation, and actively investing in enhancing the IoT talent pool.

In conclusion,we believe Sri Lanka can benefit from the adoption of simple IoT solutions capable of running on its current infrastructure in the short term, especially if it identifies and applies these solutions to areas with the most disruptive potential. However, in the long term, significant investment in IoT infrastructure would be needed for the country to continue to extracteconomic value.

(GamikaSeneviratne is a Senior Associate Vice President, Investment Research at Moody’s Analytics Knowledge Services Colombo.He holds a First-Class Master’s degree in Electrical and Electronic Engineering from Imperial College London. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of his employer, Moody’s Analytics Knowledge Services.)