Wednesday Mar 04, 2026

Wednesday Mar 04, 2026

Monday, 8 October 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A dynamic analysis of Sri Lanka’s growth performance

My former colleague at the Central Bank and presently Senior Economic Advisor to UNDP, Dr. Amarakoon Bandara, delivering a public lecture at the Bank on Growth Dynamics, has  opined that Sri Lanka can still open its window of opportunities if proper policies are adopted, despite its dismal economic performance since independence (available at: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/node/2224 ). Growth dynamics refers to the area of economics that helps policy makers to understand how an economy has progressed over time – its achievements, failures, constraints and prospects. This is different from the typical static economic analysis in which an analyst will stop the clock and compare the situation in the economy between two time periods, known as comparative statics. It is not often an economy is viewed from a dynamic perspective and Bandara’s attempt was a rare instance.

opined that Sri Lanka can still open its window of opportunities if proper policies are adopted, despite its dismal economic performance since independence (available at: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/node/2224 ). Growth dynamics refers to the area of economics that helps policy makers to understand how an economy has progressed over time – its achievements, failures, constraints and prospects. This is different from the typical static economic analysis in which an analyst will stop the clock and compare the situation in the economy between two time periods, known as comparative statics. It is not often an economy is viewed from a dynamic perspective and Bandara’s attempt was a rare instance.

A risk-reward game involving three players

Bandara commenced his lecture by presenting to his audience a hypothetical ‘risk-reward game’ involving three players. The three players had begun their game with more or less a  similar resource endowment and, therefore, neither one was above or below another. The first player had 400, the second 150 and the third, 140 and this could have been anything from rice to rupees to dollars. They were supposed to play the game to reach three levels of rewards, again in the same respective measuring stick, say 53000, 27000 and 4000. This set of final rewards offer them a very high to very low return from where they had started. It was up to them to adopt the most effective and efficient strategy to grab the highest reward possible.

similar resource endowment and, therefore, neither one was above or below another. The first player had 400, the second 150 and the third, 140 and this could have been anything from rice to rupees to dollars. They were supposed to play the game to reach three levels of rewards, again in the same respective measuring stick, say 53000, 27000 and 4000. This set of final rewards offer them a very high to very low return from where they had started. It was up to them to adopt the most effective and efficient strategy to grab the highest reward possible.

Singapore and Korea bagging the rewards

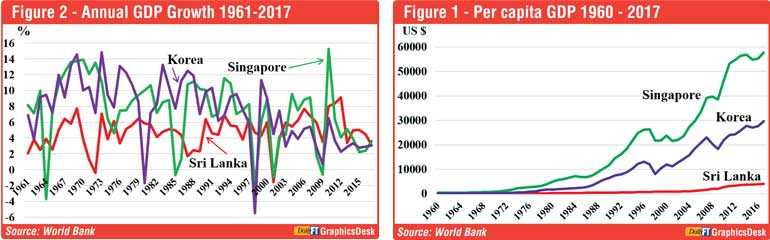

Ironically, the three players were Singapore, Sri Lanka and South Korea in 1960, in that order. The time span for the game was extended to 2015 but it could have been any other year earlier or later. Though they had begun with a similar endowment, Singapore emerged as the winner with the highest reward, Korea in the second place though less than Singapore but much more than Sri Lanka and Sri Lanka, the lowest and the laggard in the game. This is shown in figure 1. Bandara, then, has dug out the dynamic forces that had contributed to this excessively unequal outcome of rewards. There  have been a number of socio-politico-economic factors that have helped both Singapore and Korea to bag the high reward and caused Sri Lanka to fail in its attempt to do so.

have been a number of socio-politico-economic factors that have helped both Singapore and Korea to bag the high reward and caused Sri Lanka to fail in its attempt to do so.

Economic ups and downs have to be corrected quickly

The annual real economic growth rates attained by these three players during 1960 to 2015, said Bandara, demonstrated that they all had experienced ups and downs in growth as shown in figure 2. However, the difference had been that both Singapore and Korea had been able to very quickly recover from the downs and place the respective economies back on the long term economic growth path, whereas Sri Lanka had failed to do so. Consequently, the attainment of Sri Lanka had not only been prolonged downs but also been lower by 4 to 5% than the other two players. As a result, though the initial endowment was the same, the end result had presented a massive gap in the final rewards. Thus, Sri Lanka could only savour in the past glory and not in any present day achievement.

Sri Lanka taking one step forward and two steps backward

Bandara had observed that in the case of Sri Lanka, both the political and economic growth cycles had coincided with each other. Whenever a pro-free market economy ushering political party had been in power, there had been a slight upward movement in economic performance. When the power had been shifted to the opposite camp, which had invariably happened almost alternatively, the initial gain had been reversed. Thus, according to Bandara, Sri Lanka had been in the habit of taking one step forward and taking two steps backward all throughout the period under consideration. This policy inconsistency and reversal had not been noticed in the case of both Singapore and Korea. As a result, both of them had been able to follow the same policy package by taking forward steps continuously. Any backward step had been only when they had been hit by some unavoidable external shocks like the East Asian financial crisis in 1997-8 or global economic downturn in early 2000s.

Promotion of savings through positive real interest rates

Another stark difference in policy had been the use of monetary policy to promote savings for investment in these three countries. For any economy to grow, it has to invest a sizable proportion of its annual income to replace the worn-out capital on the one hand and expand the production capacity on the other. Those investments have to be funded either through savings generated by citizens by consuming a lesser amount out of incomes or by attracting savings made by foreigners by consuming less than their incomes or by resorting to both. A crucial requirement for promoting domestic savings has been, among others, the need for maintaining market interest rates sufficiently higher than the prevailing inflation rate – a situation known as having a positive real interest rate regime. Bandara had noted that in 1960 in both Singapore and Korea real interest rates had been negative but they were converted to positive soon after through a conscious monetary policy involving an increase in the market interest rates above the inflation rate. It delivered a miracle by increasing domestic savings which were in turn reinvested in the economy.

Sri Lanka’s anti-savings interest rate policy

But Sri Lanka had maintained nominal interest rates at constant levels resulting in the real interest rates fluctuating from positive to negative all the time. Hence, Sri Lanka had a wide savings investment gap which had to be filled by relying on foreign savings which were attracted basically to the country via external borrowings. According to Bandara, when a country uses domestic savings for investment, the return on capital remains within the country, enabling it to benefit from such investments on the one hand and reinvest the same for further economic growth, on the other. But when a country uses foreign savings, that country will experience an outflow of the return on capital and therefore for further investment, it has to continuously rely on foreign savings. It would then trap that country in a vicious circle of foreign borrowings which in later years would be reflected in an undue growth of its external debt stock. This is exactly what has happened to Sri Lanka today.

High total factor productivity through high investment in R&D

Because there was no burden on the budget in the form of extreme external debt repayment commitment, both Singapore and Korea were able to invest heavily in research and development or R&D and create a facilitating environment to convert the fruits of such R&D into commercially viable and exportable products. This was responsible in building up a huge technology base in both countries. But, Sri Lanka on the other hand, due to budgetary constraints, lagged behind in R&D and therefore had to depend on cheap labour concept for investment as well as attracting foreign investments. This has two implications on the growth of the three countries under consideration. First, in both Singapore and Korea, the incremental contribution to economic growth arising from the use of technology and the combined outcome of engaging both capital and labour, known as total factor productivity, was significantly higher than that in Sri Lanka. The corollary of this development is that a smaller addition of both capital and labour in Singapore and Korea would bring in a higher economic growth. To attain the same growth, Sri Lanka had to use more and more capital and labour in varying combinations.

Sri Lanka’s low technology base and getting snared in middle income trap

The second implication of low R&D was that Sri Lanka had to depend on cheap labour for its economic growth. But, Sri Lanka’s growth is constrained because the golden era of cheap labour has now disappeared. On one side, its labour is not cheap anymore and it cannot compete with other cheap labour countries such as Bangladesh and Myanmar. On the other, without technology, it cannot move up in the ladder from a lower middle income country to an upper middle income country and finally to a high income country. Sri Lanka is now trapped in what is known as the ‘middle income trap’ in which it cannot neither move forward nor remain competitive among its peers. This was the breakout point of departure for the three players who had started the game with the same endowment set. Both Singapore and Korea made a quantum leap to the rich world, while Sri Lanka was left behind as an emerging economy forever.

Sri Lanka’s missed opportunity in 1966

This is in fact a sad story of missed opportunities. I have traced back this missed opportunity to 1966 when the Sri Lanka Government refused to follow a set of policy recommendations made by Gujarati economist B R Shenoy. I have discussed this missed opportunity in a previous article in this series under the title ‘The Ignored B R Shenoy Report: An instance of missed opportunity for Sri Lanka?’ (Available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/432905/The-ignored-B-R--Shenoy-Report-of-1966:-An-instance-of-missed-opportunity-for-Sri-Lanka). Shenoy who was hired by the then Minister of State and Deputy Prime Minister J R Jayewardene to report on the economic reforms needed to lift the economy from the depth to which it had fallen had submitted a rebellious report containing recommendations which had even outrivaled those that had been adopted by Singapore and Korea at that time.

Shenoy’s rebellious recommendations

In summary, his recommendations had been the following:

Balance the budget not by raising taxes which would further reduce the national savings but by halting the expenditure leakages in the form of unproductive subsidies, expansion of the state sector and non-rationalisation of the capital expenditure programs;

Denationalise the selected state corporations in fisheries, manufactures and trading areas so that they would not be a drain on the limited resources in the budget;

Generate surplus in the current account and use that surplus to finance increased capital expenditure programs thereby having a zero budget deficit;

Bring market discipline to other state enterprises by listing them in the stock exchange;

Give cash subsidies instead of commodity subsidies to the deserving;

Reduce the marginal tax rates since taxation destroys potential national savings into a bon-fire of public consumption;

Totally abolish import and export controls and float the Sri Lanka rupee. This was a totally rebellious recommendation since in 1966 even the developed countries had not gone for floating exchange rates;

Liberalise external trade fully to generate an assured inflow of raw materials for domestic industries which would in turn export quality goods to the market.

Compromising reforms through fear of losing power

It would be apparent that Shenoy’s recommendations were well ahead of the time, surpassing even those adopted by Singapore and Korea at that time. According to biographers of J R Jayewardene – K M de Silva and Howard Wriggins – JR had been impressed by these policy recommendations. However, when they were submitted to the Cabinet, according to JR’s biographers, Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake had chosen to kill them, believing that it was yet another ploy by JR to oust him from leadership. Hence, the policy package was dismissed and it remained a dusty document with JR till it was transferred to J R Jayewardene Centre in Colombo as a vital document.

Regaining missed window of opportunity

This was a window of missed opportunity for Sri Lanka. Bandara thinks that Sri Lanka need not live with a series of missed opportunities. His prognosis has been that the country can regain what has been lost by adopting a proper set of economic reforms and consistent economic policies. In my view, the present Coalition Government is the best for introducing such a reform program. It was the Coalition Government of David Cameron that rescued the UK from imminent bankruptcy in 2010. They did so by having one voice on policy reforms. Hence, there is no choice for the two constituent parties in the government – UNP and SLFP – but to speak in one voice rather than expressing in a multitude of diverse voices.

(W A Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])