Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 23 February 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Trade liberalisation has led to raise economic growth and reduce poverty in many developing countries across the world in recent decades. It contributes to growth and poverty reduction through different channels – job creation, product diversification, greater market access, capital inflows, technology infusion, innovation and

Trade liberalisation has led to raise economic growth and reduce poverty in many developing countries across the world in recent decades. It contributes to growth and poverty reduction through different channels – job creation, product diversification, greater market access, capital inflows, technology infusion, innovation and

competition.

Outward orientation depleting

Sri Lanka’s trade openness, defined as exports plus imports as a ratio of GDP, has narrowed over decades, despite the launch of trade liberalisation way back in 1977, much earlier than the neighbouring countries.

The country’s slow export growth has resulted in an expansion of the trade deficit over the years causing enormous balance of payments difficulties and external debt burden. The external imbalance has severely arrested the country’s growth potential, job creation and poverty reduction.

The ad hoc policies adopted by the successive governments over the years have had much to do with the country’s limited outward orientation.

Benefits of free trade

A number country studies conducted in the 1970s and 1980s provided strong empirical evidence against import substitution policies (promoting industrialisation by import controls) in favour of outward-oriented policies (trade liberalisation accompanied with free movement of capital, labour, technology and enterprises). The most prominent among them was the study conducted by the US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) under the direction of Anne Krueger and Jagdish Bhagwati in 1978.

Trade opening and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows are found to be the major driving force behind the success stories of East Asian economies. More recent examples are India and China in which outward-oriented economic strategies led to foster economic growth enabling millions of people to come out of poverty.

No country has been able to achieve economic growth and poverty reduction in recent decades without being open to the rest of the world.

SL’s trade openness shrinking

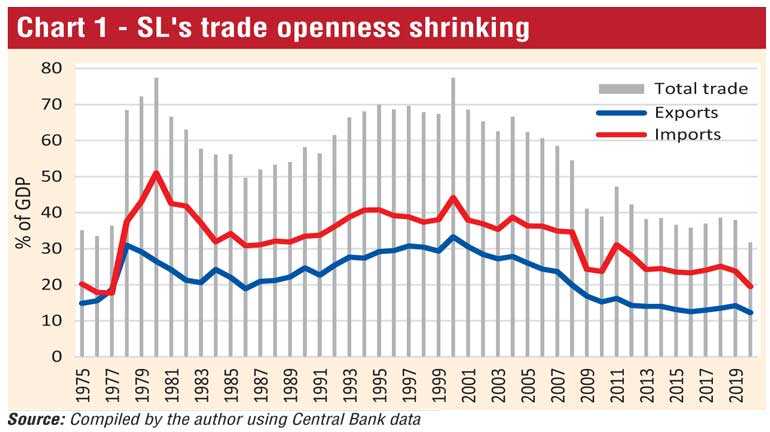

Sri Lanka saw substantial trade openness immediately after the economic liberalisation in 1977 (Chart 1). The total amount of foreign trade transactions rose from 36.4% of GDP in 1977 to 68.4% in 1978, and reached a peak level of 77.4% in 1980. That momentum did not prevail for long due to the eruption of the ethnic conflict in the North in the early 1980s and the youth unrest in the South in the latter part of the decade.

Both exports and imports rose in the 1990s and total trade recorded a peak level of 77.4% GDP by 2000. Since then, trade openness has declined continuously, and by 2020 it was only 31.7% of GDP, which is the lowest during the post-liberalisation period. Ironically, it was lower than the pre-liberalisation ratio of 35.1% of GDP in 1975.

Export performance dismal

The country’s export sector has not performed well during the post-liberalisation period. Export earnings recorded a substantial increase in relation to GDP in the immediate aftermath of liberalisation, but the momentum faded away fast in the subsequent years. Export earnings as a ratio of GDP reached a peak level of 33.3% in 2000, and since then it has declined continuously.

The ratio was down to 14.2%in 2019, and declined further to the lowest level of 12.2% last year due to the pandemic. Thus, the export performance experienced in recent years is much worse than the situation prevailed in the pre-liberalisation period.

Anti-export bias

In general, the country’s incentive structure has created anti-export bias over the years favouring non-tradables such as construction, domestic trade, finance, real estate business and speculative deals.

Even the Board of Investment (BOI), which was set up to promote export-oriented industries, has been granting generous incentive packages to the non-tradable sector, particularly infrastructure projects that include housing, property development, shops and offices, medical care and power generation.

Interest rates and the exchange rate have been mostly subject to Central Bank’s intervention throughout the post-liberalisation period, and hence, exporters have lost the gains that could have transmitted through free market movements of those rates.

Rigidly fixed exchange and interest rates have resulted in capital outflows, in terms of the “policy trilemma” or “impossible trinity”, as discussed in last week’s Daily FT column (http://www.ft.lk/columns/Policy-trilemma-poses-formidable-challenges-to-interest-and-exchange-rate-management/4-713226).

Meanwhile, the Government has been allocating huge amounts of public investment for infrastructure development during the post-conflict period.

Thus, even the moderate GDP growth achieved in recent decades was mainly driven by construction, financial services and allied activities, rather than export-oriented industries. Such growth cannot be sustained for long, as evident by now.

Technology and innovation backwardness

Sri Lanka still depends heavily on basic labour-intensive exports, mainly garment products which account for 50% of total export earnings. Other industrial exports are confined to a few low-tech products such as food processing, machinery and petroleum by-products.

By contrast, East Asian countries graduated years ago from basic industries to heavy industries like ship building and subsequently, to knowledge-based high value-added products such as computer chips, mobile phones, scientific equipment, medical apparatus and various other electronic instruments.

Those countries invested heavily in modern education and Research and Development (R&D). In Sri Lanka, on the contrary, the education system is not geared to prepare human capital for a modern knowledge-based economy.

The country’s expenditure on R&D is less than 1% of GDP whereas advanced countries spend 5–10% of GDP for the purpose.

Weaknesses in the country’s legal provisions with regard to intellectual property rights and patent rights too inhibit scientific innovations.

Trade imbalance hinders economic growth

According to the well-known theory introduced by Prof. Anthony Thirlwall of University of Kent in 1979, a country’s long-run growth rate is constrained by its export capacity and import demand. It is known as Thirlwall’ Law of “Balance of Payments – constrained economic growth”.

The larger the trade surplus (exports minus imports), the faster the economic growth. In the long run, therefore, no country can grow faster than that rate consistent with balance of payments equilibrium on current account, unless it can continuously finance ever-growing deficits by foreign borrowing which, in general, is impossible.

In terms of this law, Sri Lanka’s GDP growth rate cannot exceed 5.0% per annum, according to the writer’s computations.

Trade openness causes GDP growth

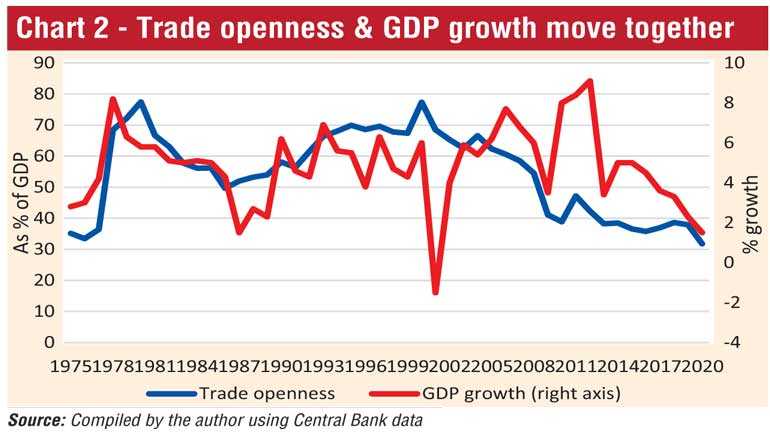

GDP growth is closely related with trade openness in the case of Sri Lanka (Chart 2). In parallel with the downward trend of trade openness during the last 15 years, GDP growth has decelerated continuously with the exception of the short-lived post-conflict economic boom.

The statistical tests carried out for this study reveals that causality runs one way from trade openness to GDP growth, but not the other way round. This means that trade openness causes GDP growth, but openness is not caused by GDP growth.

Given the high import content of Sri Lanka’s exports, faster export growth naturally needs larger volumes of imports.

In Sri Lanka, imports are highly sensitive to economic growth; 1% GDP growth results in 0.85% increase in imports, according to our estimates. Thus, as GDP grows, imports rise faster causing enormous expansion of the trade deficit unless there is concomitant growth in exports.

This is why the country’s external position has become extremely volatile by now with mounting debt commitments undertaken year after year to finance the balance of payments deficit.

Prospects for 2021

On a positive note, a dramatic recovery of the export sector is projected by the Export Development Board (EDB) for this year. Merchandise export earnings are projected to rise by 20% to reach $ 12.1 billion in 2021 from $ 10.1 billion last year. This together with service exports projected at $ 3.6 billion would hit nearly a $ 16 billion target of total exports in 2021, according to EDB.

Such export growth will certainly generate higher GDP growth. According to Central Bank’s projections, GDP growth is to rebound 5.5-6.0% this year with per capita GDP reaching $ 4,000.

The projected economy recovery, however, will depend to a large extent on how fast COVID-19 pandemic is going to be eradicated.

Policy directions

The Government’s policies need to be conducive to foster the export sector so as to achieve the optimistic export and growth targets.

Apparently, there are concerns over the Central Bank’s directive issued last Friday to exporters to immediately convert 25% of their export earnings through licensed banks. Exporters are reported to have expressed their displeasure over this regulation lamenting that it would escalate their transaction costs and limit flexibility in decision-making during the current pandemic-hit business environment.

Given the country’s weak competitive edge, appropriate bilateral collaborations with advanced countries through Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) are a useful means to catch up vast opportunities in the global trade environment. However, restoration of economic stability is a prerequisite to harness such opportunities.

A long-term trade policy based on outward looking economic strategies, instead of the currently practiced arbitrary tariff adjustments and import controls, is the need of the hour at least to slow down the country’s drift towards closed economy.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and Senior Visiting Fellow of the Advocata Institute. He is a former Director of Statistics of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, and reachable through [email protected])