Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 2 August 2023 00:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Engaging in insider trading is considered a crime as such behaviour unfairly benefits ‘insiders’ at the cost of other investors

There are two purposes for this article:

There are two purposes for this article:

1. To examine the emphatic statement Professor Premachandra Athukorala made at his interview with Pethikada on 11 July 2023 (and further elaborated in his Daily FT Guest Column on 14 July 2023, https://www.ft.lk/columns/Some-thoughts-on-debt-restructuring-in-Sri-Lanka/4-750578) that the holders of International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) have received a better deal than they had expected.

2. To examine a different, related question. That is, whether there are reasons to suspect that the observed increase in demand (bidding) for Sri Lankan ISBs since 3 May 2023 (apparently, the day discussions/negotiations leading to the ISB restructure plan was commenced) until 28 June 2023 (the day before the day of the official announcement of the Scheme on 29 June 2023) was caused by ‘insider trading’. Insider trading is buying (or selling) securities using information privy to insiders.

This question/aspect is directly related to (1) above, because any consistently upward demand for ISBs during a time period before the entire market came to know about the restructuring plan could be considered as a proof that the ‘insiders’ had firmly believed that the scheme would be better than the market’s expectations. Moreover, examination of this suspicion is important as it may give us some clues as to who in the market may have benefitted from buying ISBs perhaps using insider information that was available to them prior to the announcement of the scheme.

Have the holders of International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) received a better deal than they had expected?

One of the widely accepted methods available to answer the above question is examining the movement in the prices of Sri Lankan ISBs being traded in the secondary ISB market. We need to focus only on the price movements of the ISBs after the public announcement of the proposed restructuring plan (the Plan). The direction of the price movement in response to the ‘new information’ contained in the Plan would tell us whether the ‘new information’ was treated as positive or negative by the market. If there was an increase in the price, it was because the market had considered the ‘new information’ as positive. The magnitude of the increase would indicate the positive ‘expectation gap’, i.e., what the market had expected and what it has received.

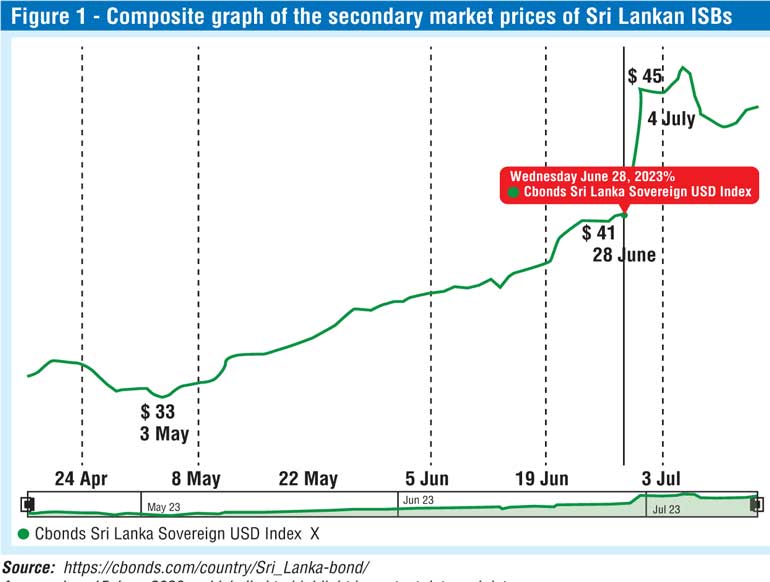

The composite (index) graph of 12 Sri Lankan ISBs with different maturities amounting to a face value of $ 12.55 billion, currently outstanding and trading in the secondary markets, is given in Figure 1. The vertical axis of the graph indicates the composite US$ price of one ISB. (The Face value of a bond is $ 100).

Figure 1 covers the period from 15 April 2023 to 15 July 2023. The thin back vertical line labelled ‘Wednesday, June 28, 2023’ (i.e., just one day prior to the announcement) shows a composite price index of 41 ($ 41). From 29 June to 30 June the price has jumped sharply to $ 45, an increase of 10% within two days. Again, from 1 July to 4 July, the index has increased by 1.2% to $46. After that, from 5 July to 10 July, there has been a slight drop in the index (presumable due to new negative information and/or ‘profit taking’). Since 11 July the index has started to rise again. (The dates and values are approximations).

As the above composite graph of ISB prices clearly shows, the price index (consisting of all outstanding Sri Lankan ISBs) has risen by about 11.2% since the announcement of the Plan. This has happened despite receiving some important negative information by the ISB market during this period (e.g., downgrading of SL rating from CC to C by Flitch rating agency just few days after the government announced its debt restructuring scheme, https://www.fitchratings.com/site/re/10111579). The buyers were willing to pay more (bid and buy) just after the announcement of the Plan compared with what they were willing to pay just before the announcement). As a result, the existing holders of the ISBs have gained. It is very clear that the ISB market has considered that the proposed plan exceeded their expectations. Therefore, the statement made by Professor Athukorala is empirically supported.

Is there evidence to support a suspicion that insider trading has taken place?

As the average reader may not know much about insider trading it might be helpful to begin with a brief description of insider trading and why it is considered a crime. This will also help the readers to appreciate the need to examine its possible presence in the trading prior to the announcement of the Plan for restructuring Sri Lankan ISBs.

As the average reader may not know much about insider trading it might be helpful to begin with a brief description of insider trading and why it is considered a crime. This will also help the readers to appreciate the need to examine its possible presence in the trading prior to the announcement of the Plan for restructuring Sri Lankan ISBs.

Insider trading

Insider trading is buying or selling (trading in) publicly-traded securities (e.g., bonds, shares) by someone who has non-public material information about the issuer of the securities. Such non-public information includes the current or future position of the issuer and the current decisions or future plans of the issuer received from managers, consultants, agents, negotiators, employees of the issuer and any person (natural or legal) who has private access to such information. With regard to Sri Lankan ISBs, the issuer is the Government of Sri Lanka.

Why insider trading needs to be identified?

Engaging in insider trading is considered a crime as such behaviour unfairly benefits ‘insiders’ (those who have access to information that is not available publicly) at the cost of other investors. In addition, perhaps more importantly, insider trading obstructs the ‘efficient’ functioning of securities markets and diminishes the trust of the investors with farfetched adverse consequences. Because of the gravity of this behaviour, most countries have laws prohibiting insider trading. These laws prescribe severe penalties including imprisonment for proven cases.

Insider trading in share and bond markets are drawing increasing attention of regulatory authorities such as SEC (America), ASIC (Australia), (Australian Financial Review, 13 October 2020). They are adopting many measures such as increased oversight, surveillance, announcing of best practice guidelines and taking legal actions against perpetrators. In its publications, the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSC, an association of organisations that regulate the world’s securities markets) notes the malpractices of market intermediaries (https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD661.pdf). IMF also has published a number of discussion/staff papers with the intention of finding ways to address this issue. Their discussions centre on insider trading and other malpractices in debt markets which include corporate bonds and ISBs (https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781589063341/ch038.xml#ch38fn06).

Direct investors in securities (e.g., banks, insurance companies, superannuation funds, retail investors, private investors) and asset managers/fund mangers who invest in securities on behalf of their clients are sometimes accused of engaging in non-transparent trading practices with regard to allocation of securities and subsequent trading; non-adherence to rules against money laundering; keeping the assets of criminals, corrupt politicians and related powerful individuals under a veil of secrecy; and passing of insider, price-sensitive material, information to their clients in subtle and not-so-subtle ways before such information is publicly available to the market. Despite its apparent presence, the law enforcement authorities find tracing insider transactions and prosecuting perpetrators extremely challenging.

Ways to identify the presence of insider trading in a particular security (e.g., ISBs)

There are several ways to identify the presence/incidence of insider trading in securities. The method (or methods) being adopted depends on the role, purpose and immediate aim/s of the investigators. For example, corporate watchdogs such as SEC and ASIC may use surveillance, transaction and communication records, forensic accounting/auditing evidence, etc., to find hard evidence with the aim of prosecuting the perpetrators. On the other extreme, academics would gather market-price data and other relevant information for the particular security (bond or share) and perform, for example, an ‘event study’. To structure and perform a robust event study, it is essential to have (1) a precise log of informational events (including the date and time of price-sensitive public announcements by the issuer and/or its agents) with which a time-line can be accurately drawn, (2) daily/hourly market price data with offer and bid spreads.

There are several ways to identify the presence/incidence of insider trading in securities. The method (or methods) being adopted depends on the role, purpose and immediate aim/s of the investigators. For example, corporate watchdogs such as SEC and ASIC may use surveillance, transaction and communication records, forensic accounting/auditing evidence, etc., to find hard evidence with the aim of prosecuting the perpetrators. On the other extreme, academics would gather market-price data and other relevant information for the particular security (bond or share) and perform, for example, an ‘event study’. To structure and perform a robust event study, it is essential to have (1) a precise log of informational events (including the date and time of price-sensitive public announcements by the issuer and/or its agents) with which a time-line can be accurately drawn, (2) daily/hourly market price data with offer and bid spreads.

What evidence do we have for our case at hand?

Is there evidence to support a suspicion/claim that insider trading has taken place in Sri Lankan ISBs?

For this purpose, I will use the same graph (Figure 1) used earlier. However, I will ignore the section of the graph starting from the day the Plan was publicly announced (i.e., from 29 June, 2023) as it is irrelevant for answering the question at hand. In other words, any trading based on publicly available information cannot involve insider trading as everybody in the market had access to such information. Accordingly, I will focus on the section of the graph from 3 May 2023 (apparently, the day discussions/negotiations leading to the ISB restructure plan was commenced) until 28 June 2023 (the day before the day of the official announcement of the Plan).

The composite price on 3 May 2023 was about $ 33. This price has increased to $ 41 (by 24%) by 28 June 2023. A price increase of 24% in less than two months is very significant in any kind of investment. The graph clearly shows that the secondary market prices of all ISBs have been gradually and consistently increasing since 3 May (around the date of the commencement of the negotiations) until 28 June, i.e., the day before the announcement of the scheme. Apparently, this price increase has occurred despite the absence of any public announcements to the market by the relevant authorities or unmixed, positive news streamed by financial and other media.

How could the market price of ISBs consistently rise despite the absence of new positive information available to the ‘entire’ market? A theoretically plausible explanation is that some investors have been buying ISBs using information made available to them by insiders. It may be relevant here to mention about the news reported in the financial press about the involvement of a group of Fund/Assets Managers (who are managing their clients’ investments in Sri Lankan ISBs) and their agents in the discussion/negotiations/proceeding leading to the restructuring plan (for example, Reuters, 4 February and 14 April 2013). Apparently, the designing of the plan was preceded by a meeting of the international bondholders and Sri Lankan Government officials together with their financial advisors in the second week of April 2023.

An alternative explanation a layman might give is that the market has evaluated/interpreted the already available data and information and has acted upon such evaluations/interpretations. However, such an explanation is unsound because the theory of financial markets tells us that in efficient markets (such as international ISB markets) all the available information about a security will have been already reflected in the going price at any point in time. Accordingly, new information is required for prices to move either way.

Another theoretical reason for rejecting this explanation is that a ‘random behaviour’ is expected from the market players in the absence of definitive pointers. As a consequence, the negative sentiments/interpretations of some investors would more or less cancel out positive sentiments/interpretations of other investors. Hence, the price of a security would almost remain the same or stagger in a random manner until new information is available.

One may also argue that the positive news about the issuer (e.g., the receipt of the first instalment from the IMF under its four-year Extended Fund Faculty (EFF) program, and the need for debt restructuring as a prerequisite for releasing the second instalment in September as emphasised by the IMF) has apparently caused a positive sentiment in the ISB market during this period. However, a strong counter argument we can make is that such positive news should have been cancelled out by the negative news and data that were circulating in international financial media. For example, on 19 May 2023, Fitch Ratings Agency downgraded Sri Lanka’s Long-Term Foreign-Currency (LTFC) Issuer Default Rating (IDR) to ‘RD’’ (Restricted Default).

Moreover, the macroeconomic indicators displayed on sites being used by ISB investors were predominantly negative during this period raising doubts about the ability of Sri Lanka to repay its ISBs and other debts (https://cbonds.com/indexes/?viewTree=1&country=4-cn4&). Some sites displayed notices which explicitly discouraged investing in SL ISBs (https://www.bondsupermart.com/bsm/general-search/sri-lanka).

Although there is no direct evidence (e.g. definitive records, communications) to prove the occurrence of insider trading, we have presented indirect evidence by way of observed ‘price behaviour’ of ISBs. How did the price of all the ISBs consistently increase (from $ 33 to $ 41, by 24%) from 3 May 2023 until 28 June 2023, despite the absence of positive announcements or any kind of direct communication by the Sri Lankan Government or by its agents (e.g., CBSL) with all the bondholders? It is not possible to make a convincing argument that ISB prices kept increasing because of any positive information received by the entire market through public media during the relevant period. At best, the information received by the market was mixed.

In such a context, it is appropriate to form a strong hypothesis that ‘principals’ or ‘agents’ who were privy to insider information have acted upon such information, or have passed such information to their clients, perhaps with a recommendation to buy Sri Lankan ISBs. However, we are unable to test this hypothesis in a robust manner without access to a complete log of events with specific dates and times on which the issuer or its agents made announcements to the entire ISB market (or made communications with all bondholders).

Concluding comments

The restructuring plan needs to pass the test of ‘fairness’ at least for gaining legitimacy in the eyes of the people. If the original investors who bought the ISBs in the primary market are still holding the bonds, the Government and the people of Sri Lanka have a moral duty, on top of contractual obligations, to honour the commitments as best as they can because these investors by now have made a huge realised or unrealised loss. However, it is likely that the majority of original investors who bought ISBs in the primary market had sold their holdings in the secondary market by the end of November 2022, when the prices reached a bottom of about $ 30, incurring a loss of about 60-70%. Hence, the restructuring plan most probably would not benefit these original investors.

On the contrary, it is more likely, for example, that the new investor who had bought the bonds from the secondary market, at $ 33 on 3 May 2023, by now has made an unrealised profit of 39% (calculated at the current price of $ 46 per bond). This is a direct result of the restructuring plan.

Speaking about hard evidence of insider trading, as we do not have access to a list of original bondholders, current bondholders and a complete record of their transactions, we are unable to ascertain the profit (or losses) made by any individual investor. It is a well known fact that identities of bondholders are usually not known to the issuer or even to the regulatory authorities. Some investors invest through nominees. Fund managers and institutional investors apparently keep the identity of their clients a secret. Only a forensic audit, backed by law enforcing authorities could provide definitive answers to the concerns raised in this section of the paper regarding insider trading.

Although it might sound beyond the scope of this article, I would like to make the following two remarks based on my evaluation of the entire DDO scheme as a self-imposed prerequisite to embark on evaluating the ISB restructuring plan. In a way, studying of DDO was necessary because the ISB restructuring plan was part of (embedded in) the DDO.

The first remark is do with the fairness of the scheme: It is clear that the DDO scheme has apportioned the heaviest burden on Employees Provident Fund (EPF). It has been estimated that total debt relief from EPF (in other words, total burden/value reduction of EPF) is about 40-50% (Athukorala: https://www.ft.lk/columns/Some-thoughts-on-debt-restructuring-in-Sri-Lanka/4-750578). In comparison, the ISBs are thought to have been given a ‘haircut’ of about 30% (excluding an estimated interest rate adjustments valued at 5%), which is anyway less than they had expected.

However, in reality, the haircut will affect bondholders in three different ways if they were to hold onto the bonds until its maturity and receive $ 70 per bond: original bondholders who are still holding onto their bonds would make a loss of about $ 30 from each bond they bought at the face value of $ 100; other bondholders who bought bonds at prices above $ 70 will lose an amount of dollars equivalent to the difference between $ 70 and the price they paid, for example a bondholder who paid $ 80 would lose $ 10; bondholders who paid $ 70 or less would lose nothing. (These approximate arithmetics, which ignore required rate of return of the market including time value of money, duration, etc., are just good enough to understand the direct implications of the haircut on bondholders).

Interestingly, a current ISB bondholder who purchased the bonds, for example, on 3 May 2023 at $ 33 has already made an unrealised profit of around 39%, given that the current market price is around $ 46. They have the chance of making more profits in the future, for example, if they hold on to the bond till its maturity and receives $ 70, the arithmetic profit would be 112%. We need to compare these with the estimated 40-50% loss the members of the EPF are about to bear. In contrast, the shareholders of the banks, although expected to bear ‘residual risks’ of any eventuality, have been allowed get off scot-free.

The second remark, relates to the competence and transparency of the Government of Sri Lanka (including the Ministry of Finance, Central Bank of Sri Lanka and their advisors and agents). Apparently, Professor Lee Buchheit, nicknamed ISB Restructuring Guru, had called for these attributes/qualities from the Sri Lankan Government and their ‘team’ well before they commenced the negotiations leading to the restructuring plan (Cassim, Daily FT, 6 June 2022: https://www.ft.lk/top-story/Sovereign-debt-restructuring-global-guru-s-do-s-and-don-ts-for-SL/26-735801). I leave it to the readers to make their own judgements in this regard.

(The writer is a professional as well as an academic in finance with over 40 years of experience in the fields of accounting and finance. He is a former head of the disciplines of Finance and Financial Planning at Deakin University in Australia. Currently, he is an academic attached to the University of Melbourne.)