Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Monday, 29 July 2019 01:55 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A Hole in the Pocket

In a recent panel discussion on Sri Lanka’s debt sustainability – nicknamed A Hole in the Pocket – jointly organised by the Marga Institute and the Open University, two leading economists – Central Banker turned University Don Sirimevan Colombage and Bureaucrat turned Management Expert Anura Ekanayake – opined that the debt issue is critical for Sri Lanka in the next five years despite the positive view taken by the IMF and the Central Bank. They, therefore, recommended that urgent way-out strategies should be adopted by the country to get out of the existing debt trap. The discussion was moderated by another top economist, namely, IPS Head Dushni Weerakoon.

Domestic debt is ‘We owe it to ourselves’

Ekanayake, highlighting the differences in the country’s debt stock as reported by the Ministry of Finance and the Auditor General, said in his brief presentation that, of the two types of debt contracted by the Government, foreign debt is more critical since the country has to find foreign exchange to repay them. His contention was that domestic debt does not pose such a problem since it can be repaid by the Government by printing money, though it is not the proper way to address the issue. His contention is akin to the more appropriate description of domestic debt as something which the nation is owing to itself. Hence, the repayment of domestic debt is just an internal redistribution of assets among different economic entities.

Foreign debt involves a resource outflow

Foreign debt repayment, in contrast, is an outflow of resources from the country and, to that extent, the country loses resources available for investment in productive assets. According to Ekanayake, this outflow could have been one of the main reasons for the decline in the country’s growth rate in recent years. If growth is not forthcoming at the required rate, Sri Lanka, said Ekanayake, would be caught up in ‘an early middle income trap’, a condition that would prevent a country from moving from middle income to high income.

He made two, among others, suggestions to alleviate the country’s debt problems. One was to increase Sri Lanka’s growth potential by releasing presently domiciled females to the labour market. This would help Sri Lanka to overcome for a temporary period the emerging shortage of labour due to the low fertility rates and the ageing of population.

It is STEAM and not mere STEM that is necessary

The other one was to spend more on the development of human capital – a kind of a smart capital in today’s parlance. His argument was that Sri Lanka’s education system should be geared to help students to acquire knowledge in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics or STEM, to meet the demand for smart workers by both the government and industry.

However, there is growing acceptance now by industry that STEM should be broadened to accommodate creative Art, so that education reforms should concentrate on STEAM rather than just STEM. Ekanayake’s prescription for rapid economic growth is valid since the world is now moving to the Fourth Industrial Revolution or Industry 4.0 in which production comes from digital knowledge and not from traditional human knowledge.

For the sake of rapid economic growth, it is, therefore, necessary for both blue-collar workers and white-collar workers to convert themselves to be digital-collar workers. STEAM is the way to achieve that goal.

Debt sustainability

Colombage concentrated his presentation solely on Sri Lanka’s external debt sustainability. IMF has defined debt sustainability, presented Colombage, as a situation in which ‘a country can meet its current and future external debt service obligations in full, without recourse to debt rescheduling or the accumulation of arrears and without compromising growth’. It is necessary to further analyse this definition to identify its validity or otherwise.

IMF’s definition is faulty

In my view, the IMF definition is faulty, since it talks about only the current and future resource availability in a country to repay the maturing debt and pay interest on its existing debt stock. It does not talk about how prudently a country has acquired foreign exchange resources to gain this capability. If it is done through continuous further borrowing, then, it would simply add to the present debt stock snaring the country in what is known as ‘the debt trap’.

This situation arises when a country has not earned enough foreign exchange to repay its debt out of the investments it has made by using the debt proceeds. The failure to earn foreign exchange may be due to using the debt proceeds in unproductive investments or in consumption or in investments that cater solely to the domestic market.

In either case, the country has to borrow abroad to service its debt and acquiring foreign exchange by borrowing will enable the country to meet IMF’s debt sustainability requirements. But it is not a prudent way of acquiring long term debt sustainability since, instead of getting out of debt, the country will be driven eternally to be in debt.

To borrow more to repay debt

The present external debt problem in Sri Lanka is exactly in that situation. The proceeds of the sovereign bonds have been used by Sri Lanka to finance the government budget in general. When the budget is running a deficit in its current account meaning that the government does not earn enough even to meet its current consumption, a part of the bond proceeds is used for consumption. Even when the loan proceeds have been used for investing in projects, some of the projects like sports stadiums are meant for the local market without earning foreign exchange to repay the loans and pay interest on them.

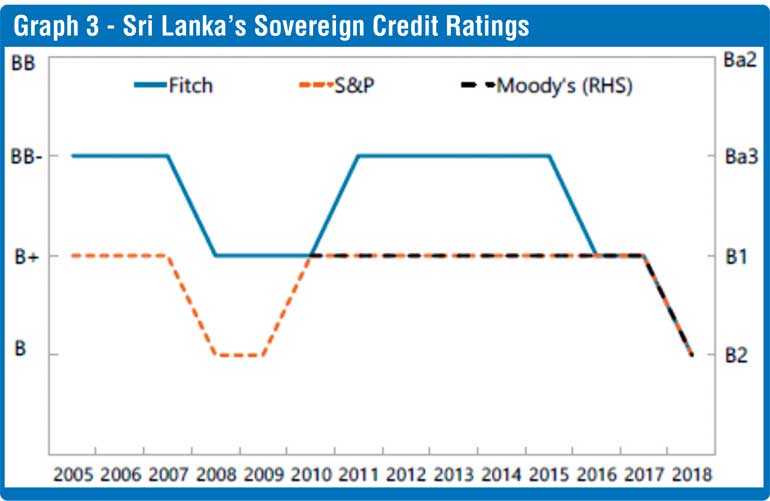

Hence, there is always a shortfall of foreign exchange earnings which have to be met by further borrowing from the market. When Sri Lanka goes to the market, as all the three rating agencies have warned, the country runs the risk of not being able to raise sufficient funds or if it is able to do so, of raising them at high interest rates. Either way, Sri Lanka is presently faced with a debt recycling risk. This possibility is not captured by the IMF definition on external debt sustainability.

When Sri Lanka goes to the market, as all the three rating agencies have warned, the country runs the risk of not being able to raise sufficient funds or if it is able to do so, of raising them at high interest rates. Either way, Sri Lanka is presently faced with a debt recycling risk.

Private foreign debt is also a problem

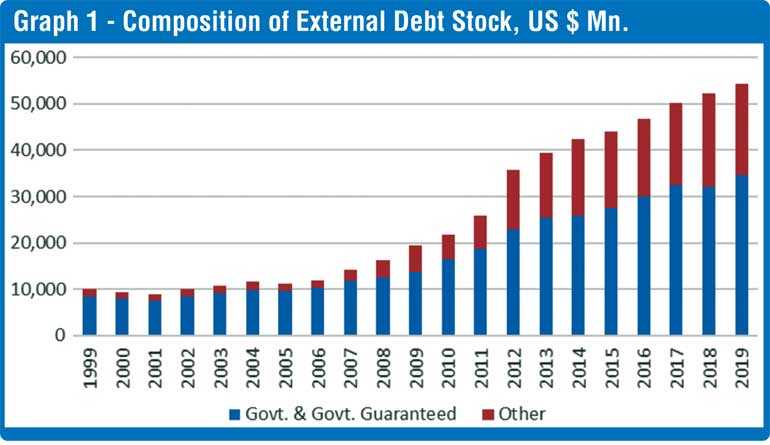

A popular belief is that Sri Lanka’s foreign indebtedness is solely confined to what the government has borrowed from external sources. Quite contrary to this belief, there is a sizeable amount of private sector borrowing from external sources which is on the increase since 2012. As presented by Colombage in Graph 1, the total foreign debt of the country in 2019 will amount to some $ 56 billion and out of that amount, about $ 21 billion had been contracted by the private sector.

These private sector entities may have rupee funds to repay these loans. But the national economy may not have enough foreign exchange to convert those rupee funds into foreign currencies to make the repayments. This was the situation faced by countries like Mexico and Argentina which ran into external debt problems in 1980s and 2010s, respectively. Both countries had to default foreign debt repayments with adverse consequences relating their international borrowing capacity as well as ability to continue with high economic growth.

Sri Lanka’s problem had further been compounded by the fact that the private sector has made these borrowings exclusive from commercial markets with very short grace and maturity periods.

Fragile balance of payments

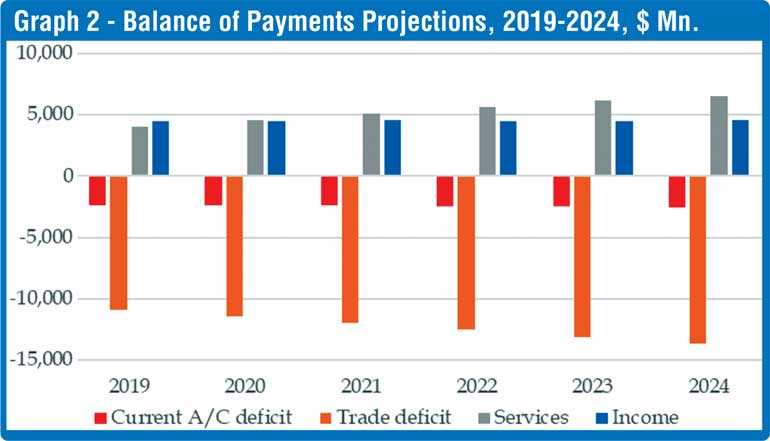

According to the best projections available, Sri Lanka’s balance of payments in the next five years will be highly fragile. As shown in Graph 2, it is projected to have a stubborn current account deficit which has been augmented by an equally stubborn trade deficit. The current account in the balance of payments records on the receipt side, the flow of foreign exchange into Sri Lanka by way of exports, sale of services, income receipts and worker remittances into the country.

On the payments side, it has imports, purchase of services, payments on account of incomes earned by foreigners as dividends or interest and out-remittances made by Sri Lankans to entities outside the country. Any shortfall in the current account which is the case with Sri Lanka all the time will have to be filled by using the existing foreign exchange balances or borrowing abroad or attracting investments in to the share market or bond markets or getting foreigners to invest in Sri Lanka known as foreign direct investments or FDIs or a combination of all these sources. Sri Lanka’s present situation is such that its insufficient foreign exchange balances cannot be used to repay external debt without detrimental effects.

Investments in the share or bond markets consist of hot money that comes in and goes out frequently based on adverse or favourable global developments. With the expected interest rate hike in the United States, it is likely that this hot money will flow out of Sri Lanka making it an unreliable source of filling the gap in the balance of payments. FDIs are also not forthcoming to Sri Lanka in adequate amounts compared to India, Myanmar or Vietnam.

Hence, the only worthwhile source for filling the gap in the balance of payments in the next five year period will be making further borrowings and at that, borrowing from commercial markets. But the downgrading of Sri Lanka’s sovereign ratings by all the leading rating agencies in the recent past, as presented in Graph 3, will pose a serious problem for the country to tap this market effectively. This is indeed a situation which Sri Lanka has to take into account seriously.

Convenient assumptions by IMF

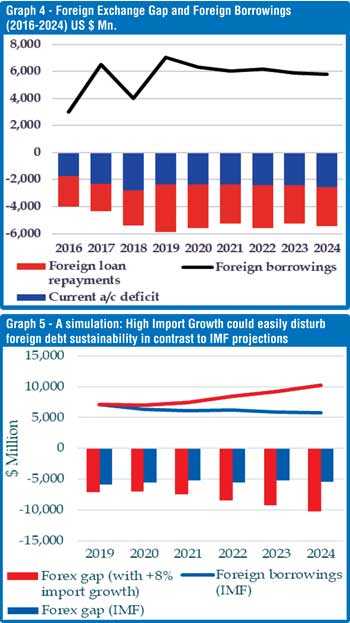

A debt sustainability assessment made by IMF in May 2019 for the period from 2019 to 2024 came under Colombage’s scrutiny in his presentation. The IMF’s assessment has been based on the following assumptions. First, the annual foreign borrowing requirement during the period has been estimated at $ 5.5 billion and of this amount, $ 3 billion or 55% has been taken out as what is needed for debt repayment. Thus, the balance $ 2.5 billion has been earmarked for financing the gap in the current account of the balance of payments in each year under consideration.

This is exactly Sri Lanka’s present current account gap and to maintain the gap at this uniform level, it is necessary for the country to shrink its trade deficit significantly over the coming years. For that, IMF has assumed that economic growth in the coming years would be around 4-5% annually and import and exports would grow at a uniform rate of 5% per annum. Thus, if any of these macroeconomic variables deviate from what has been assumed by IMF, it would derail the whole analysis. IMF’s projections have been presented in Graph 4.

An alternative debt sustainability

Colombage has reassessed Sri Lanka’s debt sustainability assessment during 2019 to 2024 under different assumptions. The main change he has made is the increase in the import bill by 8% annually, while keeping exports at the assumed rate of 5% per annum. Under these circumstances, Sri Lanka will have a wider foreign exchange gap as presented in Graph 5. Another important factor which has been ignored by IMF is the declining remittances flows to the country. In the past, these remittances standing at around $ 7 billion per annum was responsible for financing about 70% of the trade deficit in the country. With the current declining trend, the gap estimated by Colombage would be even larger.

Be on alert and not complacent

While IMF’s debt sustainability assessment would make Sri Lanka complacent, Colombage’s alternative assessment would put Sri Lanka’s authorities on alert requiring them to take early remedial action to convert the country’s foreign debt problem to a more acceptable form.

However, the permanent solution lies elsewhere and this will be handled in the next article in this series.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)