Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Monday, 18 April 2022 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Yes, as we all now know too well, denial is not a strategy. But neither is going to the IMF. Even though it’s the first step in the long journey towards stabilisation and recovery, it is not a strategy. A strategy, or program as it is called in IMF-speak, still needs to be developed. Since this program will be Sri Lanka’s 17th, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose one may say. And, in many ways, such pessimism would not be wrong. But this program is different. It marks the first time Sri Lanka embarks on a three-way agreement, involving creditors, as well as the usual government and IMF duo.

Yes, as we all now know too well, denial is not a strategy. But neither is going to the IMF. Even though it’s the first step in the long journey towards stabilisation and recovery, it is not a strategy. A strategy, or program as it is called in IMF-speak, still needs to be developed. Since this program will be Sri Lanka’s 17th, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose one may say. And, in many ways, such pessimism would not be wrong. But this program is different. It marks the first time Sri Lanka embarks on a three-way agreement, involving creditors, as well as the usual government and IMF duo.

Same, same but different

Program 17’s private creditor involvement grants the IMF greater leverage than in past negotiations. First, creditors will be loath to settle in the absence of a program, especially as Sri Lanka has no experience of default. Not to mention our persistent scarcity of political stability or policy coherence. Second, opportunities for reform often correspond to the severity of a crisis. As argued in ‘A Crisis Manifesto’, the breadth and depth of this crisis may constitute as significant a shift in Sri Lankan economic thinking as the Great Depression and the rice queues of the 1970s. Already reforms which appeared fantastical but a few months back, now seem eminently practical. Third, it will be the first time Sri Lanka obtains an extended facility under a non-UNP government. Meaning, for the first time since Independence, an IMF program will be the primary framework within which SLFP/SLPP economic policy-making and budgets must operate for an extended period of time.

Therefore, the design of this program could shape economic policy-making for the next generation, and along with it, Sri Lanka’s last possible chance for serious economic-breakthrough and prosperity (alas, far too often, demography, like geography, becomes destiny). The substance of this program is far too important to be left solely in the hands of the grey suits at the IMF, Treasury and Central Bank. All sections of society – Government backbenchers, Opposition, private sector, civil society and academia – must think hard and work harder to shape this historic program.

The constraints of international institutions, creditors and domestic politics are real. But Sri Lanka and Sri Lankans still have a great deal of agency. This is true of our own history – such as in 1977 when we liberalised via an IMF program, but also set-off on the misguided accelerated Mahaweli adventure. The history of other countries too illustrates the agency countries have even when deeply enmeshed within an international system. A recent Twitter thread on the supposed French socialist turn away from austerity in 1983 illustrates this well. And that agency must be used, and used wisely. Even though there is now broad consensus on the direction Sri Lanka must take; the priorities, details and sequencing of Program 17 must be fleshed out and implemented. That requires a national conversation and thereby some semblance of national consensus.

Cosmetic compliance

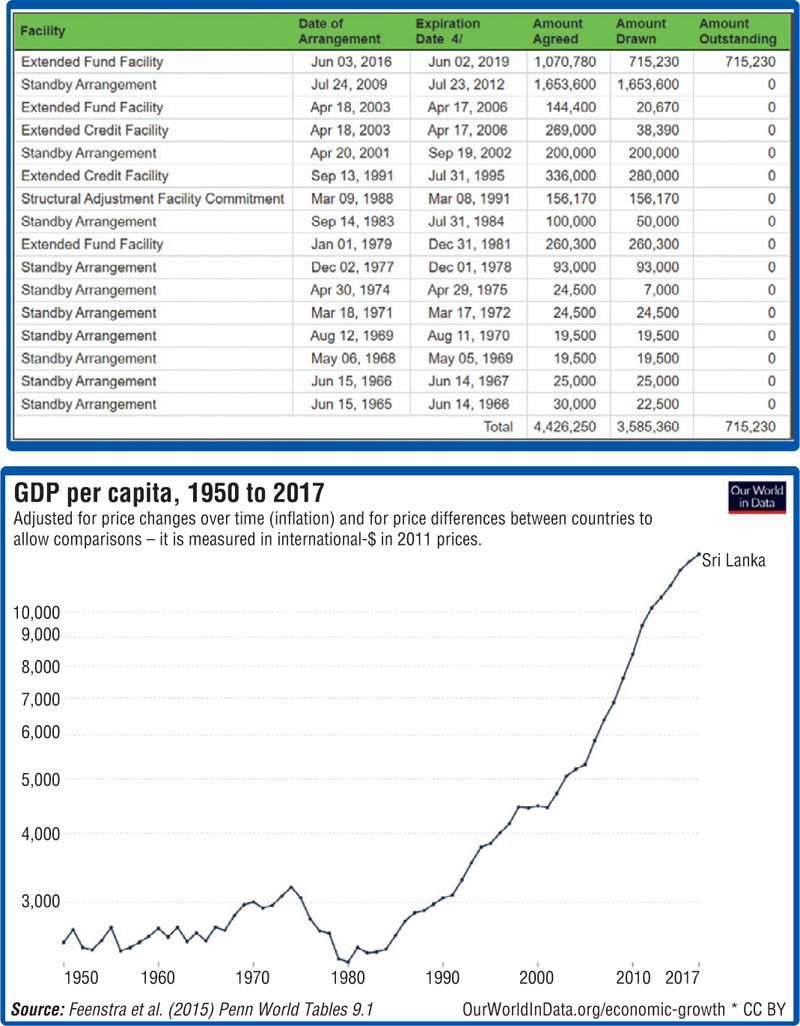

Sri Lanka’s first IMF program was in 1965. Since then we have entered into nine other standby arrangements and six extended facilities. Of these 16 programs, only six were completed.

In reality, our completion rate is even worse. Only two of the completed programs were extended facilities, focusing on long term structural reforms. And they were both prior to the 1990s. The remaining four were stand-by arrangements targeting short-term stabilisation rather than long-term structural change. Refer Figure 1. (https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/extarr2.aspx?memberKey1=895&date1key=2018-09-30)

But we are getting ahead of ourselves: what is an IMF program in the first place?

An IMF program is simply an agreement where a government commits to quantitative targets (such as a budget deficit target) and structural reforms. In return, the government gets access to finance, which is released in stages, upon completion of specific milestones. The IMF also issues report cards – called reviews – at regular intervals on program performance. These are used to gain credibility with creditors and donors, unlocking further access to finance.

Plus ça change

As noted earlier, of the two main types of IMF programs, extended facilities are the more ambitious. They last longer and are intended to rectify structural problems. When we review the six extended facilities Sri Lanka has obtained, the same themes keep propping up over the decades:

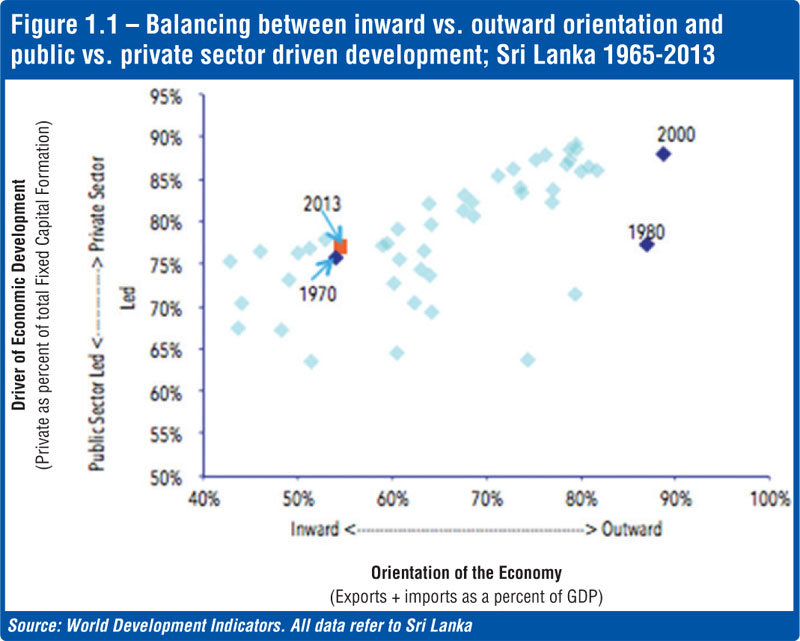

When Sri Lanka requested its first extended facility in 1979, prices were controlled, imports were licensed, economic activity was largely in government hands and social transfers were riddled with inefficiency. By 1994, following a number of extended facilities, Sri Lanka had greatly liberalised. Price controls were lifted (including the exchange rate), imports flowed freely with a simple three-band tariff structure (capped at 35%), exports boomed and SOE privatisation boosted productivity. Less success was found in reducing public expenditure, increasing revenue and targeting social transfers. However, there was some progress here too, under the conceptual aegis of the Administrative Reforms Commission (Wanasinghe Commission) recommendations. In fact, the numbers are clear. Sri Lanka’s economy took-off only after its first extended facility in 1979. Economically speaking, the foundations for our relative rise from misery were laid in the late 1970s and 1980s. Refer Figure 2.

Despite the absence of IMF programs between 1994 and 2001, this trajectory continued and even accelerated in some respects. SOEs like SLT, Queen Elizabeth Quay and Air Lanka were privatised. The investors – Nippon Telecom, Maersk and Emirates – brought in FDI and world-class technology and talent. In contrast to the current crisis, following the Asian Financial Crisis, rather than closing borders, Sri Lanka signed its first free trade deals, with India and Pakistan. Capital markets developed. The private sector grew. Free trade zones kept expanding. Services exports gathered momentum. Even though Sri Lanka, unlike its competitors, was unable to add a major manufactured export in this time (the apparel and solid-tyre duet began in the late 1970s and early 1980s), overall things were going in the right direction. Growth was relatively robust, at 5.3% for the decade, despite the albatross of the civil war.

Turning back the clock

It is only in 2005 that shades slumbering since 1977 roused themselves and drifted forth from the Medamulana mirkwood. They stealthily transformed the Treasury into a tower of caprice and closed economics. Price controls and tariffs started creeping back, increasing consumer and input good prices, while only benefiting a small coterie of politically connected protectionist and parasitic businessmen. By 2015, Sri Lanka had turned full circle: we were nearly as closed an economy as in the 1970s. Refer Figure 3.

Privatisation not only stalled but reversed. Government expenditure rose via debt fuelled expansion of the public service and white elephant infrastructure. Gorging gluttonously at the over-liquid trough of global capital markets also resulted in heavy capital inflows. These precipitated overvalued exchange rates, which were further inflated by hot-money pouring in following the war’s end. In relative terms, imports rose and exports fell. This debt party created the enabling conditions to reverse the 1979 to 2004 consensus. All in all Sri Lanka slouched back to the 1970s between 2005 and 2015.

The Yahapalanaya years did not succeed in fully undoing this damage. The first proper primary surplus in over half a century, a new Inland Revenue Act and a higher direct tax ratio are all landmark achievements, largely attributable to the late Mangala Samaraweera. This followed-on from the pivotal role he played in removing the EU fishing ban, regaining GSP+ and securing the MCC Compact as foreign minister. But all that was necessary was not politically feasible. A task made harder by the 2018 coup and the Easter bombings, which together put the economy into a tail-spin from which it is yet to emerge.

Then came the elections of 2019, 6.9 million voters handed over power to the adherents of Jathika Chinthana, N.M. Perea-Sirima economics and pocket-lining protectionism. Their confused, bastardised economic nirvana was trying to have the cake and eat the cake, while calling the cake kavun. It was a curious mixture of high modernism, superstition, naivety and envy. The equivalent of checking Gnakka’s latest oracles on an Apple watch while, in a most superior fashion, indolently supervising some oppressed fellow (generally in a caste, class or ethnic sense) tilling an organic paddy field to no avail. Complemented, of course, by an occasional Tweet decrying foreign conspiracies and calling for an import ban of all things foreign, posted from an iPhone ensconced in a homespun ‘Barefoot’ phone-case.

It was an economic policy that perfectly reflected the structure of their minds. And thus, the closed, controlled ‘license Raj’ marauded in all its heinous glory. As debt, hunger and unemployment slowly, then swiftly, ravaged the island, they stuck to the only thing they knew. Denial was their strategy. And this strategy – born of a paradoxical combination of insularity, insecurity, hubris and rank incompetence – unsurprisingly failed.

The final program

It is often said that countries, instead of learning from the mistakes of others, only learn from their own mistakes. Sri Lanka seems particularly pig-headed. We do not even learn from our mistakes. This time must be different. The question is how?

The IMF’s negotiating power is always greatest prior to a program, large in the early stages and wanes quickly as the economy stabilises. As a result, the stabilisation components of IMF programs – especially the components that increase revenue and reduce expenditure – tend to be implemented relatively successfully. However, in practice, the IMF kapuralas too are often incentivised to come to agreements fast. In negotiations the urgent need for assistance today, and the short-run political incentives of those in power, often trump tough negotiations to push-through reforms that will yield fruit for decades. The challenge is to entrench these reforms and undertake the longer-term structural changes that are the true catalysts of growth.

The themes of this final program need not be very different from the past six extended programs. But their sequencing needs to reverse. The structural reforms need to come first, as prior actions that are undertaken before a program is agreed on. This is especially true of reforms that are politically costly in the short-term but simple to implement. Politically costly reforms that require passing simple legislation – e.g. repeal of the Paddy Lands Act which prevents effective land use or transformation of the Railway Department into a SOE – are prime examples as they can be passed in a few weeks and don’t require complex drafting. As are laws where the complex work has already been done e.g. Monetary Law Act.

The second and third tranches can be allocated for politically costly and complex reforms that might take some time to formulate, such as fiscal rules or the creation of a competition authority. The imperative for front-loading reforms is particularly acute considering the expected political cycle, with elections scheduled for 2024. Therefore, the case for front-loading politically controversial reforms is especially strong in Sri Lanka today.

The authorities and Opposition must take inspiration from China; which used multilateral programs such as this as a commitment device to bind themselves. The spirit and tenor of negotiations must not be minimal, cosmetic compliance to get the next tranche of cash. It must be a comprehensive roadmap for economic breakthrough that is decisively implemented. The table below presents an example such a roadmap; a six tranche program that lasts over a 36-month period. Note that further details on these measures can be found in ‘A Crisis Manifesto’ and in ‘A Five Year Accelerated Economic Catch-Up Plan’.