Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 27 April 2021 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The World Bank released its Sri Lanka Development Update for 2021 in early April 2021. The theme of this year’s SLDU has been the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Sri Lanka’s economy and its poverty levels. Like the Central Bank Annual Report, it has covered the developments in all the major macroeconomic sectors in Sri Lanka in the recent past and how they would perform in the medium term

Central Bank: No doomsday event

Central Bank: No doomsday event

Around this time, my former colleagues at the Central Bank may be burning the midnight oils arguing among themselves how best they could present in the bank’s Annual Report for 2020 the success story of the present Government’s alternative economic policy strategy.

This is a policy which the bank’s Governor, Deshamanya Professor W.D. Lakshman, had been emphasising in his public appearances. He had even charged the critics of the Government as purveyors of doom and gloom without understanding the logic behind this policy stance.

This prompted me to examine how far he had been correct in his allegations in a previous article in this series (Available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/Critics-failing-to-understand-alternative-strategy-are-purveyors-of-doom-and-gloom-CB-Governor/4-713149). I argued in this article that, with all kinds of macroeconomic imbalances present, the economy had in fact been in doom and gloom. Hence, I recommended: “Thus, instead of dismissing the critics as purveyors of doom and gloom, it serves well for the Central Bank to sit back and listen to them.”

Since the bank’s Annual Report is yet to be released, there is no way for discerning whether the Central Bank has taken this advice seriously. However, an early indication in the form of a slide presentation released by the bank in March 2021 on ‘Sri Lankan Economy: Towards a New Era’ suggested that there was no doomsday event and it firmly believes that the economy was on a steady recovery path despite it being hit by a second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

World Bank’s Sri Lanka Development Update 2021: A purveyor of doomsday event?

Meanwhile, the World Bank released its Sri Lanka Development Update for 2021, abbreviated as SLDU-21, in early April 2021 (Available at: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/15b8de0edd4f39cc7a82b7aff8430576-0310062021/original/SriLanka-DevUpd-Apr9.pdf). On previous occasions, the World Bank had released this important document in a widely attended public event. But this year, due to practical difficulties associated with the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, it has been confined to a webinar to be conducted later this week.

The theme of this year’s SLDU has been the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Sri Lanka’s economy and its poverty levels. Like the Central Bank Annual Report, it has covered the developments in all the major macroeconomic sectors in Sri Lanka in the recent past and how they would perform in the medium term. In addition, as its main theme this year, it has looked at the crucial poverty levels in the country due to disruption of economic activities affecting mostly the self-employed after the country was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Central Bank’s linear growth projections in a non-linear world

The Central Bank in its slide presentation done in March had assumed a quick recovery for the pandemic hit economy. It had projected that the economy which contracted by 3.6% in 2020-a corollary of the first and second waves of the pandemic-would soon move towards a steady long-term growth path accelerating the growth rate to 6% in 2021.

Though the Central Bank has not presented the medium-term growth prospects for Sri Lanka, going by its method of macro-modelling done in the past, one can safely infer that it would be a linear growth in which growth in each successive year would be higher than that in the previous year. But the actual outcomes have always been different. Just to cite one example, in the Annual report for 2015, the bank had predicted a medium-term growth path of 5.8% for 2016, 6.3% for 2017, 7% for 2018, and again 7% for 2019. But the actual realisation had been 4.5% in 2016, 3.6% in 2017, 3.3% in 2018, and 2.3% in 2019. This type of linear projections in a non-linear world does not stand to the test of time. It is of course convenient for a researcher to ignore ‘the unexpected’ that might derail his projections of the future. But in complex macro-modelling there are tools available for a researcher to correct his baseline growth scenario by subjecting it to sensitivity analyses of changes in the contributing factors to economic growth.

Is it a quick V-shaped or a flattened U-shaped recovery?

The projected growth rate of 6% in 2021 by the Central Bank assumes a quick recovery of the pandemic affected economy to normalcy, known as a V-shaped recovery. This is based on the assumption of the continuation of the existing situation without being disturbed by unexpected events. However, I have argued in an article in this series earlier that the recovery will not be quick as projected by the Central Bank (available at: http://www.ft.lk/columns/C-19-economic-recovery-Most-probably-it-will-be-a-flattened-U-shaped-one/4-703372). At most, it would be a flattened U-shaped recovery due to many negative factors that have been introduced by the Government itself.

One is the costly tax concessions given to income and value-added taxpayers creating a dent of some Rs. 500 billion in the revenue base of the government in 2020 and in each of the subsequent few years. The other is the increase in the consumption expenditure of the government by offering job opportunities to unemployed graduates and the children of Samurdhi beneficiary families. Accordingly, I have predicted that the economic growth in 2020 and in next few years would be either negative or slightly positive. This would continue till year 2024.

World Bank: It is an elongated L-shaped recovery

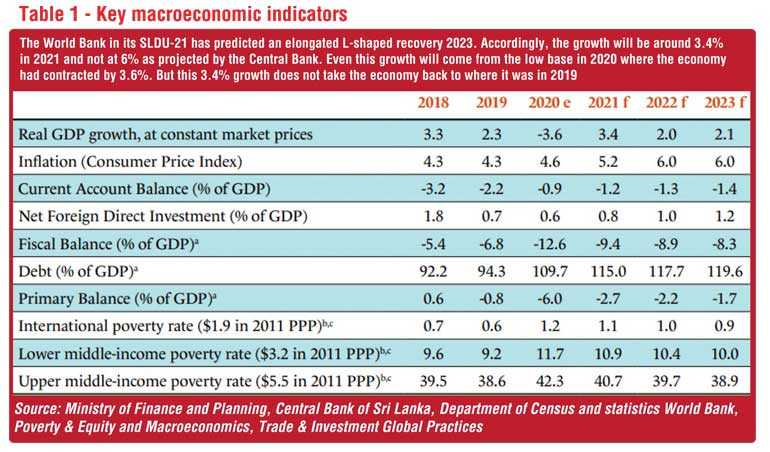

The World Bank in its SLDU-21 has predicted such a growth pattern till 2023 as shown in Table 1. Accordingly, the growth will be around 3.4% in 2021 and not at 6% as projected by the Central Bank. Even this growth will come from the low base in 2020 where the economy had contracted by 3.6%. But this 3.4% growth does not take the economy back to where it was in 2019.

This can be illustrated by a simple example. Suppose that Sri Lanka produces only one commodity, hoppers. If the country had produced 100 hoppers in 2019, the number of hoppers it had produced in 2020 would be 96.4. A projected growth of 3.4% in 2021 means the production of only 99.7 hoppers in that year. This is even below the number of hoppers produced in 2019. The World Bank has projected a growth rate of 2% in 2022 and 2.1% in 2023. In terms of the hopper analogy, 2022 would produce 101.7 hoppers. In 2023, it would be only 103.8 hoppers. Compared to the pre-COVID-19 pandemic production of 100 hoppers in 2019, this is only 3.8% hoppers more.

Clearly, according to the World Bank, return to normal economic growth will be only after 2024 based on the soundness of the economic policies to be adopted by the Government. If the economy does not return to normally even in 2024, it is not a flattened U-shaped recovery but the continuation of an elongated L-shaped growth pattern. What the Government should do is to take necessary policy measures to avoid this possibility.

Excessive money printing cannot be neutral on prices

The other macroeconomic numbers projected by the World Bank in its SLDU-21 too indicate a similar story. Though the World Bank has said that price inflation would rise gradually from 5.2% in 2021 to 6% by 2023, the money supply growth numbers so far warn us of an accelerated inflation in the future. When the economy has contracted by 3.6% in 2020, Central Bank’s broad money supply that includes 50% of the NRFC deposits as well-tagged M2b-has increased by 27% during the 14-month period from December 2019.

The release of such a massive quantum of money to the system should necessarily entail pressure for prices to increase. Normally when there is pressure for domestic prices to rise, a government could keep it under check by allowing import flows to the country. But Sri Lanka does not have foreign exchange cover to support such an increased import programme. In fact, foreign assets of the central bank and commercial taken together after adjusting for their foreign liabilities-known as net foreign assets-has been in the negative range during the recent few months. At the end of 2020, net foreign assets of the banking system were negative to the extent of Rs. 209 billion or $ 1 billion. By end-February 2021, this negative figure has increased to Rs. 386 billion or $ 1.9 billion.

With a slowed economic growth exacerbated by a lack of foreign reserves to increase imports, the domestic inflation should surely be higher than the projection of 6% by the World Bank. In this connection, the headline inflation as shown by the increases in the Colombo Consumers Price Index is misleading due to the wide range of price controls imposed by the government to relieve the public of high cost of living.

External sector is in a real doom

Macroeconomic projections made by the World Bank on the external sector in its SLDU-21 are also growth slowing rather than growth promoting. The Central Bank had projected a surplus in the current account of the balance of payments of about $ 500 million due mainly to a drastic cut in the trade deficit, a corollary of import restriction rather than an increase in the export of goods and services. In previous years, the trade deficit had been around $ 8 billion, but the bank had cut this to $ 4 billion in 2021. The ability of the country to reach this level will depend on how far it would be able to increase exports.

Given the present scenario of a third wave of COVID-19 pandemic with a new variety hitting the country, it is unlikely that the exports would be increased significantly. Taking this into account, the World Bank has projected a continued deficit in the current account of the balance of payments. As a percent of GDP, the current account deficit will rise from 0.9% in 2020 to 1.2% in 2021. This deficit will further rise to 1.3% in 2022 and 1.4% in 2023. Foreign Direct Investments or FDI are also projected to increase only marginally during this period. Accordingly, the net FDIs were at 0.6% of GDP in 2020. The World Bank has projected this to rise gradually but slowly during 2021 to 2023. Thus, in 2021, this would be 0.8% in 2021 and 1.2% in 2023. All these numbers are contrary to what the Central Bank has projected.

Rising debt profile need be correctly risk-assessed

An alarming picture has been created by the World Bank in its projections on the Government sector. One is relating to the ballooning of the country debt both domestic and foreign. The other is the ballooning of the overall budget deficit associated with an accelerated primary account deficit.

With regard to the foreign debt of the Central Government, the Central Bank had expressed satisfaction about the reduction of the foreign debt from 40% in 2020 to 35% in 2021 on one side and less reliance on foreign borrowings in the years to come due to enhanced foreign exchange earnings and increased investment inflows, on the other. However, when the foreign debt has fallen, the domestic debt of the Government, mainly from the banking sector has ballooned making the debt servicing a crucial issue for the already-clipped revenue base of the Government. The World Bank has taken a more cautious approach about debt in its SLDU-21.

Accordingly, debt to GDP ratio that stood at 94% in 2019 is expected to rise to 110% in 2020. This will continue to grow in the succeeding years, ending at 120% by 2023. If a proper risk assessment is made about the country’s rising debt profile, this is an alarming picture because the country has no sufficient foreign exchange to service the foreign debt and the government does not earn enough rupee funds to service its domestic debt.

Though the Central Bank had been continuously assuring foreign debt owners that the country will meet its all the debt obligations without failure on time, it has not gone into the heads of the foreign investors. This is evident from the deep discount at which Sri Lanka’s sovereign bonds are being traded in the secondary markets. All these bonds which were traded above the par value in February 2020 are now traded between $ 85 to $ 65 depending on the time to their maturity.

Money printing is like holding a tiger by tail

In the case of the domestic debt, there is a general feeling that a debt default event will not arise since the government can print money and service them at any time. This is the argument put forward by Modern Monetary Theorists-a breakaway group from the mainstream body of economists. They argue that talking about the evils of deficit financing is a myth because governments are not like individuals who may face debt repayment problems unless they have enough earnings. According to them, the governments can print money and meet their obligations.

The fallacy of this argument was presented by Adam Smith, father of modern economics, as far back as 1776 when he published his masterpiece, ‘The Wealth of Nations’. He said that history has shown that when governments do not earn enough revenue, either they declare themselves bankrupt or hide bankruptcy by pretended repayment by debasing the currency. Since bankruptcy of a state is not an event, it is the latter course that is being followed.

In the modern paper money era, a currency debasement is equal to printing more money to repay debt. But the production of excess money leads to inflation as well as depreciation of the exchange rate. Both are monsters waiting for the swallowing of an economy. Hence, borrowing from domestic markets thinking that it could be repaid by printing money is like holding a tiger by the tail. In the very first event the grip is loosened, the tiger will turn back and prey on the holder.

World Bank: Poverty numbers are critical

The Central Bank has assured in its slide show that improved macroeconomic resilience, supportive economic policies and reforms aiming at improving the doing business environment will help the country ‘to return to a high growth path in 2021 and beyond’. But the poverty numbers which the World Bank has predicted have vitiated this argument.

Sri Lanka is at present on the threshold of an upper middle-income country. The poverty benchmark for this category of countries is $ 5.50 per day per head in terms of 2011 purchasing power parity dollars. When applied this to actual data from the Census Department’s Household Income and Expenditure Survey or HIES data for 2016, the poverty level rises to 42% in 2020 and remain a little lower in each of the subsequent three years.

These numbers seriously question the quality of the growth being forecast by authorities. Hence, the World Bank recommends: “In the medium term, social safety nets could be better targeted toward the poor and vulnerable, while a system that allows support to be scaled up quickly and effectively in times of crises could be adopted. In the absence of a strong safety net, households tend to resort to negative coping mechanisms by drawing down savings, selling off assets, or reducing food intake. The lack of an appropriate safety net is highlighted in preliminary results from a World Bank COVID-19 rapid phone survey, which showed that about 44% of households did not have any source to help them cover emergency expenses.”

NM’s advice to Central Bank: Be dispassionate and free from political colours

These are serious issues to be addressed on a priority basis. The obligation of the Central Bank by the nation is to pinpoint them to authorities rather than praising their policies. This advice was given to the Central Bank in 1971 by the then Minister of Finance, Dr. N.M. Perera when he said that the Central Bank should come up with its advice dispassionately without the colour of any political party.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])