“I stopped smoking after being diagnosed with cancer. I was shocked when I heard about it. Doctors say it is because of tobacco smoking. I know it is late now to quit, but I decided to do so because I do not want my condition to worsen. It is heart-breaking to go to the cancer hospital in Maharagama and see what people are going through” – A 58-year-old farmer from Kilinochchi

By Sunimalee Madurawala

By Sunimalee Madurawala

These are the words of a 58-year-old farmer from Kilinochchi who started smoking in his youth while participating in a recent study conducted by IPS. It is a sobering reminder that while Sri Lanka has made notable strides in reducing the overall smoking rate from 38.1% to 28.4% between 2009 and 2018, smoking remains a significant health threat.

The challenge for Sri Lanka now is to identify the groups where smoking prevalence is highly concentrated – what we term the ‘Last Mile Smokers’ (LMS) – and implement policy measures that are specifically designed to reduce smoking among LMS.

The benefits of reducing the prevalence rates among LMS are substantial as tobacco smoking comes with high health, social, economic, and environmental costs. Tobacco consumption kills more than 20,000 Sri Lankans, annually. In 2016, tobacco smoking cost the Sri Lankan economy LKR 213.8 billion, equivalent to 1.6% of its GDP.

Against this backdrop, the IPS study identifies LMS categories, explores important dimensions of their smoking behaviour, and proposes a set of targeted policy measures that facilitate reaching them. This blog highlights some crucial findings and outlines policy responses to reduce smoking prevalence among the LMS.

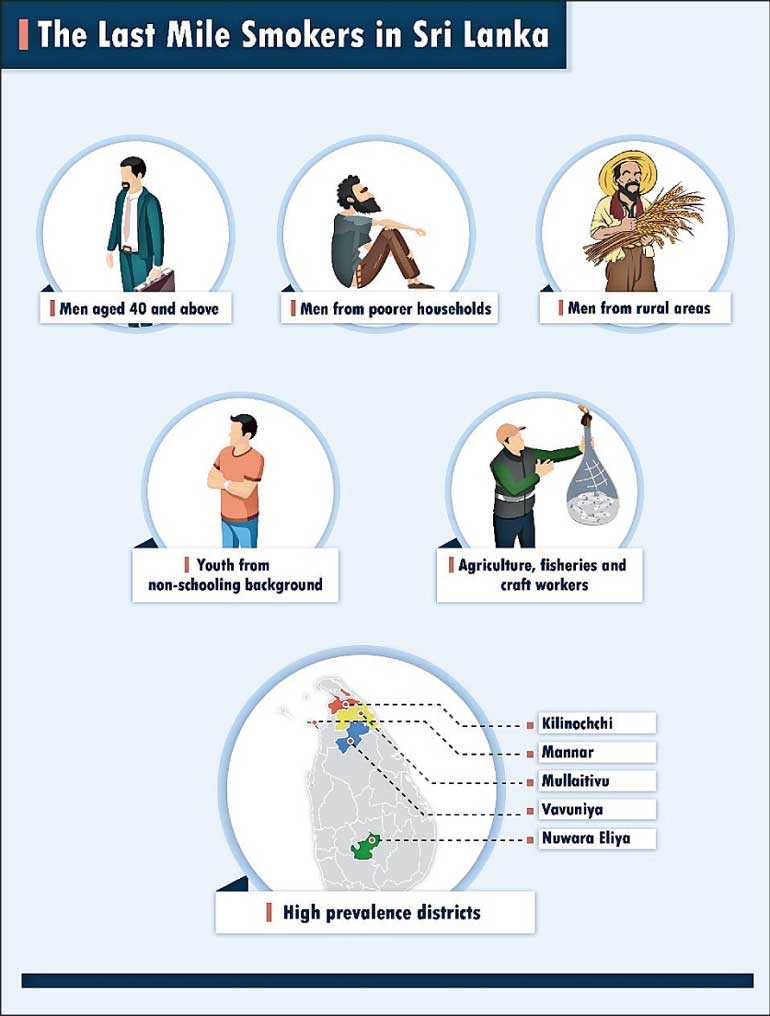

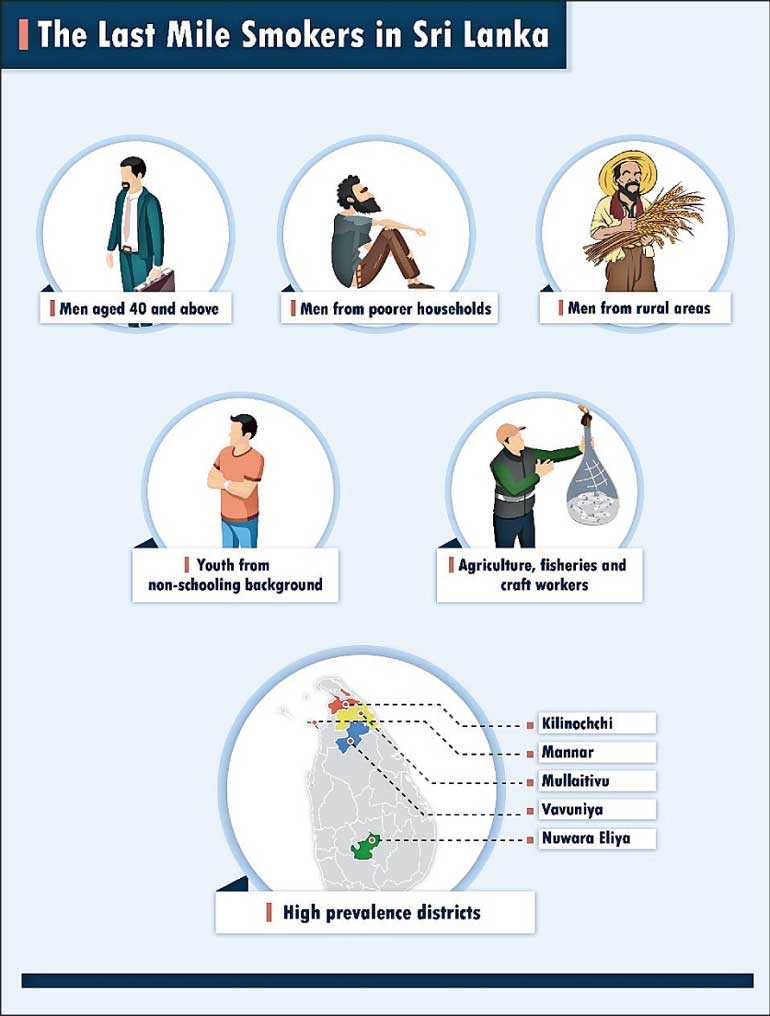

LMS in Sri Lanka – Secondary data reveals that the LMS tend to be older men (those in the 40 and above age category), from poorer backgrounds, and often living in rural areas. Young men from a non-schooling background also have high rates of smoking.

LMS in Sri Lanka – Secondary data reveals that the LMS tend to be older men (those in the 40 and above age category), from poorer backgrounds, and often living in rural areas. Young men from a non-schooling background also have high rates of smoking.

Persons occupied in ‘skilled agricultural and fishery workers’ and ‘craft and related workers’ occupational groups tend to smoke more. Further, Nuwara Eliya, Vavuniya, Mullaitivu, Mannar, and Kilinochchi districts recorded the highest percentage of detected smokers in 2016.

A series of discussions with different LMS groups across the country identified the following salient characteristics of LMS.

- Why do LMS smoke? Most smokers reported starting to smoke because they had perceived smoking as a remedy for loneliness and distress, were curious to experiment with new things, wanted to break the job monotony, were under peer pressure, and were stimulated by smokers in the family, community, and celebrities. Most of the smokers were initiated into smoking in their youth. They continued because it had become a habit or addiction, they perceived smoking as a remedy to overcome job monotony, lacked incentives and support channels to stop smoking, and lacked self-control to stop smoking.

- LMS want to quit smoking and support measures are needed to help them do so. The majority of smokers wanted to quit smoking and had tried to do so. Most of them had made at least one attempt to quit. Health concerns, financial reasons and commitments towards their families and children had motivated them to consider quitting.

- Almost all smokers from different sectors were aware of the adverse health and economic impacts of smoking. However, many LMS were unaware of its adverse impact on the environment, and the effects of second-hand smoking and third-hand smoking. Most of the smokers cited self-determination as the most crucial factor to quit smoking. Family and close network support is also important. Reaching for formal help in smoking cessation was minimal. This was mainly due to a lack of awareness on existing formal cessation channels and unavailability of such services targeted at LMS across the country.

“We have neither heard about cessation support nor have we participated in such programmes…There have been many instances where we wished that there was someone or some support that would encourage or motivate us to stop smoking. We like to stop, but we do not have access to such support programmes” – 42-year-old male tea estate worker from Hatton

- LMS are sensitive to price increases – Price plays a crucial role in shaping smoking patterns, both in relation to initiation and continuation. Overall, smoking has become less affordable in recent years according to the study participants. The responses by the LMS to price increases were: (1) reduce intake, (2) switch to cheaper brands/products, and (3) quit smoking. It should be added that only a few smokers from certain groups had considered switching to cheaper smoking products due to price increases.

- LMS purchase single sticks – With the price increase in recent times, many smokers have switched from buying an entire pack to single sticks. In fact, as many as 70 % of the LMS who participated in the study purchase single sticks.

How to reduce LMS numbers?

To continue reducing the prevalence of tobacco use, the Government needs to strengthen tobacco control policies and introduce targeted policy interventions that reach LMS categories.

- Continue price increases through tobacco taxation as a key policy intervention: Price increases in smoking products have forced some crucial changes in smoking behaviour that reduce the tobacco intake (e.g., to reduce the intensity of smoking and quit smoking). Hence, price increases must continue, and these should be inflation-adjusted and income growth-adjusted to make smoking products even less affordable.

- Ban sale of single sticks: Implementing the proposed ban on single stick cigarette sales in Sri Lanka without any further delay would contribute significantly to reduce smoking among the LMS.

- Respond to unmet demand for smoking cessation: There is substantial unmet demand for smoking cessation support, and emphasis should be placed on approaches that support smokers’ self-determination towards quitting smoking (e.g., “Stoptober” campaign in the UK).

- Introduce targeted interventions that reach the LMS: Tailor-made approaches are needed for wider outreach and to influence the LMS. This is important as LMS have specific needs and characteristics which are difficult to address through general interventions. Most of the LMS are from the informal sector, a sector that often goes unnoticed, is difficult to reach and not captured adequality by the existing health service networks. Integrating worksite tobacco control measures into other available health and safety programmes, using powerful pictorial messages and partnerships with high prevalence industries are some approaches proven to be successful in reaching the LMS. Sri Lanka can also adopt such interventions by appropriately re-designing them to the local context.

- Greater awareness creation: Awareness creation programmes and campaigns must be carried out more rigorously so that they reach the LMS. These should cover all aspects of adverse implications of tobacco smoking, including effects of second-hand and third-hand smoking.

Reducing smoking prevalence among the LMS would be beneficial for the public healthcare system and the entire economy yielding huge financial benefits and ensuring a labour force that is healthy, fit and productive. It would also make families happier and create a greener environment.

[This blog is based on IPS’ latest publication ‘Tobacco Smoking in Sri Lanka: Identifying and Understanding the Last Mile Smokers’. The study was funded by Cancer Research UK and field work was facilitated by the Alcohol and Drug Information Centre (ADIC).]

[Sunimalee Madurawala is a Research Economist at IPS. Her research interests include health economics, gender and population studies. Sunimalee holds a BA (Economics Special) with First Class Honours and a Masters in Economics (MEcon) from the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. (Talk to Sunimalee – [email protected]]

By Sunimalee Madurawala

By Sunimalee Madurawala

LMS in Sri Lanka – Secondary data reveals that the LMS tend to be older men (those in the 40 and above age category), from poorer backgrounds, and often living in rural areas. Young men from a non-schooling background also have high rates of smoking.

LMS in Sri Lanka – Secondary data reveals that the LMS tend to be older men (those in the 40 and above age category), from poorer backgrounds, and often living in rural areas. Young men from a non-schooling background also have high rates of smoking.