Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Tuesday, 1 June 2021 01:16 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

There is an impending danger that delaying corrective policy decisions might push Sri Lanka towards an L-shaped recovery, prolonging the pandemic-led recession indefinitely – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Sri Lanka’s economy contracted by 3.6% in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2020 in the aftermath of the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, recording the worst economic performance, as in the case of many countries. Industrial output declined by 6.9%, largely reflecting the adverse performance in apparel, manufacturing and construction. The services sector contracted by 1.5% due to the setback in tourism, transport and personal services. Agricultural production too fell by 2.4% in 2020.

Sri Lanka’s economy contracted by 3.6% in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2020 in the aftermath of the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, recording the worst economic performance, as in the case of many countries. Industrial output declined by 6.9%, largely reflecting the adverse performance in apparel, manufacturing and construction. The services sector contracted by 1.5% due to the setback in tourism, transport and personal services. Agricultural production too fell by 2.4% in 2020.

In an effort to revive the economy and to mitigate the adverse impact of the pandemic on individuals and businesses, the Government has implemented a series of measures including health allocations, cash transfers and tax postponements. These have been supplemented by the monetary easing policy adopted by the Central Bank since last year.

Despite such proactive measures, Sri Lanka is experiencing a prolonged economic recession due to the outbreak of the third wave of the pandemic. The economic recovery has become even more difficult due to the macroeconomic constraints faced by the country even before the pandemic. They include growth slowdown, high fiscal deficit, debt burden and balance of payments difficulties.

Alphabet of economic recovery

Questions have been raised across the world regarding the shape of the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic applicable to different countries; whether it is V-shaped, U-shaped, W-shaped or L-shaped.

The best-case scenario is the V-shaped recovery in which the economy rebounds quickly after a sharp decline. In a U-shaped recovery, it takes months or years to revive economic activity. In a W-shaped recovery, the economy recovers quickly but falls into a second recession. Hence, it is known as a double-dip recession.

The worst-case scenario is the L-shaped recovery in which the economy fails to recover in the foreseeable future.

Central Bank’s V-shaped projection unrealistic

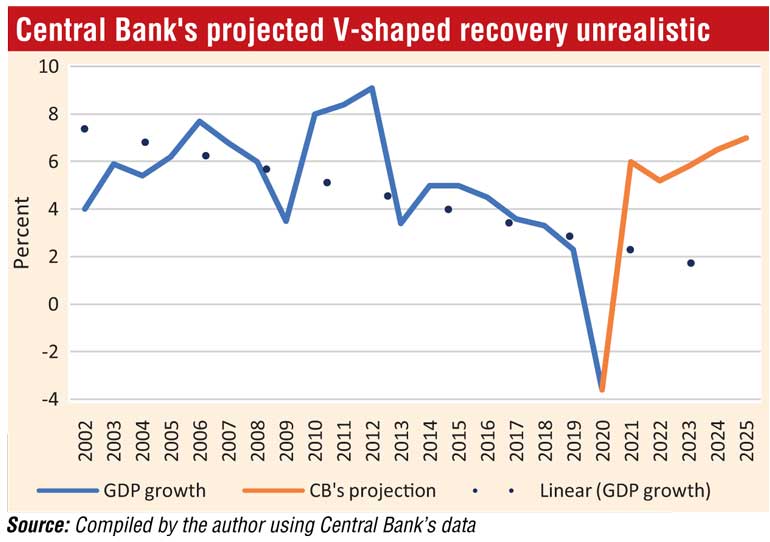

As per the medium-term macroeconomic outlook presented in the Central Bank’s Annual Report-2020, the Sri Lankan economy is expected to rebound strongly in 2021 and sustain the high growth momentum over the medium term, buoyed by growth-oriented policy support.

Accordingly, the economy is expected to achieve a V-shaped recovery with GDP growth jumping exorbitantly to 6.0% this year from the negative growth experienced last year, as shown in the chart. The growth momentum is projected to remain in the next five years accelerating the growth to 7.0% by 2025.

The Central Bank’s above projection seems to be over-optimistic, given the structural economic imbalances that have been prevailing in the country for a long time, leaving aside the adverse effects of the pandemic. This is clearly reflected by the fact that the economy was already on a downward path even before the pandemic.

GDP growth averaged only 3.7% during the ‘Yahapalana’ regime of 2015-2019. The average growth rate was down to mere 3.1% in 2017-2019, the period immediately preceding the pandemic.

Based on our time series projections as shown in the dotted line in the Chart, the annual GDP growth would not have been more than 2% from this year onwards, assuming there is no COVID-19 pandemic. The scenario appears even worse when a non-linear trend projection is applied, which indicates negative growth in the medium-term even without the pandemic.

Thus, Sri Lanka’s economic downturn is deeply rooted in factors beyond the pandemic which call for immediate policy action.

As the pandemic has exacerbated the economic slowdown, it is highly unrealistic to anticipate a V-shaped economic recovery overtaking the pre-pandemic growth, as projected by the Central Bank.

SL’s poor growth record

Following the cessation of the war in 2009, the economy followed a high growth path supported by the revival of production activities in the north and east together with post-war reconstruction and infrastructure development. However, that construction-based economic recovery was short-lived due to the lack of sustainable growth strategies, fiscal imbalances and export setback.

The weak economic performance has continued during the ‘Yahapalana’ regime during 2015-2019 in the absence of a coherent economic reform agenda aimed at export-led growth.

SL lacks technology-driven growth

Economic growth achieved thus far has been driven by using more factors of production – capital and labour. Such growth is identified as ‘factor-driven growth’. The economic slowdown immediately prior to the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that the economy could not grow any further solely depending on labour and capital inputs.

In other words, Sri Lanka has reached the ‘Production Possibility Frontier’ (PPF), in economic terminology. Raising the output beyond PPF requires application of technology and innovation thus enabling the economy to materialise ‘technology and innovation-driven growth’.

In the current global set up, technology and innovations based on human capital are the core growth drivers in many fast-growing countries, which have achieved the knowledge-economy status. Sri Lanka has been lagging behind in terms of knowledge economy indicators: economic and institutional status, education and skills development, Research and Development (R&D) and information and communication technology.

Unless appropriate policy measures are adopted to fill such gaps targeting technology and innovation-driven growth without further delay, it would be impossible to revive the country’s economic growth hampered by the pandemic in the near future.

Sri Lanka has lost numerous opportunities to achieve such growth in the post-liberalisation period mainly due to the politically-motivated decisions adopted by successive governments leaving aside economic priorities.

Import-dependent export growth

A country’s long-run growth rate is constrained by its export capacity and import demand, according to the well-tested theory introduced by Prof. Anthony Thirlwall of University of Kent in 1979. It is known as ‘Thirlwall’s Law of ‘Balance of Payments – constrained economic growth’. The larger the trade surplus (exports minus imports), the faster the economic growth.

In the long run, therefore, no country can grow faster than that rate consistent with balance of payments equilibrium on current account, unless it can continuously finance ever-growing deficits by foreign borrowing which, in general, is impossible, as evident from Sri Lanka’s experience.

The country’s envisaged economic recovery largely depends on its ability to raise exports. The pandemic-hit export sector showed some resilience in the first quarter of this year recording a 12.6% increase in total export earnings; industrial exports rose by 7.9%, and agricultural exports by 31.0%. Nevertheless, the trade deficit expanded in the first quarter due to a 12% increase in import outlays.

The Government has imposed import restrictions on a variety of goods since last year to ease the balance of payments difficulties. Given the high import content of domestic production, such restrictions have downside effects on the export sector as well as on overall economic growth. The recently-announced import ban on chemical fertiliser will adversely affect the agriculture sector, causing food security problems during the pandemic.

Thus, import controls are likely to prolong the pandemic-led recession, as per Thirlwall’s law.

Selective import relaxation for lawmakers

Whilst import restrictions on some of the essential goods consumed by ordinary people (including turmeric) are in force, the Cabinet is reported to have given its nod to permit importation of luxury vehicles for MPs, reflecting the Government’s absolute insensitivity to the country’s fiscal and foreign exchange crisis amidst the pandemic.

In contrast, New Zealand’s Prime Minister has said she and the ministers will offer a 20% pay cut lasting six months to show solidarity with those affected by the coronavirus outbreak, as the death toll continues to rise.

CB’s frequent tinkering with export proceed conversion rules

Last week, the Central Bank once again revised the rules on repatriation of export proceeds, requiring 25% of the proceeds to be converted within 30 days after receiving such proceeds.

The Monetary Board keeps its discretion to determine the specific export sectors or industries or individual exporters, who or which may be permitted to convert less than 25% of the total of the export proceeds received. This, however, will continue to be subject to not below 10% conversion of the export proceeds and received no later than 180 days from the date of shipment.

Such discretionary rules introduced in a bid to salvage the country’s foreign exchange situation have severe detrimental effects on the export sector hit by the pandemic, as reiterated in this column earlier.

Fiscal deficit and debt burden

A crucial macroeconomic imbalance that impinges on Sri Lanka’s growth recovery is the fiscal deficit and the accumulating debt service payments. The budget deficit rose to 11.1% of GDP in 2020 and the available indicators show even a higher increase in the deficit over 13% of GDP this year.

The continuation of the arbitrary tax cuts and the expenditure hikes already worsened the fiscal situation requiring frequent borrowings from domestic and foreign sources. Annual debt service payments amounting to around 150% of the Government revenue exert enormous pressure on budgetary management.

While the Central Bank’s low interest rate policy helps to ease the domestic debt service burden, the depreciation of the rupee in recent weeks makes external debt service payments extremely

costly.

Overdependence on foreign loans and swaps

Instead of pursuing the Government to stick to a fiscal consolidation programme targeting a lower fiscal deficit so as to ease the debt burden, the Central Bank continues to rely on short-term foreign borrowings and swap arrangements. This is in addition to its accommodative monetary policy stance with regard to Government’s domestic borrowings.

Last week, the Bangladesh Bank has agreed to provide a swap facility of $ 200 million. Sri Lanka received renminbi-denominated swap of $ 1.5 billion from China last month. In addition, the Republic of Korea last month agreed to provide concessional loans amounting to $ 500 million to finance the identified projects.

More swap facilities are in the pipeline, according to the Finance Ministry sources, as reported in the media.

Fresh debt-funded infrastructure projects

Meanwhile, the Government is reported to have launched several major debt-funded infrastructure projects including highways a few days ago amidst the pandemic and severe external debt problems. Such borrowings will certainly aggravate the country’s staggering macroeconomic imbalances.

U- or L-shaped recovery for Sri Lanka?

In the backdrop of Sri Lanka’s growth slowdown even prior to the pandemic, the V-shaped recovery projected by the Central Bank is far from reality.

Assuming a best possible scenario, hopefully the economy would revive after two to three years characterised by U-shaped recovery. The bottom of the U shape represents the extended period of the recession before recovery.

A longer post-pandemic U-shaped recovery implies that the economy will take a number of years for recovery. First and foremost, the length of the economic recession depends on how long it takes to eradicate the coronavirus at the national and global levels.

Proactive policies are essential to correct the macroeconomic imbalances, specifically the fiscal deficit, bad debt dynamics and the balance of payments deficit so as to revive the Sri Lankan economy at least with U-shape recovery, which is considered to be the second-best option below V-shape recovery.

There is an impending danger that delaying corrective policy decisions might push Sri Lanka towards an L-shaped recovery, prolonging the pandemic-led recession indefinitely.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka. He is former Director of Statistics, Central Bank of Sri Lanka and reachable via [email protected])