Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Monday, 12 February 2024 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The value of the rupee will have to be at least partially restored if the country is to avoid stagnation and another currency crisis further down the road

One of the important issues that appears to have gone under the radar since the debt crisis of April 2022 is the overvaluation of the Sri Lankan rupee. This is in spite of the fact that many commentators argued that the overvaluation of the Sri Lankan rupee was an important contributor to the debt crisis (see CBSL, 2023; Athukorale and Wagle, 2023). To the extent that they pay any attention at all to the exchange rate, they argue that the sharp depreciation of the currency following the foreign debt default in April 2022 restored the competitiveness of the currency such that its value is presently “supportive of the country’s trade competitiveness” (CBSL, 2023, p. 194).

One of the important issues that appears to have gone under the radar since the debt crisis of April 2022 is the overvaluation of the Sri Lankan rupee. This is in spite of the fact that many commentators argued that the overvaluation of the Sri Lankan rupee was an important contributor to the debt crisis (see CBSL, 2023; Athukorale and Wagle, 2023). To the extent that they pay any attention at all to the exchange rate, they argue that the sharp depreciation of the currency following the foreign debt default in April 2022 restored the competitiveness of the currency such that its value is presently “supportive of the country’s trade competitiveness” (CBSL, 2023, p. 194).

Those arguing that the Sri Lankan rupee is not overvalued typically point to the recovery in the current account of the balance of payments and, perhaps more importantly, the fall in the real exchange rate. We argue in what follows that while the sharp depreciation of the rupee in April 2022 restored its competitiveness for a brief period the Sri Lankan rupee is currently more overvalued than it was at the outbreak of the crisis.

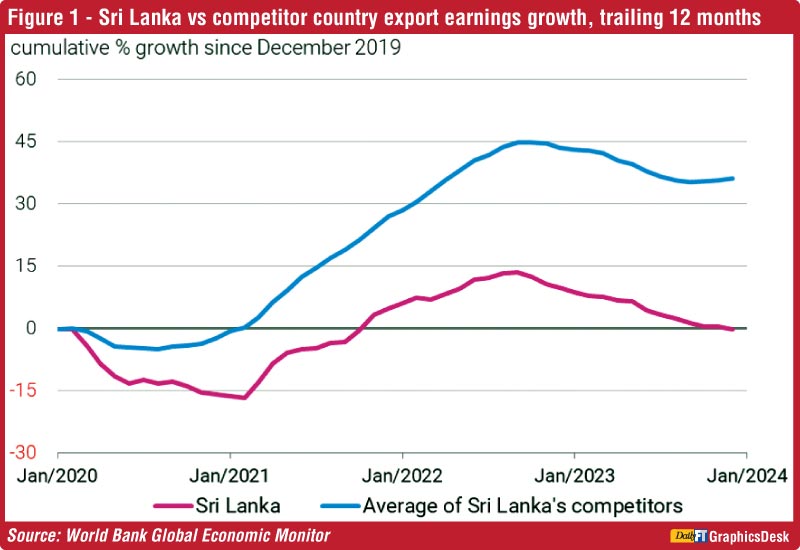

There was most certainly a recovery in the current account following the sharp depreciation of the exchange rate, but this recovery cannot be attributed to any alleged impact the depreciation supposedly had on export growth. Specifically, the recovery of the current account is largely attributable to a post-crisis recovery in tourism and private remittances, and to a lesser extent a fall in the trade deficit. The latter has been in no small measure thanks to lingering import controls (to which the Government said it was opposed) and deferred interest payments. What is clear is that this recovery has not been underpinned by a recovery in export earnings. Figure 1 depicts Sri Lanka’s growth in export earnings in relation to that of competitor countries. It may be observed that while Sri Lanka’s export earnings have risen along with those of its competitors, the growth has been relatively anaemic.

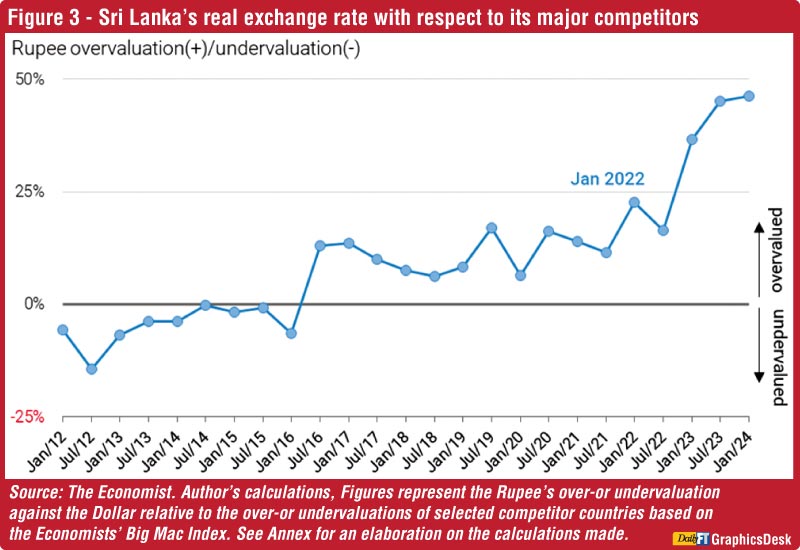

The second alleged indicator of the competitiveness of the currency is argued to be the real exchange rate, or more precisely the real effective exchange rate (REER, see endnote 1). In its December 2023 Monthly Indicators Report the CBSL shows the REER falling sharply below the 100 level (the level that indicates neutral competitiveness) in the post-crisis period, and remaining there even after a significant bounce as a result of an appreciation in the nominal value of the rupee. That is to say, the chart shows the competitiveness of the rupee improved as a result of its unprecedented depreciation, and continued to be competitive even after its subsequent appreciation. The CBSL’s 24-country composite REER is shown in figure 2 alongside the RER with respect to the US alone. It shows that the CBSL’s 24 country REER moves closely with the US REER suggesting that the latter dominates the movement of the former.

Bizarrely, and contrary to what has been argued by many, including the current Governor of the CBSL, the CBSL’s REER computations suggest that the Sri Lankan rupee was not overvalued prior to the crisis when compared to 2018, even after the appreciation of the REER in late 2021 and early 2022 (see endnote 2) That is to say, these computations belie the claim that the overvaluation of the Sri Lankan rupee was an important contributory factor of the debt default.

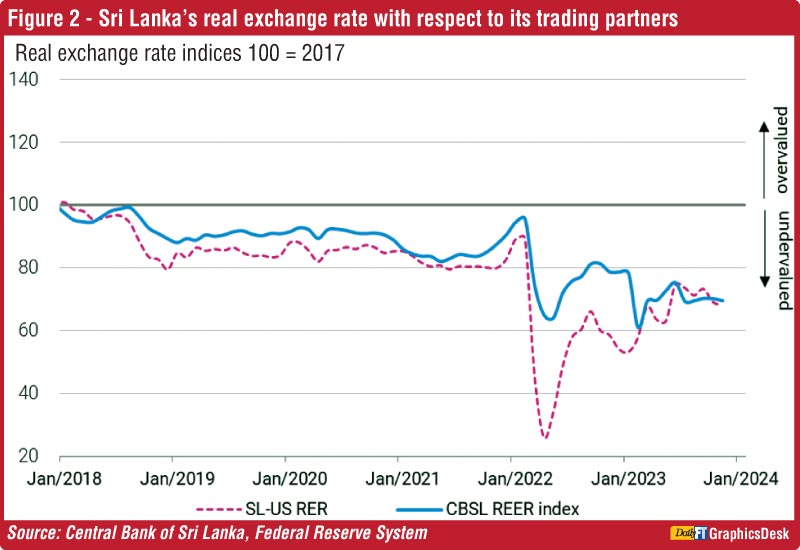

What should be apparent from the preceding is that the CBSL’s computation of Sri Lanka’s REER with respect to its major trading partners is a misleading indication of the competitiveness of the rupee. This is because it suggests that Sri Lanka’s major competitors in its export markets are its trading partners—the countries to which it is exporting. In fact, Sri Lanka’s competitors are those countries that are also exporting the same goods as those exported by Sri Lanka to these markets. This means that the REER that needs to be computed as an indicator of the competitiveness of the Sri Lankan rupee is one that reflects its competitiveness with respect to the currencies of its competitors in these markets.

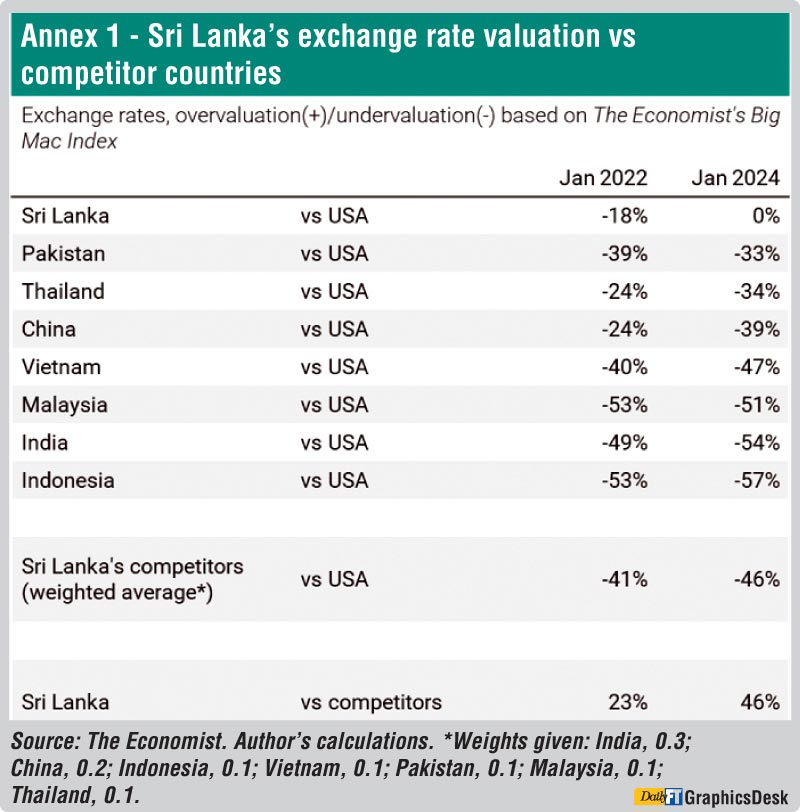

Figure 3 is a plot of this REER. The competitor countries chosen are India, Pakistan, Thailand, China, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia (see endnote 3). It shows that the Sri Lankan rupee has become increasingly less competitive, i.e., increasingly overvalued with respect to the currencies of its competitors. Indeed, the Sri Lankan rupee is currently more overvalued with respect to the currencies of these other countries than it was just prior to the debt crisis and the resulting collapse of the value of the rupee. It warrants noting that the rupee is now more than 30% overvalued with respect to the currencies of Pakistan and Thailand and 50% more overvalued than the Indian rupee as compared with its pre-crisis value (see Annex 1). The overvaluation of the Sri Lankan rupee with respect to the currencies of these three countries has been highlighted because they are countries with which Sri Lanka has signed bilateral agreements preventing the Government from using countervailing trade measures to compensate for this overvaluation.

The preceding is not intended as arguing that there should be an immediate depreciation of the Sri Lankan rupee to restore its competitiveness. In fact, given the weakened state of the export sector, particularly manufacturing, the required currency adjustment may only bring about more pain, particularly given the foreign debt overhang and considerable dependence on imports, especially food imports. The problem in this regard is the absence of anything resembling a developed manufacturing base that could take advantage of such a realignment of the rupee exchange rate. Indeed, the consequence of such a realignment in the context of the absence of a manufacturing base may even be a protracted period of stagflation. Like death and taxes, one more thing is certain. The value of the rupee will have to be at least partially restored if the country is to avoid stagnation and another currency crisis further down the road. But for a low-middle income country that has long enjoyed the direct consumption benefits of an overvalued exchange rate such a restoration will prove politically and economically difficult. The likelihood is that political considerations – the impending Presidential elections – will once again delay the required adjustments, with politicians using REER computations to justify this delay. Of course, the longer the delay the more difficult the necessary adjustment.

References:

Athukorale, P. and S. Wagle (2022) The Sovereign Debt Crisis in Sri Lanka: Causes, Policy Response and Prospects. New York: UNDP.

CBSL (2023) The Central Bank of Sri Lanka Annual Report 2022. Colombo: Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

Endnotes:

1. The REER is a weighted average of a country’s currency in relation to an index or basket of other major currencies. These weights are determined by comparing the relative trade balance of a country’s currency against that of each country in the index. A fall in the REER indicates an increase in the competitiveness of the currency while a rise indicates a fall in its competitiveness.

2. This also suggests that the widely heard allegation that the Central Bank was at fault for not allowing the currency to depreciate during the period between December 2019 and September 2021 was baseless, given that the CBSL’s own data show that the rupee was, at the time, if anything, undervalued.

3. The weights assigned are 0.3 for India, 0.2 for China and 0.1 for the others. Bangladesh has been omitted from this list due to missing data.

(Bram Nicholas is the COO of the research and training company ETIS Lanka.

Howard Nicholas is a retired associate professor in economics, Institute of Social Studies (The Netherlands).)