Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 5 May 2020 00:06 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lankan industries are still unable to meet their skills requirements. Even though Sri Lanka is currently struggling to overcome high levels of unemployment, some employers in some sectors are reporting skill shortages.

Sri Lankan enterprises are expected to face a growing number of hard-to-fill vacancies due to skills shortage in most economies. Shortages, unemployment and skill mismatch have negative financial and non-monetary consequences for employers, individuals, and society as a whole. It is vital that not only is the Government able to remedy this situation, but also that private sector skilled training institutions should take collaborative actions on it.

Many unemployed young people in our country are struggling to find job, but the common obstacle we see here is the lack of skills requested by industries. Therefore, the article highlights that the creation of a skilled workforce in the future will be the catalyst for the country’s rapid growth.

The world doesn’t remain the same every day. It keeps on changing. Every day, we come across new developments which may be technological, process improvements, newer ideas, products and so on and thus business environment is facing considerable changes (Heraty, 1999).

The day-to-day new technological changes demand new talented/skilled employees in this new era. The continuous shortage of those skilled workers remains a weakness to our human capital development. Therefore, if we are to make our human prosperous, we need to start new strategies for skills development programs in our country to meet the talent requirements of industries.

Labour force participation in Sri Lanka has historically been low with only about a half of the eligible people between the ages of 15 and above offering their services to the market. While the male participation has been around 72%, the female participation has been low at about 35%. Of them, the youth consisting of those between the ages of 25 and 40 have been the largest segment in the labour force, making up of almost the entirety of the people in that age group. Hence, if they leave the country, it is considered a severe loss to the economy (W.J. Wijewardana, 13 May 2019).

Introduction

“Human capital” is becoming a major term in development sectors. The quality of human capital determines the productivity and, ultimately, the growth and development of enterprises. Human capital—defined as the “stock of economically productive human capabilities”1 — encompasses knowledge, health, skills, entrepreneurial talent, determination and other human traits that lead to success in endeavours.

Human capital is obtained through general education and is transferable from one enterprise/endeavour to another. Skills are a subset of human capital specific to a particular task, job or enterprise and are obtained through specialised education or training, such as carpentry or dentistry. Human capital and skills may play different but complementary roles in the growth and development of the private sector. General human capital may be used to generate ideas, form a company, and develop new products. Skills, however, are required to produce the product/service at competitive prices.

This article examines the importance of human capital and strategies of skills development for development of Sri Lanka. It focuses on graduates and institutions in tertiary education, and whether these institutions are responsive to changes in knowledge, labour markets, and economic development. Knowledge and skills are central not only to make labour and capital more productive, but also to technical progress-the major source of private sector development and sustained growth.

It also examines why the private sector suffers from skill shortages when unemployment is high among graduates, and the policies that can successfully address Sri Lanka’s skills gap. It concludes that in the short run, human capital development should focus on providing short, practical courses to secondary and higher education graduates involving primarily on-the-job training. In the long run, there is a need to change the way students are trained, including curriculum reforms that favour science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Emphasis should also be placed on critical thinking, problem solving, discovery, and experiential pedagogy rather than rote learning.

Current status of human capital and skills in Sri Lanka

Challenges in education

Annually about 150,000 adolescents and youth join the labour force with low skills or no skills at all, which is the biggest challenge in Sri Lanka. With this background, in South Asia, Sri Lanka has the highest literacy rate, yet it is unable to develop the fundamentals to create a sustainable and a progressive education system.

Sri Lanka is also unable to retain the best brains – brain drain is a huge issue for its development and growth. With thousands of unregulated international schools across the country parents are forced to send their children for the simple reason that the political establishments are only interested in short-term policies and the inability to think for the future and create a future ready society.

Furthermore the fundamental issues in the Sri Lankan public education system can be cited as access to quality education, dearth of trained teachers across the country (trained teachers are usually provided mostly to elite schools), lack of Government funding for education, no future focus, serving their own political interest, and an unregulated education system.

Sri Lanka’s public investment in education is much less than the average of 4% spent by lower middle income countries. Since the public sector is the main provider of university education in Sri Lanka, the limited public resources for tertiary education is a main constraint for expanding opportunities for university education in the country.

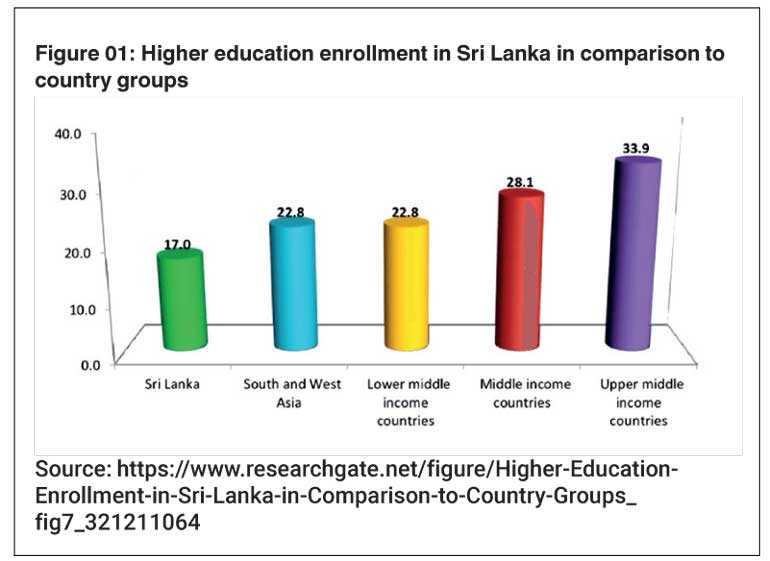

Higher education enrolment in Sri Lanka in comparison to country groups

Sri Lanka’s university admission process is highly competitive where the students are ranked and admitted in accordance with a standardised scoring system based on the A-Level examination results. Figure 01 emphasises comparatively very low of gross enrolment ratio at tertiary level 17%, 24,198 (16.7%) out of 144,816 who qualified for State university entrance.

Main challenges of the education system are lack of quality, attractive and relevance to job market. Each year, more than 100,000 qualified students are forced to abandon their ambition to enter a university. Compared to other developing countries, the number of students enrolled in tertiary education is extremely low in Sri Lanka.

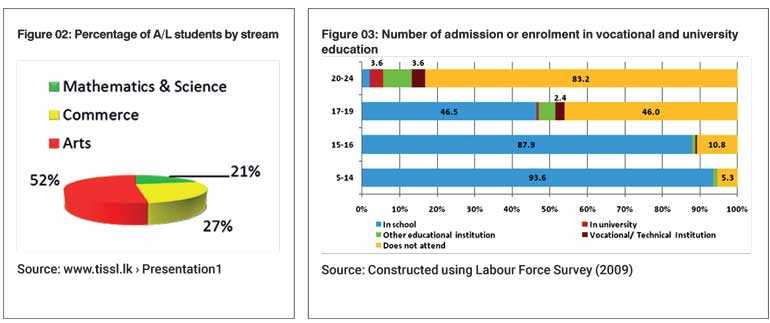

Generally there is a view that universities do not have the appropriate and updated education system for students to meet the requirement of the labour market. Figure 02 indicates that students are more in the arts stream (52%) and only 21% are in the mathematics and science stream. The other streams have more demand yet the number of enrolments is comparatively very low.

Tertiary education enrolment

Sri Lanka needs to rapidly increase the availability of good quality and technical skills in the labour force. The Government is aware that the country faces serious constraints in skills development, which jeopardises its goal of promoting a globally competitive industry. However, this is not the case for vocational and technical skills.

The key challenge in the tertiary education that there is a mismatch in the courses offered by higher education institutes and competencies needed by the private sector. Major reasons for this mismatch are the outdated curricula and the lack of interaction with the private sector when designing degree programmes.

Figure 03 highlights that admissions or enrolments in vocational and university education is very low among 17 to 24 years old. Enrolment in vocational/technical institutes is only 2.4% among 17 to 19 year olds, which shows a setback in a talent supply for the industries. Also among the same group, about 46% do not attend any education or training programmes.

Demand for job-specific skills is growing in Sri Lanka, which intends to become a more competitive, middle-income country (MIC). As its economy has grown, the composition of its gross domestic product (GDP) has begun moving from agriculture to higher-value-added industry and services, where jobs as machine operators, technicians, craftspeople, sales personnel, professionals, and managers require specialised training.

The Sri Lankan Government recognises the need to increase the employability rates of youth, a group that experienced an unemployment rate of 20.6% in 2015. (For comparison’s sake, only about 4% of the general population, including youth, was unemployed in 2015.) To that end, two ministries – the Ministry of Skills Development and Vocational Training and Ministry of Youth Affairs – are tasked with providing technical and vocational training to prepare youth and young adults for careers in a wide range of occupational fields. (Specific fields, oversight authorities, and requirements are discussed below.)

To design a responsive reform agenda, policy makers need to thoroughly understand both demand-side pressures for skills and constraints on skills supply.

Tertiary education

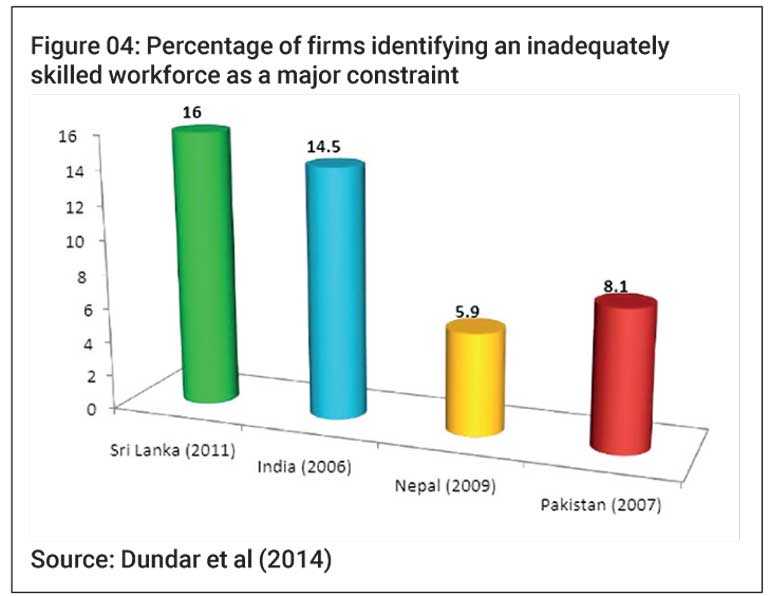

More firms in Sri Lanka identify a shortage of vocational and technical skills as a major constraint than firms in India, Pakistan and Nepal (Figure 04). This scarcity is exacerbated by the fact that many well-qualified skilled individuals migrate overseas for employment, although migration does provide a substantial source of remittance earning. (Harsha Aturupane and Mari Shojo, 2016)

Way forward

Conclusion

Higher technical and vocational skills enhance the competitiveness of economies and contribute to social inclusion, decent employment and poverty reduction. They can open doors to economically and socially rewarding jobs and support the development of informal businesses. These skills can also promote the re-insertion of displaced workers and migrants, and assist the transition to work for school drop-outs and graduates. Developing job-related competencies among the poor, the youth, and the vulnerable that are relevant to the private sector will contribute to inclusive growth and poverty reduction on the continent.

Finally, the country’s prosperity depends on how many of its people are in work and how productive they are, which in turn rests on the skills they have and how effectively those skills are used. Skills are the foundation of decent work. The cornerstones of a policy framework for developing a suitably skilled workforce are: broad availability of good-quality education as a foundation for future training; a close matching of skills supply to the needs of enterprises and labour markets; enabling workers and enterprises to adjust to changes in technology and markets; and anticipating and preparing for the skills needs of the future.

Footnotes

McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Economics 1993.

References

(The writer is Assistant Director, NHRDC)