Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Tuesday, 21 December 2021 03:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Government obtained as much as Rs. 1,658 billion of net credit from the Central Bank and commercial banks during the last 12 months. This reflects the extent to which liquidity is injected into the market by way of bank lending to the Government

The annual inflation rate has reached the double-digit mark for the first time after a lapse of 12 years, aggravating Sri Lanka’s multipronged economic crisis. The economy is already hit by external debt servicing problems, low inward remittances and tourist earnings, foreign exchange shortage, consumer goods scarcities, low savings and investment, and production downfall.

The annual inflation rate has reached the double-digit mark for the first time after a lapse of 12 years, aggravating Sri Lanka’s multipronged economic crisis. The economy is already hit by external debt servicing problems, low inward remittances and tourist earnings, foreign exchange shortage, consumer goods scarcities, low savings and investment, and production downfall.

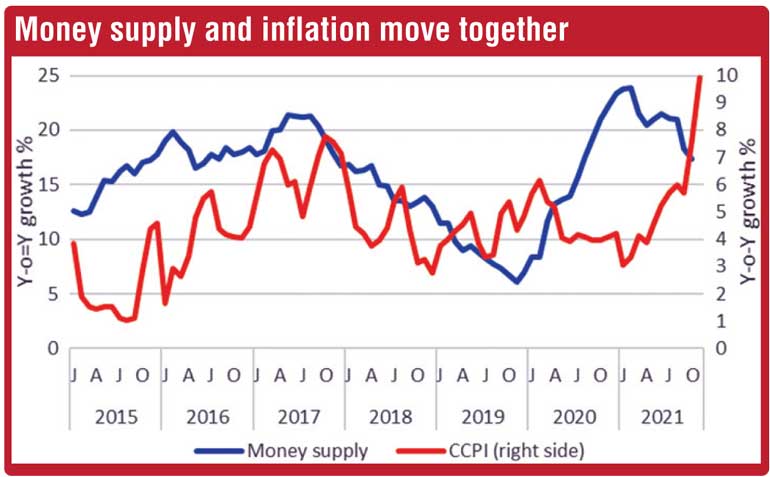

While supply shortages, high production costs, rupee depreciation and increased import prices have had cost-push effects on inflation, the profound demand-pull impact stemming from the rapid money supply growth on inflation cannot be underestimated. The money supply rose by a whopping 42% during the last two years from Rs. 7,456 billion in October 2019 to Rs. 10,582 billion in October 2021.

The easy monetary policy adopted by the Central Bank authorities following the obscured Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) since the beginning of last year is the single most prominent factor that has led to the unprecedented increase in money supply, and in turn, high inflation.

In contrast to the position maintained by the Central Bank authorities on the neutral effect of the money supply growth on inflation, the imminent inflationary pressures on the horizon were projected in this column several months ago (https://www.ft.lk/columns/Inflationary-pressures-on-the-horizon/4-712891).

Money supply growth

The broad money supply (M2), defined as the narrow money supply (currency and demand deposits) plus time and savings deposits held by the public with commercial banks rose by 17% over the last 12 months. This was due to a 23% increase in the net domestic assets of the banking system mainly caused by the rise in Net Credit to the Government (NCG).

The increase in the money supply was largely an outcome of the rise in NCG by 38%; NCG disbursed by the Central Bank and commercial banks rose by 156% and 15%, respectively.

The Government obtained as much as Rs. 1,658 billion of net credit from the Central Bank and commercial banks during the last 12 months. This reflects the extent to which liquidity is injected into the market by way of bank lending to the Government.

Central Bank loses grip on the money supply

As stipulated in the Monetary Law Act, the Central Bank is directly responsible for maintaining price stability, which is a prerequisite to macroeconomic economic stability. The policy instruments available to the Central Bank for the purpose include open market operations (OMO, i.e., buying and selling Treasury bills and bonds), policy interest rates, Statutory Reserve Ratio (SRR), officially announced exchange rate, and foreign exchange trading.

As the Central Bank is continuing to lend to the Treasury to finance its cash shortfalls as pointed out above, the monetary policy is severely constrained by fiscal deficits reflecting fiscal dominance over monetary policy. As a result, the Central Bank is not in a position to mop up any excess liquidity through OMO by selling Treasury Bills to the market. This has resulted in a steep rise in the monetary base, and currency issues (notes and coins) causing a rise in the money supply. The Central Bank has also been cautious in making upward adjustments in policy interest rates to contain market liquidity due to debt commitment implications of interest rate hikes.

As regards the exchange rate too, the Central Bank has opted to maintain an unrealistic fixed exchange rate to avert possible adverse effects of rupee depreciation on inflation and foreign debt commitments.

Thus, the Central Bank has lost its grip on its key policy instruments – interest rate and exchange rate. In the absence of those two policy instruments, an open economy cannot sustain, as articulated in the well-tested Mundell-Fleming model.

Impact of money supply on inflation undeniable

The Central Bank authorities have been denying to accept the well-established relationship between the money supply and inflation which is based on Monetarism founded by the world-renowned economist, Milton Friedman.

Contrary to the beliefs of the monetary authorities, there is a close relationship between the money supply growth and inflation in Sri Lanka, as depicted in the Chart. The year-on-year inflation, measured in terms of the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI) rose to 9.9% in November 2021, almost reaching the double-digit mark for the first time since 2009.

The steep increase in the money supply resulted in a rise in market liquidity relatively to slow GDP growth. This has led to the situation that economists describe as “too much money chasing too few goods”. Going against mainstream Economics, the Central Bank authorities are not willing to accept this cardinal principle.

The inflationary pressures of the money supply clearly reflect the pitfalls of the so-called Modern Monetary Theory-styled monetary policy adopted by the Central Bank since early last year to accommodate the budgetary needs of the Government by directly purchasing Treasury bills and bonds, as I argued in a previous FT column (http://www.ft.lk/columns/Money-printing-to-repay-Govt-debt-worshipping-MMT-is-likely-to-magnify-economic-instability/4-710612).

Inflation targeting monetary policy

Since the 1980s the Central Bank had conducted monetary policy with a targeted monetary aggregate. Globally, monetary targeting was found to be problematic due to the instability between monetary aggregates and goal variables such as inflation. Hence, the monetary targeting frameworks have been downplayed or abandoned in several countries.

A number of monetary authorities across the world have begun to use inflation targeting for the conduct of monetary policy following the success in New Zealand which launched inflation targeting in 1990. In terms of such policy framework, the central bank assumes the responsibility of maintaining a pre-announced inflation target using a monetary policy tool such as interest rate. In this case, the concerned central bank is totally accountable to keep inflation within the target. The success of inflation targeting, however, depends on several factors, particularly fiscal discipline aiming at a low budget deficit.

In Sri Lanka, initiatives were taken four years ago to introduce the inflation targeting monetary policy framework under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) with the IMF during 2016-2019. According, the Central Bank was to embark upon a monetary policy framework with an inflation target of 4-6% envisaging a decline in the budget deficit to 3.5% of GDP by 2020. However, this was never materialised, as the present Government abandoned the EFF in late 2019.

Such inflation targeting monetary policy framework could have strengthened the capacity of the Central Bank to operate its monetary policy prudently freeing itself from the political pressures to accommodate fiscal needs.

Arguments against inflation targeting baseless

India adopted inflation targeting regime in 2016 under a new monetary policy framework. Arguing against such policy, Surjit S. Bhalla, Executive Director of the IMF who is representing India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Bhutan claims that inflation targeting in India has contributed to a decline in GDP growth rather than to contain inflation (https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/inflation-rbi-monetary-policy-indian-economy-7236363).

He states, “Countries which have not adopted inflation targeting reveal lower inflation than those that did. There are also costs to inflation targeting in India. It led to higher real policy rates, in the mistaken belief that high policy rates affect the price of food, oil, or anything else. But high real rates affect economic growth, by affecting the cost of domestic capital in this ultra-competitive world”.

He further asserts that the decline in inflation rates across the world over the last couple of decades owing to globalisation, demographics and unlimited supply of skilled labour coincided with the introduction of inflation targeting regimes by central banks. Hence, the inflation decline cannot be attributed to inflation targeting, according to Bhalla. He concludes with the remark, “present reality of no country for inflation targeting”.

Bhalla’s pessimistic view on inflation targeting is misleading, as his study is not based on any sound theoretical or empirical footing. His findings are exclusively based on some oversimplified comparisons of median inflation rates of inflation targeting vis-à-vis non-inflation targeting regimes in emerging markets and advanced economies during the period 1990-2019.

The conclusions of Bhalla’s study are not substantiated with any robust econometric tools such as the Granger Causality Test to ascertain the impact of inflation targeting on each country’s general price level using the relevant macroeconomic variables including fiscal deficit, money supply and central bank lending to the government.

Therefore, Bhalla’s conclusion, “There is precious little evidence – for India or rest of the world – that inflation targeting works or has worked” is unacceptable.

Independent central banking with inflation targeting needed for Sri Lanka

It is recognised across the globe that the central banks which are more independent perform better in achieving their main objective – price stability. The reason is that the central banks that are under the direct influence of the government, as in the case of Sri Lanka, are compelled to bridge the unfinanced portion of the budget deficit by using their discretionary monopoly power of creating ‘fiat money’ to lend to the government.

The revenue generation by the government through such money creation, known as ‘seigniorage’, increases the central bank’s monetary base which brings about a multiple expansion of the aggregate money supply causing inflation. This is exactly what has happened in Sri Lanka since last year due to the ill-advised monetary policy formulation which has led to accelerate inflation to the double-digit mark.

In order to insulate monetary management from such inflation-biased political pressures, central bank independence becomes crucial. As the initiatives taken in Sri Lanka a few years ago to devise an independent monetary authority by the now abandoned Central Bank Bill along with strict fiscal discipline, prudent monetary policy aiming at inflation targeting seems a distant reality.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor of Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka and a former Central Banker, reachable at [email protected])