Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 25 February 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

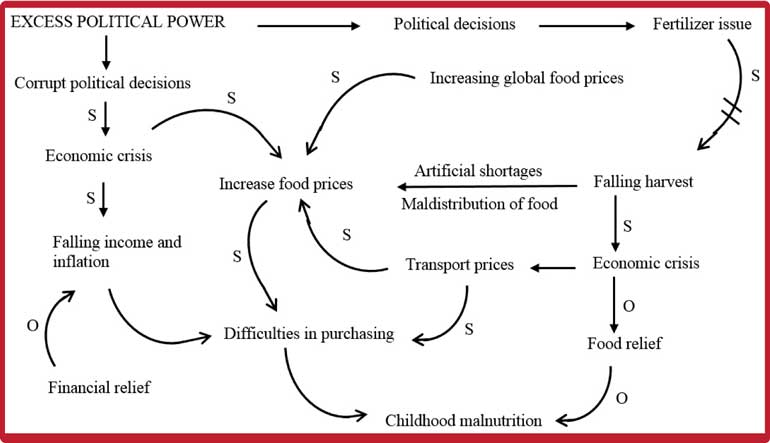

Systems thinkers will attribute skyrocketing food prices in Sri Lanka (i.e. trend) to a number of underlying systemic structures such as a corrupt economic system, erratic farming practices, fluctuating global food prices, and a dysfunctional transport system

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Many are familiar with the parable of the “blind persons and the elephant”. It’s the story of a group of blind persons who had never seen an elephant previously, are required to touch an elephant to learn what it is like. Each one has the opportunity to feel only one part, and they come up with individual explanations. The one feeling only the trunk claims that the elephant is like a branch of a tree branch, while the one who feels the tail thinks the elephant has a shape of a rope! Most of us are like these blind persons, seeing only a tiny narrow part of a wider system.

When we hear calls for a “systems change” in Sri Lanka, do we mean we want to change the tail or the elephant or its trunk or its ears?

This article describes a scientific approach to the concept of ‘systems’ and how ‘change’ could be brought about. The first part is an introduction and the second applies this knowledge to understand the current crisis in Sri Lanka. Systems thinking (or viewing the world through the lens of systems) complements other ways of looking at the world.

2. Systems

What is a system?

A system is a set of things or ‘agents’ working together as parts of an interconnecting network or web. The individual ‘agents’ function according to a set of rules and all of them form a unified whole. These interconnections are often multiple and include feedback loops. As the elephant parable shows, the properties of the whole system are very difficult to predict by examining the behaviours of its individual agents. The discerning reader will note that the Interpretations or explanations given to the current Sri Lankan crisis are often based on individual’s experience. They tend to describe the tail or the ears or the trunk of the elephant, and rarely the whole elephant!

Types of systems: Open and closed systems

The more predictable systems are often mechanical and artificially created systems. An example is a watch. These are ‘closed’ systems because its environment has little influence on the system. In contrast, a plant is an example of an ‘open’ system. It is a naturally occurring system that uses sunlight and carbon dioxide, and water absorbed by the roots, to produce energy and food. An example of a social system is a school, with its students, teachers, and classes, functioning according to rules of behaviour. Natural and social systems are ‘open’ systems that interact with the environment.

3. Systems thinking

Systems thinking is the application of systems to the way you think! Peter Senge, Author of the Fifth Discipline states this beautifully: “Systems thinking is a discipline for seeing wholes. It is a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing ‘patterns of change’ rather than ‘static snapshots’. It forces us to “look beyond personalities and events and look into the underlying structures which shape individual actions and create the conditions where types of events become likely” (1).

Systems thinking views the patterns of events (or symptoms) of a system as ‘emergent’ properties. These are determined by the interactions in the underlying sub-systems (e.g. socio-economic classes). These have evolved over a period of time (i.e. they all have a history). The trends in the events give us a clue to the way the underlying determinants or subsystems are interacting or changing (2).

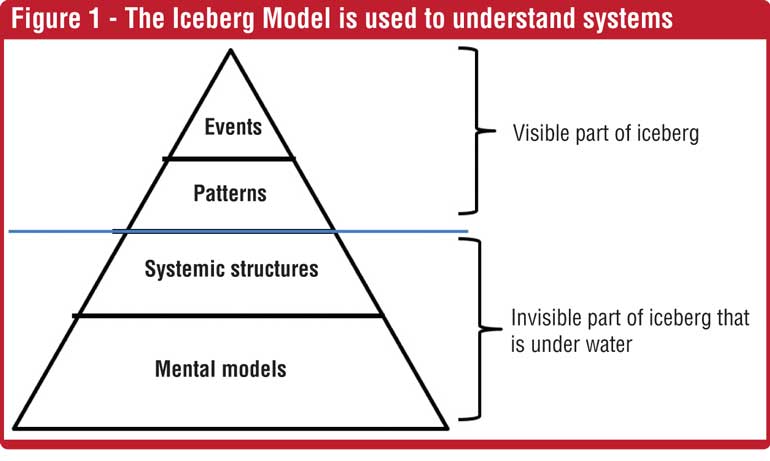

The Iceberg Model describes how events and patterns (which are the phenomena we can easily observe) are ‘caused’ by systemic structures and mental models. The latter two are often hidden from view or our experiences. In a social system, there are several such systemic structures: the hierarchies observed in organisations, rules and procedures, social status of people, methods of incentives, compensation, goals, attitudes, corporate culture, feedback loops and delays in the system; and underlying forces that exist in an organisation. Behaviours derive from these structures, which are (in turn) established due to mental models or paradigms. “A fundamental systems thinking concept is that different people in the same structure will produce similar results” and “the structure causes 85% of all problems; not the people!” (2).

Accordingly, systems thinkers will attribute skyrocketing food prices in Sri Lanka (i.e. trend) to a number of underlying systemic structures such as a corrupt economic system, erratic farming practices, fluctuating global food prices, and a dysfunctional transport system.

3.1 Understanding system structures

There are several methods or tools available to deconstruct and understand the structures hidden in social systems (3)

3.1.1 Social Network Analysis is known as an “X-Ray” for complex systems which reveals the invisible but hidden web of relationships that make systems function. It gives a visual representation of a network, and identifies critical actors and leverage points.

3.1.2 Ethnography is a tool used by anthropologists and gives an “insider’s perspective” on the social relations and dynamics in a given context. It assists in identifying actors, processes, and institutions that tend to be hidden, and reveals local rationales for actions.

3.1.3 Participatory Systems Analysis uses the system actors to interact, learn from each other, describe the interactions in a system and find feasible areas for collaboration. It is not a tool but more an approach where multiple tools (e.g. causal loop diagram described below) can be used to help the actors analyse the system they belong to.

3.1.4 Causal Loop Diagrams conceptually model systems in a holistic manner. This is perhaps the easiest to understand and will be described in a bit more detail.

This simple tool helps you to map how variables (i.e., factors or processes) influence one another. It is a network like diagram to depict various components of the system using arrows and nodes. The key factors or variables in a system (i.e. the “nouns” or nodes) are linked to each other along the networks of paths. These links show the causal relationships between the links (i.e. the “verbs”). Linking together several loops creates a summary of a story about a particular problem or issue. These diagrams are particularly useful to reveal a system’s underlying feedback structures. It also helps to identify high and low leverage points in a system. Individuals or teams can develop their own causal loop diagrams.

A causal loop diagram consists of four basic elements: the variables, the links between them, the signs on the links (which show how the variables are interconnected), and the sign of the loop (which shows what type of behaviour the system will produce). By representing a problem or issue from a causal perspective, you can become more aware of the structural forces that produce puzzling behaviour. See Figure 2 which attempts to describe the multiple causal factors that could lead to childhood malnutrition. In this figure, S stands for ‘same direction’ i.e. a positive influence. For example, an increase in global food prices leads to increasing local food prices. The letter ‘O’ stands for ‘opposite direction’ or a negative effect, e.g. more and more financial relief would buffer falling income of households.

4. Changing a system

When studying this diagram, the reader will understand how difficult it is to intervene to solve a problem such as malnutrition. One could attempt to intervene in several areas. For example, provide financial relief, and food relief and take measures to overcome the political crisis.

However, there is another approach. These are places in the system where ‘a small change could lead to a large shift in the behaviour’ of the system. These are what we call ‘points of power’ or leverage points. The call for ‘Systems Change’ in Sri Lanka, too should identify these Leverage Points.

4.1 Drivers or leverage points

Simply selecting a few ‘magic bullet solutions’ has its dangers. This is because of feedback loops could lead to unexpected or unintended consequences! This is described as the Cobra Effect (see https://ourworld.unu.edu/en/systems-thinking-and-the-cobra-effect).

“A famous anecdote describes a scheme the British Colonial Government implemented in India in an attempt to control the population of venomous cobras that were plaguing the citizens of Delhi that offered a bounty to be paid for every dead cobra brought to the administration officials. The policy initially appeared successful, intrepid snake catchers claiming their bounties and fewer cobras being seen in the city. Yet, instead of tapering off over time, there was a steady increase in the number of dead cobras being presented for bounty payment each month. Nobody knew why”… until they discovered the entrepreneurial spirit of the cobra catchers who had set up clandestine breeding sites! When the bounty was cancelled, the breeders, released the now worthless cobras, worsening the problem!

Pioneer system thinkers e.g. Forrester and Donella Meadows describe this counterintuitive nature of some leverage points (4). Though these points in a system are often known, it is important to appreciate that pushing them could even change the system in the wrong direction.

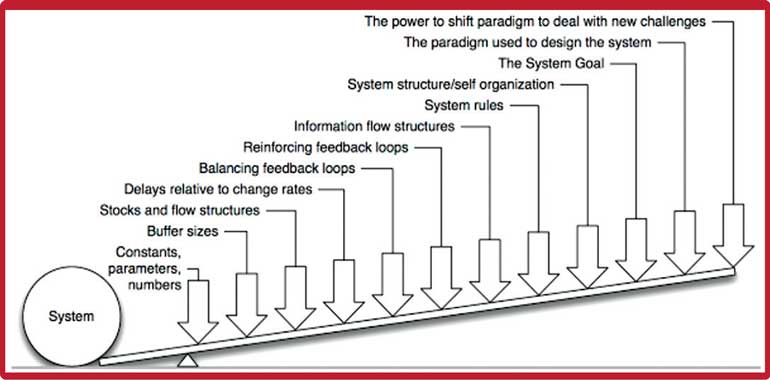

Two ways of classifying leverage points are described. Meadows described a list of 12 and they are listed in increasing order of effectiveness. A simpler adaptation of this is given in the Intervention-Level Framework (ILF).

4.1.1 Meadows leverage points

12. Constants, parameters, numbers: This is equivalent to increasing funds to purchase food

11. The sizes of buffers and other stabilising stocks, relative to their flows. For example, the dams and tanks that help to provide water for irrigation throughout the year, and a regular supply of hydropower.

10. The structure of material stocks and flows. An example is a transport network. Colombo has a handful of main transport links which restrict the inward and outward movement of people.

9. The lengths of delays. Delays relative to the rate of system change can affect the evolving system and cause oscillations. For example, the delay in training doctors will lead to higher than required numbers. Curtailing this by reducing university placements would lead to a delayed reduction in numbers.

8. The strength of negative feedback loops. This is relative to the impacts they are trying to correct against. The thermostat

7. Influencing positive feedback loops. These are incentives or factors that feedback. The higher the interest rate, the larger the volume of money in the bank. This will yield still higher earnings. The more people who get infected with COVID-19, the more others get infected. Interventions include dampening the positive feedback, for example the use of masks to curtail the spread.

6. Information flows and its structures. Access to information affects the system. A well-known example is how electricity meters are located to be easily seen by consumers, significantly reducing power consumption in households.

5. The rules of the system. These are the incentives, laws, norms and other measures of control or facilitation that are in a system.

4. Self-organisation: The power to add, change, evolve, or self-organise system structure. Some social systems and living systems, change themselves by modifying or creating new structures and behaviours. This is called self-organisation. Self-organisation means changing aspects of a system on this list such as new rules, new negative or positive loops, and new structures.

3. The goals of the system

The goals of a system are larger, less obvious and have higher leverage, even superior to the self-organising ability of a system. For example, “If the goal is to bring more and more of the world under the control of one particular central planning system, then everything further down the list, physical stocks and flows, feedback loops, information flows, even self-organising behaviour, will be twisted to conform to that goal”.

2. The mindset or paradigm out of which the goals, structure, rules, delays, and parameters arise.

“The shared idea in the minds of society, the great big unstated assumptions — unstated because unnecessary to state; everyone already knows them — constitute that society’s paradigm, or deepest set of beliefs about how the world works”.

1. The power to transcend paradigms

Meadows states the following: It is to “get” at a gut level the paradigm that there are paradigms, and to see that that itself is a paradigm, and to regard that whole realisation as devastatingly funny. It is to let go into Not Knowing, into what the Buddhists call enlightenment (4).

4.1.2 The Intervention-Level Framework (ILF)

This is an adaptation of Donella Meadows’ list of 12 places to intervene in complex systems (5). These 12 points of intervention have been collapsed to 5 more mutually exclusive levels: the levels of paradigm, goals, system structure, feedback and delays, and structural elements.

Paradigm:

“The shared idea in the minds of society, the great big unstated assumptions — unstated because unnecessary to state; everyone already knows them — constitute that society’s paradigm, or deepest set of beliefs about how the world works”. In the case of the Sri Lankan crisis, the paradigm has changed. Political power is being challenged in the streets by a once docile class of people and youth. People are protesting about increasing rates of malnutrition.

Goals

The goals of a system are larger, less obvious and have high leverage. The call for “Systems Change” is such as goal. If this is articulated clearly, it could change things further down the list, in order to conform to that goal. Other goals that are heard in the current discourse include ‘eliminate hunger and malnutrition’.

System structure

These are the rules of the system (for example the incentives, laws, norms and other measures of control of the food supplies and consumption) that are in a system, and the ability for self-organisation (i.e. means changing aspects of a system on this list such as new rules, new negative or positive loops, and new structures).

Feedback and delays

Feedback loops and delays. For example, inefficiency in distribution of crops produced in Sri Lanka would lead to the excess being stored in agricultural areas and financial losses among farmers. These are disincentives to the farmers who will produce less in future. Increasing imports may curtail costs, but would further discourage local farmers and their distributive networks.

Structural elements

These are the parameters, the buffers and other stabilising stocks relative to their flows. For example, the storage facilities (i.e. stocks) for post-harvest crops that help to buffer prices throughout the year, and the transport network which is the flow to and from these stocks.

The Sri Lankan crisis: A systems approach

Sri Lanka is facing an unprecedented crisis due to multiple interacting factors: a corrupt political system, rising prices of commodities globally, COVID-related global economic disorder and so on. Some would identify corruption as the key factor in the process. From a system’s thinking perspective, these multiple crises are symptoms or events in the iceberg. Underneath lies the structures that have several interrelated factors. What are these systemic factors that lead to the emergence of a crisis? This will be discussed next week.

References:

1. How to do (or not to do)…using causal loop diagrams for health system research in low and middle-income settings, Health Policy and Planning, 2022;371328

2. What is Systems Thinking? A Review of Selected Literature Plus Recommendations American Journal of Systems Science 2015;4:11

3. Local Systems Practice: User’s Guide. The Local Systems Practice Consortium https://sites.google.com/view/lsp-users-guide/home

4. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. By Donella Meadows Edited By Diana Wright, Sustainability Institute

5. Systems Science and Obesity Policy: A Novel Framework for Analyzing and Rethinking Population-Level Planning. American Journal of Public Health 2014;104:1270

(The writer holds an MBBS (Col), MD (Col), MRCP (UK), MD (Bristol), Ph.D (Col), FRCP (Lond), FCCP, FNASSL, and is an Emeritus Professor of Medicine and Consultant Physician.)