Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday, 31 October 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka produces approximately 330 million kg tea per year and every kilo is sold at the highest prices in the world, a value dictated by the uniqueness of “Ceylon Tea”. To dilute that advantage by the uncritical emulation of the highly-efficient, volume-driven strategies of multinational giants who rely on cheap, multi-origin packs, is a sure recipe for disaster. Selling cheap, one can only scramble at the bottom end for an uncertain survival – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

At its recent 18th Annual General Meeting, the Tea Exporters’ Association (TEA) renewed its strident demand for liberalisation of the tea industry, ostensibly to “modernise and end the downfall of the industry” and seemingly driven by a laudably altruistic motive.

In reality, it was once again a pathetic plea for State patronage for the importation of black tea from other producer countries, in order to resuscitate the flagging fortunes of unenterprising exporters/traders through the injection of cheap tea in to their blends.

Before the TEA came in to being 18 years ago, all industry interests were represented by the Ceylon Tea Traders’ Association (CTTA), with proportional representation from the trading segment, the producers-planters and brokers. It was an inclusive platform which facilitated the discussion of sectoral interests and problems, but without divorcing itself from the common objective of ensuring the wellbeing of the industry.

At the outset itself one must bear in mind that the TEA is promoting only its personal interest and objective, irrespective of the potential toxic fallout in relation to the industry in general. This is clearly demonstrated by the TEA call for State sanction to isolate itself from the industry proper, by being placed under the Trade Ministry.

The multi-faceted tea industry in Sri Lanka represents the plantation worker, the small holder, the corporate plantation owner, the private factory owner, and a myriad ancillary service providers. The exporter is only one link at the end of a long chain and not the most important.

The producer segment represents, conservatively, at least two million people, equivalent to 10% of the population of the country; those at the bottom end of the income ladder whose daily bread depends on the overall health of the industry.

Any damage to the industry arising from an initiative designed to benefit a disaffected minority group will irreparably hurt the lives of this larger segment. Any proposal with potential for a wide-ranging impact on the industry must take consider the above aspect which is of genuine national importance and relevance, unlike the parochial nature of the TEA’s woes.

“Politicisation”

Permit me to address the many positions articulated by the TEA, as reported in the Daily FT of 23 October.

The TEA claims that the industry has become “highly politicised” and a “national burden”. Surely, the reality is that the political aspect of the industry was removed with its total re-privatisation in 1992, as it was pre-1977. In fact, the State relieved itself of a “national burden”. Therefore, the TEA claim of “politicisation” is contradictory, lacks validation and unsupported, but yet a recurrent refrain in the articulation of TEA grievances.

The Government and the relevant ministries and entities are mandated to act in the interests of the industry in its totality, and the millions it supports. That responsibility cannot be sublimated to provide a crutch to a small group of faltering commercial adventurers. What the TEA is now seeking is political patronage in order to bolster its declining fortunes.

The TEA claims that “high controls close opportunities for foreign investments, opportunities for local firms to expand”. The one controlled aspect of the local industry is the restriction on importation of cheap tea, when a product of similar configuration is produced in large volumes in this country. The arithmetic of cheap imports is ridiculously simple, irrespective of the item under consideration. A cheaper imported substitute or equivalent will immediately devalue the local product or render it unsellable.

To cite one recent example, locally produced pepper which was selling at Rs. 1,300/kilo just one year ago has now declined to Rs. 700/kilo as a consequence of cheap imports into the country. The resultant impact on the local pepper industry does not need further elaboration.

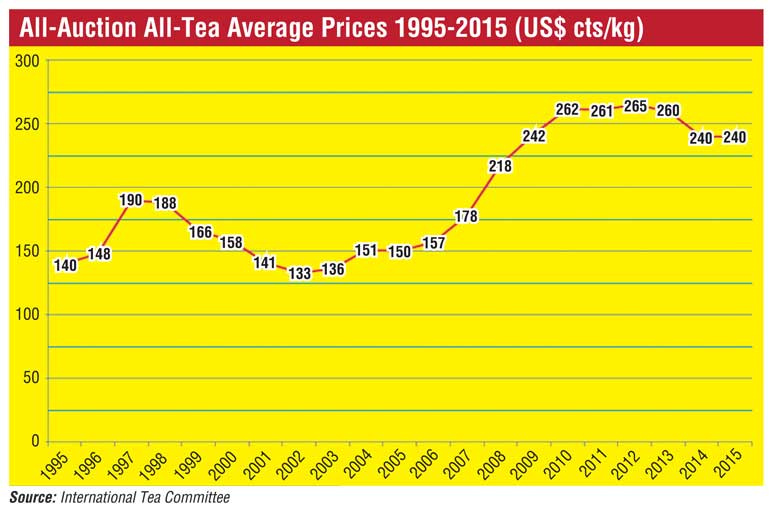

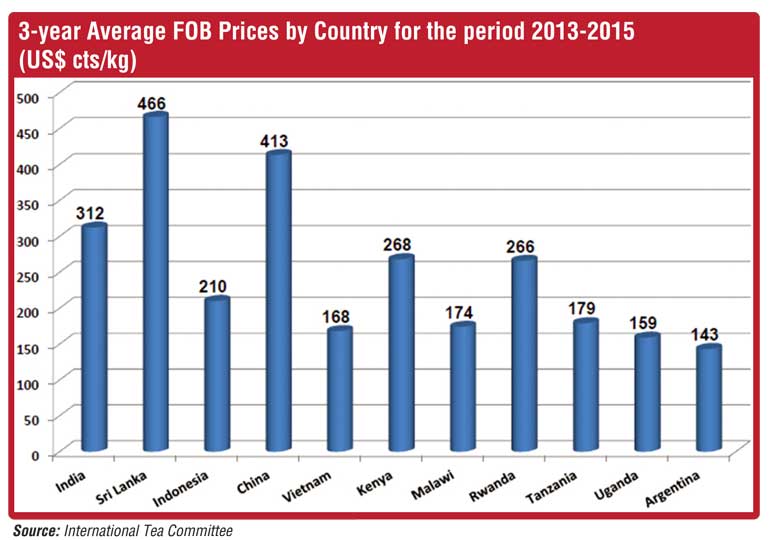

As seen in the graph, the all auction average price of tea varied from $ 2.65 in 2012 to $ 2.40 in 2015. The graph demonstrates the average FOB price during the same period (2012-2015) in respect of the major producer-exporters. The Sri Lanka FOB price of $ 4.66 is $ 1.54 more than India and $ 2 more than that of Kenya, the most serious competitor to Sri Lankan tea in the global market. The Sri Lanka price is also close upon $ 2 more than the highest global auction average for the same period.

The impact of cheap imports, irrespective of source, will immediately diminish the Colombo auction prices proportionately and compel the local producer to sell well below COP, at unimaginably destructive consequences to the millions of dependents of the industry, particularly at rural and plantation level, whilst resurrecting and enriching a small segment of exporters/traders. The socio-economic consequences of diminished earnings of a substantial segment of the population, currently existing just above subsistence level, would then become the actual “national burden” that the TEA is so glibly asserting.

In essence, what the TEA is proposing as a strategy to overcome a purely sectoral problem, is to squander foreign exchange on cheaper imports, thus diminishing the local auction price and the FOB price, which will automatically result in the diminution of foreign exchange earnings for the country from the export of tea. The national foreign exchange earnings can be grown only by increasing the export price and not by reducing it, as proposed by the TEA.

“$ 5 billion industry”

The TEA believes that with liberalisation “Sri Lanka has the potential to become a $ 5 billion industry”. Given that exporting at $ 4.66 we make $ 1.5 billion annually, the claim that it can be grown to $ 5 billion by selling cheap defies all economic, financial and statistical logic.

As for State protection for an important national product, which defines and brands the country globally, one need not look further than France, where the production style, region of manufacture and nomenclature of “Champagne” is rigidly governed by law and the importation of any equivalent product prohibited. It is guarded by an internationally enforceable covenant which prevents a similar product in any other country being marketed as “Champagne”.

Historically, the tea industry in Sri Lanka has been exploited by the foreign/multinational exporter, starting with the British who gave birth to the industry. For decades we have submissively supplied bulk tea to multinationals, who have added value to our product elsewhere and enriched themselves whilst conceding a mere pittance to the dependents of the local industry.

Having first captured other markets on the brand uniqueness of “Ceylon Tea,” these entrepreneurs then reduced the “Ceylon Tea” component in their blends with cheaper substitutes from other destinations and enlarged their profits. What the TEA is proposing is extending that same servile service to masters who have no affiliation or loyalty to the country of origin, at potentially-debilitating consequences to this country.

For example, when the dismantling of the Soviet Republic provided an excellent opportunity for Sri Lankan exporters to develop local brands for international marketing, most of our exporters chose the easier, well-travelled route and became packers for new entrants to the Russian market. The result was that in just a few years Russians expanded markets on the strength of “Ceylon Tea,” but gradually reducing their cost and increasing profit by substituting the Ceylon Tea component with cheaper imports from elsewhere.

The TEA, by its own statements, continues to contradict their rationale for the liberalisation of imports. On the one hand it criticises the Government for not advertising “Ceylon Tea” using a dual promotion strategy – unspecified – similar to what other countries and products have done. “…Ceylon Tea is a part of a brand concept like Scotch Whisky. This is what we want the Government to do with the Rs. 7 billion fund.”

If the uniqueness of “Ceylon Tea” is comparable to the exclusivity proposition of Scotch Whisky, then why propose its dilution with cheap additives? In fact, does a cheap, diluted product warrant an expensive marketing campaign? Does the Scottish “Single Malt” producer dilute and cheapen his product with low-priced imported components?

A successful branding strategy founded on a “Unique Selling Point” to capture a market is diametrically opposed to the concept of cost reduction with a cheap component, and are two mutually-exclusive propositions.

Dismissing “Pure Ceylon Tea”

Demonstrating another example of confused thinking, the TEA dismisses the “Pure Ceylon Tea” concept, commenting that it “…accounts for less than 10% of the annual tea export volume, and that the representative brands are unable to drive the tea industry to achieve expected growth…”

In fact, that statement represents the mindset of the timid and unenterprising exporter and is the very reason why a few exporters sell comfortably at $ 10 per kg, FOB, whilst the other struggles for survival at $ 3 per kg. The reality is that it is the locally-owned brands, exporting exclusively “Pure Ceylon Tea,” which are the flag-bearers for the national product, on the global stage.

The TEA speaks of the inability of certain exporters to cater to specific markets due to the “unavailability of suitable types of tea locally…” This country produces a greater variety of grades of black tea than possibly any other country whilst the Government permits the importation of Darjeelings, Green Tea and other speciality types, which are not typical products of our industry. What other type of tea would the TEA have in mind for import? If it is CTC tea, we are free to increase production volumes locally if there is a corresponding increase in the external demand for it.

The TEA has cited, not for the first time, the garment industry as an example of the success of liberalisation. The garment industry is different from the tea industry as chalk is from cheese. In the apparel sector 90% of the raw material is imported and value addition at our end is in terms of skill and sweat. It bears no comparison with the tea industry, in which literally every constituent component is locally produced.

The two attached graphs clearly demonstrate that international and local firms moving out of Sri Lanka in search of lower cost tea will not have even a minimal impact on the local FOB price or auction levels. That is exactly what those members of the TEA who are seeking a cheaper source should do, without strategising to cheapen this source.

“Race to the bottom”

Bill Gorman, speaking at the recently concluded 150th year tea anniversary celebrations, referred to the “race to the bottom” now taking place in the UK tea market, in which the consumer is compelled to accept low quality tea shorn of its beneficial features. What the TEA proposes is a similar downward journey for “Ceylon Tea,” at its very source.

Sri Lanka produces approximately 330 million kg tea per year and every kilo is sold at the highest prices in the world, a value dictated by the uniqueness of “Ceylon Tea”. To dilute that advantage by the uncritical emulation of the highly-efficient, volume-driven strategies of multinational giants who rely on cheap, multi-origin packs, is a sure recipe for disaster. Selling cheap, one can only scramble at the bottom end for an uncertain survival.

The TEA call for liberalisation of imports is driven by the same sense of insecurity generated by the rapidly-diminishing profit margins of the proponents. The TEA proposes to sacrifice every advantage “Pure Ceylon Tea” has, in favour of immediate personal survival and gains that are certain to be short-term, whilst the damage caused to the local industry will be permanent and irreparable.

Given the importance of the tea industry to a significant proportion of the population of this country, that would be an act of treason.

Exploitative thrust

The exploitative thrust of the Western-based multi-national packer/marketer of a third world product is best exemplified by coffee. For every plastic cup of coffee sold for $ 3-4, in affluent societies, the farmer in Africa gets five cents. From a kilogram of coffee beans sold at $ 2.75,110 cups can be brewed, translating to a profit margin of over $ 300 for those in between the poor farmer and the rich consumer. That mirrors the story of tea as well and the proposal of the TEA would be to contribute to that unacceptable socio-economic disequilibrium.

Internally, our tea industry is confronted by rising costs and stagnant productivity and, externally, by the of diminution of Sri Lanka tea in multinational brands, expanding production in other growing countries, the steadily growing gap between global production and consumption, further compounded by the threat to tea, globally, posed by competing beverages.

In the face of these multiple challenges, unless all stakeholders of the industry unite and establish a commonality of purpose within, the industry will fail in its totality. Isolating oneself from the group and seeking an individual solution will, at best, provide a temporary and marginal gain. Division means eventual disintegration whilst in unity there is strength.

In the course of a 66-year involvement in the tea industry, I have invested in its every segment – plantations, brokerage and value-added exports, a commitment which extends from the bush to the supermarket shelf.

“Dilmah,” the only fully Sri Lankan-owned international brand, owes its position of international pre-eminence to the concept of “Pure Ceylon Tea”. That concept will be destroyed if the TEA proposal to import tea is sanctioned. The consequences to the industry in its totality, particularly the dependent rural and plantation economies, as explained in this writing, will be devastating.

Other principled exporters will also suffer a similar fate and, as a citizen and an individual who has dedicated a lifetime to tea, I consider it my duty to do everything within my capacity to prevent the dismantling of this industry.