Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 14 November 2023 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In recent years, the spectre of corruption and the lack of transparency have clouded Sri Lanka’s

In recent years, the spectre of corruption and the lack of transparency have clouded Sri Lanka’s

appeal as a location for foreign investments. Tackling corruption and lack of transparency is both a moral and an economic need if Sri Lanka is to take advantage of the rewards that foreign investments can offer.

FDI inflows to Sri Lanka have supported the growth of industries, employment creation, and export promotion as it drives the transfer of capital, knowledge, and technology know-how from foreign investors. Foreign investments in Sri Lanka have primarily gone into property development, manufacturing, and services sectors such as tourism, telecommunication and IT/BPO. Despite providing extremely generous tax holidays, Sri Lanka has only been able to draw in about $ 1.2 billion in foreign direct investments, including foreign loans to Direct Investment Enterprises (DIEs), annually, on an average since 2010. FDI including loans totalled $ 1.18 billion in 2022, an increase from $ 0.8 billion in 2021. $ 1.1 billion of the total FDI inflow, including loans, went to BOI-registered companies. FDI excluding loans amounted to $ 0.9 billion in 2022, compared to $ 0.6 billion in 2021 (CBSL Annual Report 2022).

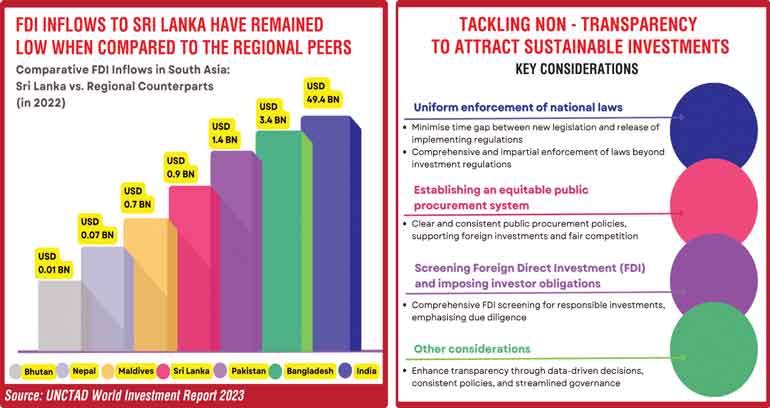

Foreign investments to Sri Lanka have remained low compared to its regional peers over the past few decades due to various legal, structural, and institutional shortcomings. These include restricted labour market regulations, convoluted and inconsistent tax structures, and tedious regulatory frameworks pertaining to contract enforcement, trade facilitation, land acquisition, and the lack of well-developed infrastructure facilities. In addition to these variables, lack of transparency, policy ambiguity, institutional flaws, and governance deficiencies have contributed to deter foreign investors. Despite being the first nation to liberalise its economy in the South Asian region, Sri Lanka’s regional counterparts, such as India ($ 49.4 billion in 2022), Bangladesh ($ 3.5 billion in 2022) and Pakistan ($ 1.4 billion in 2022) have surpassed FDI inflows to Sri Lanka ($ 0.9 billion in 2022) during the period 2017-2022 (UNCTAD World Investment Report 2023).

Non-transparency in Sri Lanka

For the purpose of this article, “non-transparency” will be defined as government policies or structures that impede the efficient flow of direct investment between countries by imposing implicit costs and information asymmetries on the investors. In the context of Sri Lanka, non-transparency implies ambiguous government regulations, covert decision-making procedures, and restricted access to data that investors and the public should have full access to. Lack of accountability in public institutions, undisclosed financial dealings, and bureaucratic red tape are only a few instances of the numerous forms that non-transparency can take. Due to this lack of transparency, investors may find it difficult to accurately assess risks and forecast opportunities and outcomes, which weaken trust and confidence in the business ecosystem.

Legal and regulatory framework

To encourage and safeguard foreign direct investments, Sri Lanka has investment laws and a judicial system to address investor concerns. Moreover, the country is a member of the World Bank Group’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA). Sri Lanka has bilateral agreements in place to protect investors’ interests through Double Tax Avoidance Agreements with 45 countries and Investment Protection Agreements with 28 countries. In 2021, the Colombo Port City Special Economic Zone (SEZ) and the Colombo Port City Economic Commission (CPCEC) were established. In addition to the provisions in the Constitution of Sri Lanka, some of the laws that directly or indirectly regulate acquisitions and investments by foreign nationals and investors include: the Foreign Exchange Act of 2017 and Foreign Exchange (Classes of Capital Transactions Undertaken in Sri Lanka by a Person Resident Outside Sri Lanka) Regulations of 2021 (FEA and the Regulations); the Board of Investment Law of 1978 (BOI Law); the Strategic Development Projects of 2008 (SDPA); the Colombo Port City Economic Commission of 2021 (CPCEC Act); the Commercial Hub Regulations of 2019 issued under the Finance Act of 2012 (as amended, the Commercial Hub Regulations); and the Land (Restrictions on Alienation) Act of 2014 (LRA).

Despite the numerous laws, the difficulty in Sri Lanka is that the laws are not enforced reliably and transparently. In most cases, the laws and regulations are weak, inconsistent, and selective.

Challenges

The Technical Assistance Report, Governance Diagnostic Assessment published by the IMF in September 2023 revealed several systemic weaknesses in public administration that lead to corruption across a range of state functions. According to the findings of the report, the lack of oversight and transparency around the operation of state enterprises worsened corruption vulnerabilities, especially regarding procurement and other forms of contracting, and capital investments. The lack of transparency in public procurement contributing to high levels of political engagement in the selection of procurement winners, granting of concessions for strategic investments, risks of corruption in contract enforcement, and a lack of oversight of procurement processes and outcomes were some of the challenges identified in the report. Long before the IMF released its Diagnostic Assessment in September 2023, these challenges were under public scrutiny. In the absence of transparency, sustainable foreign investments intended to spur economic growth would have minimal effect. In the medium to long run, this could cause more harm than good.

Legal and regulatory reforms to improve transparency

A legal and regulatory framework that is out of date cannot be used to draw in and profit from FDI inflows. Unnecessary laws and regulations that are abused as red tape and are poorly implemented hinder investments. In addition to a strong legal and institutional foundation, political will, administrative restructuring, and digitalisation to improve efficiency in the public sector are also necessary to create a stable investment climate and build investor confidence.

Improving the overall investment climate should be supported by the effective enforcement of suitable national laws aimed to attract, facilitate, and sustain foreign investments. It is important to minimise the amount of time taken between passing new legislation and issuing regulations that implement it. The full potential of legislative reform initiatives aimed to attract FDI inflows and enhance investor protection could only be realised if executive regulations are swiftly adopted and effectively enforced by appropriate authorities across all governmental levels.

Moreover, investment law by itself is insufficient in the absence of necessary laws and regulations in all other areas. Other pertinent laws, rules, and regulations that affect investments directly or indirectly (such as Customs Ordinance, labour laws, environmental protection laws, Intellectual Property (IP) laws, competition law, data protections laws, tax laws, alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, and public-private partnership laws) should be comprehensive and enforced impartially. Upholding strict intellectual property rights, protecting land rights, preserving contractual rights, and access to streamlined dispute resolution procedures, are feasible by the impartial enforcement of relevant laws.

Foreign companies would be less likely to submit bids and invest if the domestic procurement policies are vague and inconsistent. Economical (best value for money), efficient (does not delay the project), equitable (does not discriminate bidders based on political affiliations, for example), and transparent (publicising what is involved, process followed, and outcomes) are tenets of a good public procurement system. It would encourage as many qualified firms as possible to compete based on price while ensuring that quality objectives are met.

One of the objectives of Sri Lanka’s 2023 IMF program is to create an online fiscal transparency platform. Although this objective has not been fulfilled thus far, the platform aims to promote transparency in the public procurement system by making public procurement contracts and other information more widely available. The objective emphasises the importance of clear and unambiguous rules for public tendering, price-based contract awarding, and full disclosure to attain transparency. To facilitate an effective public procurement system, procuring agencies should follow coherent national policies and standards. The institutions should adhere to a uniform framework that reduces politicisation and subjective judgments for the evaluation and approval of tenders.

To attract profitable and sustainable investments, a far-reaching regulatory framework would help investors understand the size of the garden (where investors can play) and the height of the fence (to keep out malign actors). Driven by geopolitical developments, investor screening should be a key policy consideration to attract responsible investors. This would encourage healthy competition and deter malign foreign investors. An evaluation of investor credibility and alignment with development priorities should be the first step in the screening process, followed by a business plan and compliance screening. It is imperative to perform due diligence to ensure compliance with legal and regulatory requirements prior to granting approval.

Reducing vulnerabilities and excessive reliance on a small number of foreign investors should be the goal of a non-discriminatory FDI screening procedure. A biased screening process that is not merit-based could lead to a discriminatory investment environment that benefits a select few.

Improving transparency to attract FDI does not mean that Sri Lanka should be passive recipients of investments from abroad. Provisions of the domestic law should reflect the growing awareness of the need to promote and implement responsible business conduct in the host-country. A growing trend in international investment law is the inclusion of investor obligations to protect human capital, environment, and other public policy goals. In recent years, many countries including Germany, France, UK, and the Netherlands have passed Acts mandating due diligence and responsible business conduct. Such laws and regulations would ensure that investors contribute to sustainable development goals (i.e., productivity and innovation, job quality and skills, gender equality, and decarbonisation).

Improvements to transparency should come from data-driven and evidence-based decision making, consistent policy, prompt updates on regulatory changes, standardised procedures to monitor breaches and appropriate remedial mechanisms. There needs to be a stronger commitment to improve governance, which includes cutting back on red tape and bureaucratic discretion. The coherence and consistency of policy would be enhanced by rationalising the number of government bodies influencing investment policy and streamlining coordination between pertinent ministries and agencies.

Conclusion

The country’s current crisis stems from poorly planned infrastructure projects funded by foreign commercial loans (like the Chinese FDI projects that came in the form of debt) and lack of fiscal transparency leading to misused government finances. Moving forward, it is important to critically assess the sustainability and calibre of foreign investments based on how they support the development of domestic industries, advance innovation capacities through the transfer of knowledge and technology, generate employment opportunities, advance gender equality, and ease the transition to low-carbon energy sources.

Transparency is a prerequisite for responsible investors seeking mutually beneficial partnerships. By prioritising transparency and accountability, Sri Lanka can lure investments that align with long-term development objectives and generate return on investment. Sri Lanka’s economic landscape necessitates a commitment to transparent governance that not only benefits foreign stakeholders but also steer the country towards a strong economy, where sustainable foreign direct investments act as a catalyst for growth.

(The writer has a penchant for international trade and development. With a background in economics and international business, she holds an MSc in International Business Management (UK), and is currently pursuing an LL.M (UK), specialising in Commercial Law. She can be contacted via [email protected])