Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 29 December 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

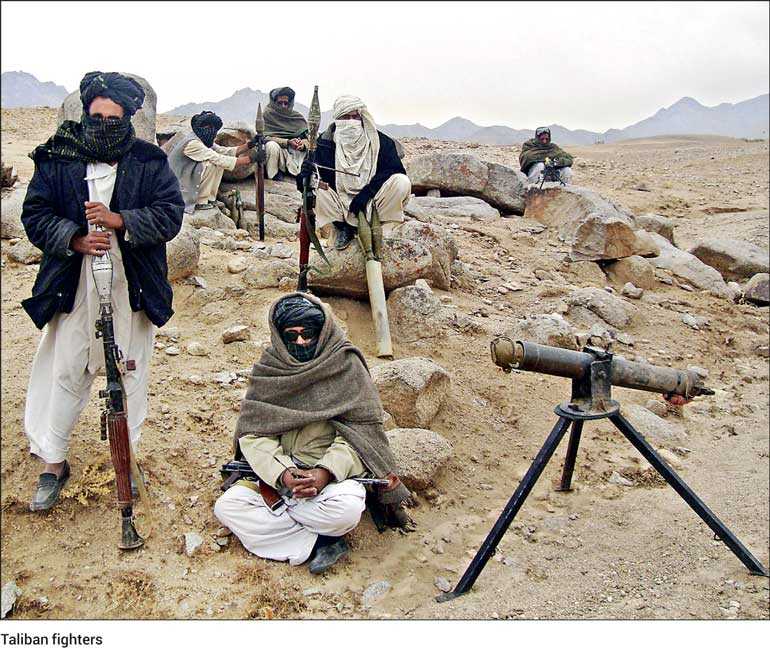

Given the global powers’ very determined efforts to bring peace to war-torn Afghanistan by talking to the Taliban, it is likely that the radical Islamic insurgent group will be in the seat of power sooner or later.

The Taliban are no strangers to State power. They ran a government called the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” between 1996 and 2001. Before 1996, they were an insurgent group. And after being ousted from power by US-led forces in 2001, they returned to insurgency and have continued to be rebels, to date.

Nevertheless, while being quintessentially anti-systemic, the Taliban have been exercising full or partial “de facto” control over much of Afghanistan, running a state within a state as it were.

There were glimmerings of change in the outlook of the anti-systemic Taliban in 2003. Since then, they have been seeing themselves not just as an insurgent group destroying everything and every institution that they consider “un-Islamic”, but also as an administrative group, delivering social, economic and other State-like services to people in areas under their control or areas in which they share power in varying degrees with the legitimate government headquartered in Kabul.

Changes in environment

The reorientation of the Taliban is due to changes in the political and geo-strategic environment. The US has of late been showing an increasing inclination to disengage from Afghanistan militarily and is having talks with the Taliban to bring about an “Afghan-negotiated” peace settlement which will end the war while ensuring that the social and political gains of the democratic interregnum remain.

The reorientation of the Taliban is due to changes in the political and geo-strategic environment. The US has of late been showing an increasing inclination to disengage from Afghanistan militarily and is having talks with the Taliban to bring about an “Afghan-negotiated” peace settlement which will end the war while ensuring that the social and political gains of the democratic interregnum remain.

The US had roped in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and the Haqqani Network for preliminary talks with the Taliban in Qatar recently. The Saudis have been funding the Taliban. Pakistan has provided bases and personnel to them. And the Haqqani Network, known for its military prowess, is part of the Taliban.

By talking to the Taliban with a plan to withdraw its military from Afghanistan, the US had met the Taliban’s most important pre-condition for negotiations.

If all goes well, an estimated 22,000 Western troops, including 14,000 from the US, are likely to get back home, though no official commitment to a total withdrawal has been announced yet. The 17-year Afghan misadventure has cost the US $1 trillion to date. Remember, the US and its allies had, at one stage, 130,000 troops in Afghanistan.

The US had had to keep its client regime in Kabul, led by President Ashraf Ghani and CEO Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, out of the talks at the insistence of the Taliban. But the incumbent regime in Kabul is being kept informed about developments.

As for President Ashraf Ghani, he had formed a team to negotiate peace with the Taliban for a settlement which is “Afghan-owned and Afghan-led”. As one commentator put it, launching and owning a peace process seems to be the only achievement that can ensure his political survival and potential re-election sometime in 2019.

Pakistan is in the talks because its new Prime Minister Imran Khan is for peace and economic development and not war. China has teamed up with Pakistan to play a constructive role in Afghanistan as it needs peace to make a success of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in the Central Asian region. And Russia is interested in expanding its influence in Afghanistan to fill the gap when America withdraws. The Russian Foreign Minister, Sergei Lavrov, met a Taliban delegation recently.

Filling a gap

The other change in the situation is the poor record of the democratic governments led, in succession, by Presidents Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani. To their credit, both had opened up and liberated Afghans from the thralldom of Taliban’s harsh version of Islamic orthodoxy. But their administrations have become a byword for inefficiency and corruption. They have also not been effective in countering the Taliban militarily. In a country wracked by war, and saddled with weak institutions, the Taliban’s moralism and brute power to enforce edits appear to have an appeal.

The Taliban have been exploiting the developing situation to portray themselves as a more desirable alternative. In fact, the Taliban have shed some of their rigidity and have been co-opting some of the State and non-State institutions to administer the areas which they control or have partial power over.

Shadow State

In their paper in ‘Afghan Analysts Network’ entitled ‘One Land, Two Rules: Service delivery in insurgent-affected areas,’ Jelena Bjelica and Kate Clark say that the Taliban consider themselves as a “government in absentia”.

Since 2003, the Taliban have been, with varying degrees of commitment and effectiveness, trying to deliver services normally associated with a State and to develop ‘civilian’ structures of  governance.

governance.

Right from the beginning of the insurgency in the 1980s, the Taliban have been having courts of their own to deliver justice. After 2001, whenever Taliban insurgents moved into an area, they prioritised the setting up alternatives to the state’s judicial system. Because of the corruption and inefficiency in the government’s judicial system, the Taliban’s courts were popular and became one of the insurgency’s main strengths, Bjelica and Clark say.

However, the Taliban have found it virtually impossible to accept the modern secular educational system. In 2006, they issued their first Layha or Code of Conduct. While the Code allowed education, it could be given only in a mosque or similar Islamic institution with the course content being highly Islamic. Schools which did not follow this diktat would be closed or burned. Any contract of an educational institution with an NGO, in exchange for money or educational material, had to be authorised by the Taliban at the highest level.

In 2008-2009, provision of State-like services with accountability were introduced. “The Taliban set up a more responsive complaints system, whereby, inhabitants of rural areas could request investigations even into corrupt Taliban commanders or members. Two new committees, one to handle complaints from commanders and fighters, and another to deal with villagers’ grievances, were set up in 2008,” Bjelica and Clark point out.

The Codes introduced in 2009 and 2010 set up policy and administrative commissions for various subjects such as Health, Education, Companies and NGOs.

By 2010, the Taliban changed their attitude to education. In 2009, the order to attack schools and teachers was removed from the Code of Conduct. The Taliban started engaging with the Ministry of Education, which had also decided to re-start negotiations with the Taliban. But the Taliban force changes in the school curriculum and are involved in hiring and firing teachers.

Bjelica and Clark point out say that the Taliban are more likely to support education if they get control over the curriculum, distribution of government funds, teacher hiring and placement, monitoring of attendance and performance and health and security arrangements at and around maktabs (ornon-religious schools). Varying arrangements are possible through negotiations, they say.

The Taliban never objected to the delivery of health services because they saw health delivery as less “political” than education. To show that they can do development work too, the Taliban have been posting videos showing their cadres involved in constructing roads and other infrastructure.

Co-option of Government structures

Bjelica and Clark observe that the Taliban’s sectoral commissions do not themselves provide services, but co-opt services rendered by the legitimate Government. They also co-opts NGOs and private companies and control them.

The Taliban indulge in taxation as well as extortion. Media outlets, businessmen, truckers, and even Provincial Council members and other officials, are taxed. They had begun to tax mobile networks after Government boasted that it had earned $ 1.4 million by increasing tax on them by 10%. But the Taliban boast that by maintaining tight security they allow businesses to operate safely.

The Taliban are exploiting Governmental corruption to present themselves as a contrasting outfit. Stinging reports of the Independent Joint Anti-Corruption Monitoring and Evaluation Committee’s (MEC) add grist to the Taliban’s mill.