Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Tuesday, 22 August 2017 00:38 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is reported that the Government will unveil a three-year development program on 4 September to coincide with the second anniversary of the formation of the National Unity Government. The next budget would be formulated in keeping with this program. This would be a three-year program to be implemented within a frame of eight years.

It is reported that the Government will unveil a three-year development program on 4 September to coincide with the second anniversary of the formation of the National Unity Government. The next budget would be formulated in keeping with this program. This would be a three-year program to be implemented within a frame of eight years.

This is extremely good news. The Sri Lankan economy is drifting like a ship without a rudder. It could hit the rocks very soon, drowning all of us, except the commission earners, unless it is manoeuvred properly by employing the best principles and techniques of national planning.

The people are, however, very sceptical of plans. They have been treated to development visions, Chinthanas, strategies and plans, which became obsolete even before the ink ran dry. The only saving grace is that the proposed exercise is to be steered by Eran Wickramaratne for whom there is very high regard among professionals.

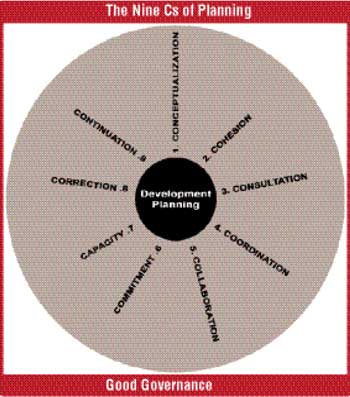

The nine Cs

For the planning exercise to be successful it must be based on certain concepts and principles. I wish to share briefly the concepts and principles I have identified for the purpose of engaging MPA students, at the PIM, in interactive learning exercises on development planning. The Nine Cs diagram is reproduced on this page. It was developed to provide mental hooks for students to remember the most important features of good planning. They are by no means exhaustive and readers are invited to add value with their comments.

1. Conceptualisation – forming a clear picture of the current situation and where one would like the country to reach within a feasible period of time. There must be quantitative targets, employing, as far as possible, key performance indicators.

2. Cohesion – this reflects a clear appreciation of the inter-sectoral and intra-sectoral ramifications of policies and programs. There are symbiotic relationships within and among sectors that must be taken into account in a national planning exercise.

3. Consultation – there must be a clear understanding among all, at least the principal, stakeholders about the implications of policies and the role each could play in making them effective.

4. Coordination – this follows 3 above. Coordination is an imperative for success, in particular within government.

5. Collaboration – follows 4 above where stakeholders decide to take responsibilities. Collaboration is required not only within Government but also between Government agencies and the private sector.

6. Commitment – very often projects and programs fall off due to lack of commitment on the part of stakeholder Government agencies to implement them. This is often caused by myopic political considerations.

7. Capacity – this refers to the technical and managerial ability of public servants which must be taken into account when formulating projects. Where such capacity is lacking the projects must contain provision to build the required levels of competence.

8. Correction – even the best technically crafted plans need revision due to vicissitudes of the global economy as well as domestic contingencies. This is why most countries and Sri Lanka in the past used ‘rolling plan techniques’. The five-year Public Investment Program of the National Planning Department was prepared in the past on this basis.

9. Continuation – there is a tendency to abandon plans half way through due to political or administrative changes with severe economic and, often, social consequences.

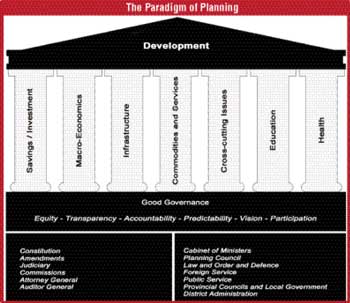

The Greek temple indicates how the objective of development at the top is to be reached through the seven pillars of intra-sectoral and inter-sectoral coordination by applying the 9 Cs, firmly based on the principles and institutions of good governance.

Bridging the savings/investment gap

The biggest challenge is how to bridge the savings/investment gap. We could resort to external borrowing or invite FDI (Foreign Direct Investment). In both cases there must be strong cost benefit analysis, including environment impact assessment, before we decide to use them. In the case of loans, in particular, we have to ensure that the envisaged development activity will yield sufficient income for pay back. We have to avoid Mattala and Hambantota Port fiascos.

The macroeconomic pillar represents fiscal, monetary and balance of payment areas. The problems confronting fiscal policy are well known. We have to not only raise revenue but also ensure that it is equitable. The Prime Minister recognised the problem in his October 2015 speech. He said we need to reduce indirect tax revenue from 80% to 60% gradually. Yet in the Budget that was presented soon after, one month later, the Finance Ministry thought it fit to raise it further.

Where monetary policy is concerned we can be happy that the Central Bank is currently on the right track, particularly in managing the interest rate regime. It’s greatest challenge, however, is to deal with the exchange rate. Is it going to stifle it under political pressure to protect the domestic consumer or allow it to find its mark to discourage imports and encourage exports? The best way to protect the consumer is to promote domestic production, particularly in agriculture.

Infrastructure development

Infrastructure development needs heavy long-term investment. This is where we need to look out for external sources.

One major issue with regard to large scale infrastructure projects is the shortage of semi-skilled and skilled labour. We have to avoid as far as possible too much reliance on imported labour. This is too large a problem to be dealt with piecemeal and in an ad hoc manner. It is only a well-crafted human resource development strategy and a plan that could address this problem effectively.

Unfortunately, all skills development programs so far seem to reflect piecemeal approaches, uncoordinated with sectoral development programmes, which is partly due to the lack of a medium to long term national plan.

Commodity production

Commodity production covers basically areas that come under agriculture and manufacturing. More than 70% (international calculations say 86%) of the population live in rural areas. The need to raise agricultural productivity is a long recognised need.

Academics, researchers as well as public servants and businessmen have been talking about the benefits of a consolidated agricultural development drive, to raise both domestic consumption and export earnings. It has been estimated that nearly 35% of agricultural production is wasted through post-harvest losses. There have been numerous agricultural plans, but with little impact mainly due to lack of proper planning and implementation. The need of the hour is an integrated plan for agriculture and rural development, which, in short should take into account the 9Cs identified earlier.

Where the manufacturing sector is concerned, the country has to move away from traditional industries. We have to look for areas where Sri Lanka has the potential to develop internationally competitive products.

Good governance platform

In short, the way forward, in the present global context, is to look for international supply chain opportunities. This is where FDI could be productive. The Government, in association with the various business chambers, should explore opportunities and make provision to exploit them.

Cross-cutting issues relate to poverty, gender and environment concerns which are embedded in all sectors of the economy and need a consolidated approach. Education and health issues also have a bearing on these issues. Yet again, there are numerous plans to address these issues, what is lacking is the 9Cs approach. All the above conditions for successful planning can be fulfilled only on the platform of good governance. This is provided by the legal framework and the institutional structure. The available space does not permit an elaborate description. There is, however, one condition that needs stressing; that is, predictability. Uncertainty is caused by the Government’s habit of changing policy goal posts when the match is in progress. Rule of law must prevail to give confidence to investors.

The Hambantota imbroglio has done nothing good to provide such confidence. It is a reflection of the Government’s vulnerability to myopic political pressure. Of course, the Government too should take some responsibility due to lack of transparency and effective communication.

Good institutional framework

No matter how good the legal framework is, good governance cannot prevail without a good institutional framework. The Cabinet at the helm of policymaking and implementation must be of a manageable size and structure. The deficiencies in this regard in the present context are well known and needs no elaboration. But even the best of cabinets cannot deal effectively with the loads of proposals that are presented for approval. This is where cabinet sub-committees become useful.

Where development policy issues are concerned, the cabinet sub-committee (CCEM) needs technical advice. It needs the support of a body of professional advisors drawn from the administrative services, the business community and academia. This is the role that could be played by a National Planning (or Economic) Council.

However, even the best of cabinet structures and planning councils could do little, if there isn’t a solid foundation of a public administrative system that is both competent and motivated. The government, judging from the comments made by ministers themselves, our public administration system is almost moribund and archaic, unable to meet contemporary development challenges. The Government approach, in this regard, however, has been piecemeal and almost complete reliance on foreign consultancy services and short-term study tours, reflecting a lack of imagination on the part of our policymakers.

About piecemeal approaches, this is what Shelton Wanasinghe said in his monumental report (a prediction) published in 1987: “The committee does not consider that it is possible to implement bits and pieces of the proposed agenda and to expect to improve effectiveness. Actually, the implementation of bits and pieces of the suggested agenda could be dangerous in that it would lead to incoherent and chaotic results which would put the administrative system back rather than propel it forward.”

[Dr. Lloyd Fernando (Msc, Moscow, D Phil, Sussex) was in charge of the National Planning Department for 11 years before he joined the Board of Directors of the Asian Development Bank in Manila. On his return he held the position of Chairman of the Marga Institute. Currently, he is attached to the Postgraduate Institute of Management and is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Gamani Corea Foundation.]