Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Wednesday, 24 April 2024 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

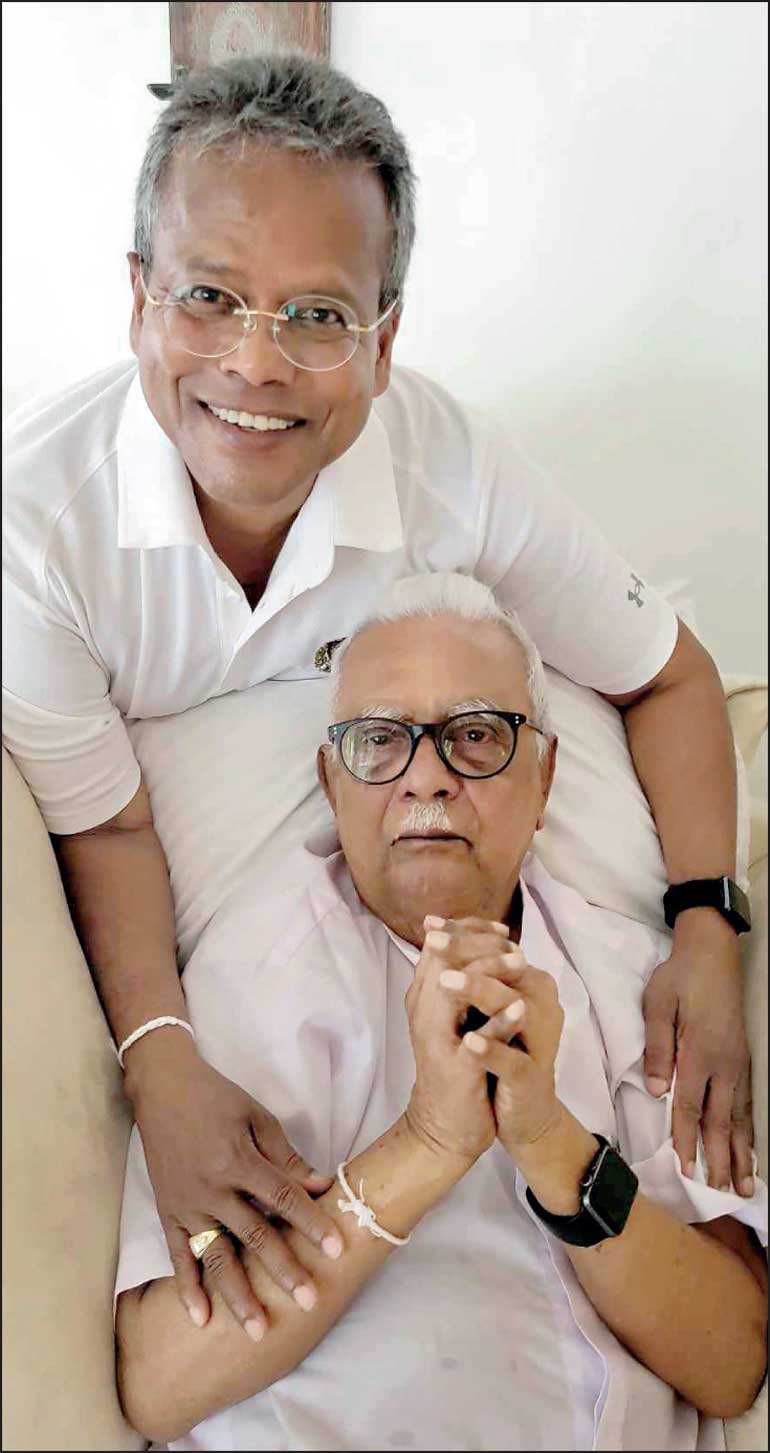

Celebrating Ari Aiya’s 92nd birthday

(KRAKOW, Poland): On the morning of 16 April, Dr. A.T. Ariyaratne’s family informed me that he was in critical condition. In the quiet of the evening, I was heartbroken to learn that “Ari Aiya” of Sarvodaya—as I affectionately called him for more than half a century—departed us peacefully.

(KRAKOW, Poland): On the morning of 16 April, Dr. A.T. Ariyaratne’s family informed me that he was in critical condition. In the quiet of the evening, I was heartbroken to learn that “Ari Aiya” of Sarvodaya—as I affectionately called him for more than half a century—departed us peacefully.

With a clear and sharp mind until his last breath, the 92-year-old soul lived for others with his quintessentially Buddhist way of life as a compassionate servant-leader. Undeniably, Ari Aiya drew equal inspiration from the Gandhian philosophy of non-violence. When he received the Hubert H. Humphrey International Humanitarian Award from the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs in 1994, I hailed him as the “Gandhi of Sri Lanka.”

Ari Aiya was a mentor, a friend, and a guiding figure in my formative years in Sri Lanka. We will all surely miss this remarkable human being; however, his message of “the awakening of individual personality for human progress” remains a living legacy for posterity. Former Secretary of State Mark Ritchie of Minnesota, a mutual friend, reminded me that “humanity is less kind and less peaceful today with this loss—more for the rest of us to do.”

Indeed, the visionary founder of the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement lived a peaceful life of simplicity that has been a source of inspiration for many. For him, Sarvodaya meant “awakening of all” through Shramadana: the voluntary “gift of labour” for the common good—seeking to uplift the lives of outcaste villagers. The post-independent nation was, and still is, a land of 15,000 marginalised villages. It represents about 80% of the island’s population, a group perennially ignored by the former masters of the colonial plantation economy.

Simple but powerful idea

While teaching at Nalanda College in Colombo, Ari Aiya inspired a dedicated group of 40 students and 12 teachers for an “educational experiment” focused on social change in 1958. This novelty endeavour laid the foundation for Sarvodaya, a social movement that quickly gained widespread popularity throughout the island.

Ari Aiya was a fervent believer in the Buddhist and Gandhian principles of non-violence; however, he embraced all religious and cultural values in his evolving multilingual, multiracial, and multireligious society of Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, Christians, and others. His secularised Sarvodaya teachings integrated these elements into a unifying force aimed at achieving ultimate liberation (Vimukthi in Buddhism). This was realised through villagers making collective decisions at “family gatherings.”

Employing the Buddhist analysis of human suffering (Dukkha), Ari Aiya applied the secular principles of Shramadana. This path aimed for a progression from the individual awakening of personality (Purusodaya) to the awakening of the village (Gramodaya), the country (Deshodaya), and ultimately the world (Vishyodaya). His philosophy emphasised personal transformation as the starting point for uplifting each villager from poverty and achieving welfare for all.

Awakening

In her handbook for humanitarians and development practitioners, ‘Stone Soup for the World: Life-Changing Stories of Everyday Heroes’, Marianne Larned profiled the legendary Dr. A.T. Ariyaratne as an ordinary person with an extraordinary vision, conviction, and innovation. I was honoured to contribute to the chapter on “Awakening,” where I shared my first encounter with Ari Aiya and my experience of a Sarvodaya Shramadana “family gathering” in Polonnaruwa—my birthplace and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

For me, the essence of Shramadana was the realisation that volunteering and the “gift of labour” deepen our understanding of interdependence and the impermanence of our life. Through the underlying conviction that “we build the road, and the road builds us,” this awakening emphasised the reciprocal nature of contributing to human progress.

This practicum had a lasting impact, influencing me beyond my formative years in Sri Lanka. Even while studying and working in the United States, I maintained contact with Ari Aiya and Sarvodaya. When the University of Minnesota published my manuscript, ‘The Political Economy of Poverty Alleviation in Developing Countries’ (1992), Prof. Vernon Ruttan—a father of the Green Revolution—highlighted the development paradox in Sri Lanka: despite having high life expectancy and literacy rates similar to Japan and South Korea, Sri Lanka’s GDP per capita income was relatively low. This paradox also puzzled Nobel Laureate economist Amartya Sen.

When I explained to Prof. Ruttan that Sarvodaya and Buddhism might offer an explanation for Sri Lanka’s development paradox, he was intrigued. Emphasising the Buddhist values of education and health as essential for liberation from suffering, I suggested they fostered a focus on well-being within Sri Lankan culture. Fascinated by this connection, Prof. Ruttan visited Ari Aiya in Sri Lanka to study Sarvodaya in its village context. Subsequently, I engaged in a series of enlightening conversations with Prof. Ruttan and Ari Aiya.

These conversations and explorations culminated in the University of Minnesota publishing my next book, ‘Buddhist Equilibrium: The Theory of Middle Path for Sustainable Development’ (1993). Following its publication, Ari Aiya later incorporated this framework in his “Schumacher Lectures on Buddhist Economics.” Interestingly, two decades earlier, the Sarvodaya model for holistic human development had also influenced British economist E.F. Schumacher’s seminal work, ‘Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as If People Mattered’ (1973). Sarvodaya’s focus on people-centred development—accentuating a path from personal awakening to national progress—predated the emphasis on similar concepts found in the UN Human Development Report and the World Happiness Report.

Nonetheless, Ari Aiya was globally known as a visionary leader who uplifted the rural poor. He is Sri Lanka’s most decorated citizen with over 100 international prizes that recognised his holistic development model, which highlights individual personality-awakening as a solution for human progress at large. His tributes included the Magsaysay Award (also known as the Nobel Prize of Asia) of the Philippines, the King Beaudoin Award of Belgium, the Niwano Peace Prize of Japan, the Gandhi Peace Prize of India, and the Humphrey International Humanitarian Award of the United States.

Awakening for progress

Ari Aiya’s influence and his Sarvodaya teachings extended far beyond the island-nation. For example, soon after the tragic 2004 tsunami, the United States channelled much of its humanitarian assistance through the Sarvodaya network of village centres. When the United States Senate Majority Leader Dr. Bill Frist and Secretary of State Gen. Colin Powell visited Sri Lanka, they were impressed by the rapid transformation of these centres into effective tsunami relief hubs. Witnessing Sarvodaya’s democratic “family gathering” model and overall operational efficiency, the senator met Ari Aiya, the “little, big man,” and later described him as the “holy man” of Sri Lanka.

In her tribute to Ari Aiya upon his passing, United States Ambassador Julie Chung expressed the gratitude of the American people for Sarvodaya’s enduring partnership. She recognised that Ari Aiya’s Sarvodaya work helped “to uplift the lives of countless Sri Lankans” and continues to “inspire generations to come.”

With remarkable foresight, Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike predicted the success of Ari Aiya’s inaugural 1958 educational experiment in Kanatholuwa, the birthplace of Sarvodaya. The prime minister entrusted his wife Sirimavo Bandaranaike with delivering a letter to Ari Aiya. In it, he commended the Sarvodaya pioneer for uniting Nalanda College student and faculty volunteers to work alongside marginalised villagers in a shared effort towards upliftment.

Building on previous examples of success, perhaps successive governments should have fully embraced Sarvodaya to address Sri Lanka’s economic, social, moral, and spiritual challenges. Through the Sarvodaya philosophy, Ari Aiya has shown us the pivotal notion that the individual “awakening of personality” must precede broader societal change or the “awakening of others.” Thus, this reflects the immutable natural laws of our interdependence and impermanence that shape our individual and collective Samsaric journey both within this world and beyond.

(The writer, an alumnus of the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs, is a presidential advisor to the US National Security Education Board and the inaugural Taiwan chair and distinguished visiting professor of international relations at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland.)